TWIN FALLS — In terms of geography and culture, Twin Falls can scarcely be farther removed from Afghanistan or Iran, Burma or Nepal.

Yet in schools such as Twin Falls’ Lincoln Elementary School, in a portable building abutting a blacktop playground, newly arrived refugee students begin their long and stark transition to American schools.

Yet in schools such as Twin Falls’ Lincoln Elementary School, in a portable building abutting a blacktop playground, newly arrived refugee students begin their long and stark transition to American schools.

Refugee resettlement is no longer an emotional yet faraway topic in Twin Falls. But that’s been true for a generation. The first refugee students began arriving in the mid-1980s, mostly from Southeast Asia. Nonetheless, in recent months, the city’s residents were asked to weigh that 30-year experience against a campaign that declared refugee resettlement a costly security risk.

Idaho’s refugee education programs are small and scattered. But now, more than ever, their future rests with a debate over national security and terrorism.

Refugee students, by the numbers

The State Department of Education does not have hard figures on refugee students. Districts aren’t required to determine whether students are refugees, and some registrars simply don’t ask.

“It’s really a touchy subject,” said Christina Nava, the department’s English learners and migrant director.

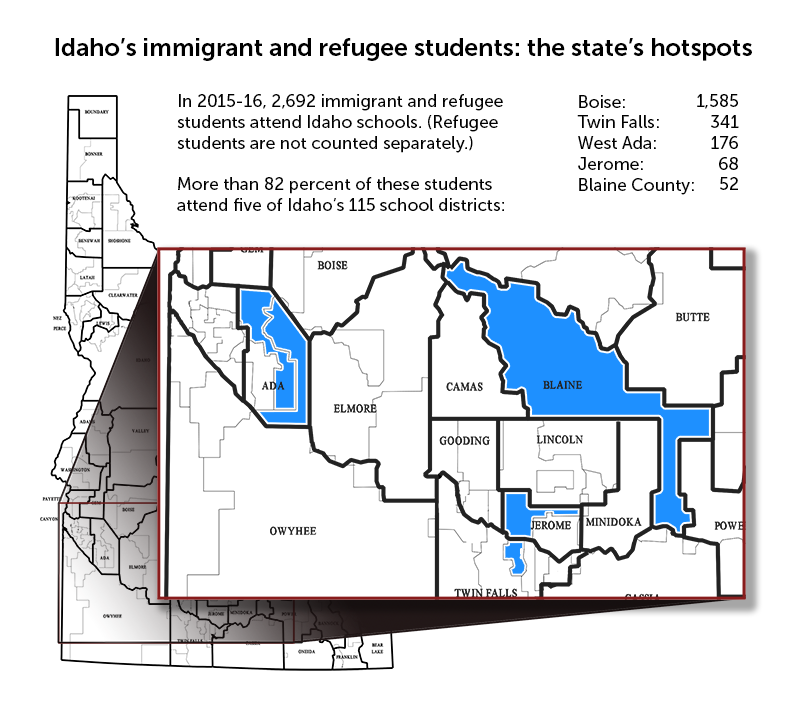

The state does track immigrant students, a group that includes but is not limited to refugees. In 2015-16, 2,692 immigrant students attended Idaho schools — slightly less than 1 percent of the state’s overall student enrollment.

It’s also unclear how Idaho immigrant and refugee students perform in school. The state is not required to report this data as part of its Title I “report card” to the federal government.

In Twin Falls, home to a thriving refugee student program for three decades, immigrant and refugees have graduated at a 93 percent rate over the past six years. By comparison, the district’s overall 2014-15 graduation rate was 80 percent, and the statewide graduation rate was 79 percent.

A national and local debate

The debate over refugee education has little to do with test scores or graduation rates, however. The debate instead centers on national and homeland security.

- Days after the Nov. 13 ISIS terrorist attacks in Paris, Gov. Butch Otter joined 29 of his colleagues in opposing a resettlement program for Syrian refugees. “I am duty-bound to do whatever I can to protect the people of Idaho from harm,” Otter wrote at the time. In Boise — the school district with Idaho’s largest immigrant student population — 23 of the district’s 1,019 refugee students come from Syria. None of Twin Falls’ refugees come from Syria.

- In March, U.S. Rep. Raul Labrador introduced a bill to cap the resettlement program at 60,000 refugees per year, and allow state and local governments to opt out of refugee resettlement programs. The bill, awaiting a House floor vote, does not address refugee education, Labrador spokesman Dan Popkey said.

- Local activists have been agitating for veto power over refugee resettlement, with little success. In Ada County, home to the Boise and West Ada school districts, county commissioners rejected a bid to add an advisory question on refugee policy to the May 17 primary ballot. “The Ada County commissioners do not have the authority to make changes on a national level,” Commissioner Jim Tibbs, a former Boise police chief, wrote in a letter to critics of the refugee resettlement program.

In Twin Falls, the local debate over refugee education has been pitched — and prolonged.

The Twin Falls debate

In Twin Falls, a city of about 45,000 residents in the heart of south-central Idaho’s agricultural belt, critics focused their attention on the Refugee Center at the College of Southern Idaho, with a petition drive aimed at closing the center.

Closing the refugee center wouldn’t necessarily bring an end to refugee resettlement in the area. Twin Falls has a sustained refugee network, and newcomers might still gravitate to the city on their own, said Khrista Buschhorn, an ELL instructional coach at Twin Falls’ Canyon Ridge High School. But without the refugee center, Twin Falls schools would lose the conduit that helps students make a smoother transition to a new home.

In 2015, the refugee center predicted an influx of 300 new arrivals — including some refugees from Syria. That news prompted a petition drive targeting the center, and some heated public hearings on the topic. At one point, 14-year state Rep. Pete Nielsen, R-Mountain Home, questioned why the CSI center was doing the “Muslim thing.”

In a debate dominated by concerns over security, the cost of refugee education also entered into the equation. Federal and state programs cover much of the costs, school district officials said, and at $249,000, the 2014-15 refugee education costs made up a mere sliver of the school district’s $45 million annual budget. Critics saw the numbers differently.

The Committee to End the CSI Refugee Center said on its website: “Every dollar in profit that a refugee center earns for trafficking refugees represents many dollars in external costs that (are) foisted upon Twin Falls County citizens, especially increased education and welfare costs.”

When the decision went to the people — in a conservative and reliably Republican community — the outcome wasn’t even close. Refugee center critics needed to collect 3,842 signatures to get their referendum on the May 17 ballot. When the April 4 deadline arrived, they had only 894 signatures, less than a fourth of their goal.

‘We stand poised’

While the failed petition drive unfolded around town — illustrative of a larger national debate — the Twin Falls district’s educators and administrators tried to stay focused on the task at hand. The job: educating 341 immigrant students, and integrating them into a district of more than 9,000 students.

“We have to be professional,“ district Superintendent Wiley Dobbs said. “We kind of have to separate ourselves from the discussion that’s going on in the national background.”

For the CEO of the city’s school district, however, that detached attitude goes only so far. Dobbs found himself attending some of those emotional public hearings about the refugee center — he came away sensitive to community fears about terrorism and extremism, but convinced federal and local authorities could properly vet new refugees. As refugee education costs became a point of contention, the district set out to put the numbers into perspective.

Educators are removed from the refugee resettlement controversy, and for one simple reason. It is a bedrock principle of the public school system to educate every student, regardless of academic background or country of origin.

So at the State Department of Education, across the street from Otter’s Statehouse offices, the department’s administrators have taken no position on Syrian resettlement policy.

“If they show up at the school district, they need to get the support that they deserve,” department spokesman Jeff Church said.

In Twin Falls, Dobbs says he has heard no word about whether Syrian refugees may come to the district. But usually, schools receive little or no advance word.

“We stand poised, ready to help any group,” he said.

Tackling the immigration topic

In November, the Twin Falls School District and the local chamber of commerce hosted a tour for local legislators. They toured the refugee classroom at Lincoln Elementary School. One lawmaker asked a student about going to school amidst the debate over refugee resettlement. The student said classmates didn’t talk about the issue. Only the grownups did.

“I think it was somewhat eye-opening to all the attendees,” said Twin Falls Mayor Shawn Barigar, the chamber’s chief executive officer.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to insulate refugee students from the refugee debate.

At Boise’s Hillside Junior High School, Jill Ball tries to shield her seventh- and eighth-grade students from the issue. But Ball — a lead teacher at Hillside’s Bridge Program, an intensive English immersion program for immigrant and refugee students — does discuss the issue with her ninth-graders.

In those ninth-grade classes, the topics are timely, and personal. When the presidential race comes up, Latino students bring up Republican candidate Donald Trump and his proposal to build a wall along the Mexican border. Refugee students might not understand why they are the subject of a national debate — but they are well aware that they are.

“I think I want them to know that it’s out there,” said Rita Hogan, a teacher in Hillside’s English language development program. “But they know.”

The Hillside teachers’ instincts are on the mark, said Julie Sugarman, a policy analyst with the Migration Policy Institute, a nonprofit Washington, D.C., think tank.

“It’s not like kids don’t know,” said Sugarman, who has 16 years’ experience working on issues facing English language learners. “It’s not like kids don’t hear.”

ELL education experts have been urging teachers to address immigration issues head-on, Sugarman said. And the divisive political debate provides a learning opportunity. “The kids have something to hook the conversation on.”

At Boise’s Borah High School — home to some 150 refugee and immigrant students — even the newest newcomer students are alongside students in the hallways, in the cafeteria and at physical education and elective classes. This is where the newcomers’ English skills begin to flourish, said Laura Boulton, a Borah math teacher who has about 90 immigrant and refugee students in her classes. As the groups interact, the native students get an education in global issues.

“We learn so much more about their culture and what they’ve gone through in their life to get here,” said Borah Principal Tim Standlee. “These kids have amazing stories about what they’ve had to overcome in their lives.”

The conversation isn’t always civil. In Twin Falls, refugee students are sometimes harassed when they are outside school, said Kimberly Allen, an instructional coach at Twin Falls’ Canyon Ridge High School. As a result, it is incumbent upon teachers to create a comfortable setting for students who have fled from an unsafe and unstructured homeland.

“This has just remained a safe environment,” she said.

This series at a glance

Day One: Refugee programs become embroiled in a national debate

Day One: In Boise’s Bridge Programs, immigrants learn to be students