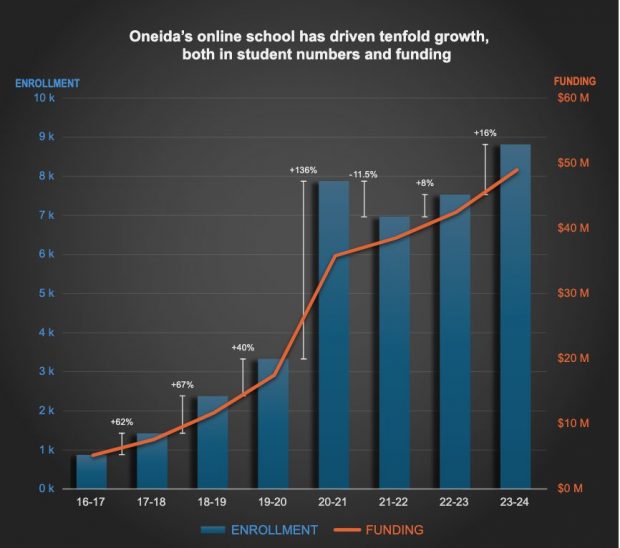

The Oneida School District’s enrollment — and funding — have increased tenfold in the past eight years. And so, too, have problems.

The rapid-fire growth has been fueled by the district’s adoption of an online school that enrolls students statewide. But systemic issues with the school’s special education program have accompanied that growth, according to an investigation report from the Idaho Department of Education. The district’s reputation is further clouded by its partnership with questionable for-profit businesses, and by records of troubling academic achievement.

It’s a mess that will take years to untangle.

Addressing Oneida’s vast special education shortcomings will require at least three to five years of ongoing state oversight, investigator Elaine Eberharter-Maki concluded in an April 2023 report obtained by Idaho EdNews through a public records request. One of the report’s main findings: Oneida school leaders routinely and inappropriately shifted their responsibility to appropriately educate students with disabilities to parents and/or other public school districts.

Students enrolled in Oneida’s online school, called the Idaho Home Learning Academy, get little if any direct instruction from teachers, whose primary roles seem to be grading online assignments. Rather, students complete online education programs overseen by private, for-profit companies — both of which have come under fire in other states for suspect practices. Students’ education is largely left up to parents, who become the general education teacher and the special education teacher — even when they lack the training or certification to do so.

Oneida Superintendent Jon Abrams said the district is working with the state to address concerns. He also defended the district’s deference to parents, and said IHLA’s explosive growth reflects their desire to have a say in their children’s education.

The state initiated the months-long investigation into the Malad-based district, an unusual move. Parent complaints normally spark investigations, as was the case in a recent report of systemic special education issues at Garden Valley School District.

Potential issues with the online school’s ability to provide special education services have been flagged as a concern since at least 2020, when current state superintendent Debbie Critchfield, then president of the State Board of Education, asked the IDE to take a closer look at the school.

The report is one of 37 issued statewide in 2023; in 35 cases, the district or charter in question was found out of compliance on one or more allegations. Oneida’s investigation stands out because it’s comprehensive, and illuminates a system of issues rather than an isolated incident.

Oneida’s online school is built on a partnership with two private education companies, both of which have come under fire in other states

Oneida School District is located in the rural Southeast Idaho town of Malad, with a population of about 2,300. More than three times that number — about 8,800 — attend its schools, and the vast majority are online students.

The district’s unprecedented student growth (up from about 880 in 2016) has led to an influx of cash to the district which now has a budget of about $49 million (up from just $5.2 million in 2016). Idaho’s school funding formula is complex and is tied to attendance, but in simple terms, the more students a district has, the more money it gets.

While online students have fueled Oneida’s financial growth, in-person students stand to reap a major benefit. The additional funding, paired with a $29 million bond passed last March, has helped fund a new elementary school at the district, according to The Idaho Enterprise, Oneida County’s local newspaper. The school will be built and ready in the fall.

Oneida’s online school started in 2016, when the district partnered with a for-profit online education company based in Utah, Harmony Education Services. The company has a checkered past, but remains as one of two district partners that oversee the online school.

Here’s what we know about Harmony Education Services:

- It was founded by Rob Muhlestein, a former Utah state senator and executive director of American Leadership Academy.

- Bonneville and West Ada contracted with the company in 2013. Both partnerships were short-lived before the districts cut ties with Harmony, and scaled back their online offerings to just local students, rather than statewide. Bonneville dropped the partnership partly due to difficulties serving special education students remotely.

- The company came under fire when a 2014 Utah state audit showed lax management of distance learning programs in two charter schools. Both schools severed ties with Harmony, and one local trustee called it a “predatory company.”

- In 2016-17, Harmony sought out Oneida School District to be a new host district, enrolling 200 students under the new partnership.

A second partner, Tech Trep Academy, has a similarly bruised reputation, and has been the subject of scrutiny in multiple states

In 2017-18, Oneida started partnering with a second Utah-based company called Tech Trep Academy, which partners with districts in a half dozen states. The private company has come under scrutiny in Indiana for “offering gifts or perks to parents in exchange for enrolling their students,” according to Chalkbeat.org, a nonprofit national news organization.

A Chalkbeat report on the virtual school — which offered parents cash, then points, to order items like textbooks, Netflix subscriptions, educational toys, and museum memberships — sparked Indiana legislators to pass a new law in 2022, strengthening bans on enrollment incentives.

At the Oneida School District, IHLA seems to have a similar system: Students get $1,700 each school year to spend on supplemental learning materials, which can include chicken coops, rabbit hutches, greenhouses, raised beds, kitchen supplies, digital pianos, filing cabinets, and more, according to the IDE report.

“An education through Tech Trep Academy is personalized and FREE,” the company’s website says on its FAQ page. “In addition, parents also receive access to a supplemental learning fund which can be used to select customized learning resources for their children.”

Tech Trep Academy runs an online school program in Utah called MyTechHigh. Multiple districts have cut ties, including Utah’s Tooele School District. Tooele dropped the program in January 2023, partly due to a lack of control over the curriculum, according to KUTV.com. In doing so, the district lost about 8,000 students — and $50 million, in a major budgetary blow.

Tooele leaders were not expecting the abrupt funding cut, which as of December was threatening construction progress on two new schools.

Tech Trep’s programs across various states were also the subject of an in-depth investigation by Texas TV Station KLTV.com.

The private companies recruit homeschool students, while downplaying that they are part of public school districts like Oneida

Together, Tech Trep and Harmony Education Services recruit students, mainly among homeschool populations.

In doing so, it seems the partners and district try to minimize the district’s status as a traditional public school to better attract homeschool parents, according to the state report.

The partners — not the district — provide parents with communications, curriculum choices and supplemental learning funds; oversee state testing support; and help parents with troubleshooting. The private partners also assign teachers email addresses associated with their companies, not Oneida School District, “as parents have been found to more positively respond (due to parents’ general preference of being aligned with “homeschooling” rather than being associated with the public school system), believing they are associated with the district through their chosen partner” rather than the other way around.

The district and partners have also contracted with six additional private institutions or programs so parents have more curriculum choices. Students can also choose curriculum from Edgenuity, Brigham Young University, or Idaho Digital Learning Alliance, though sometimes an extra fee is charged for those options.

A glimpse at Oneida’s disparate school systems and troubling academic achievement records

IHLA dwarfs Oneida’s in-person schools, with far more students and staffers. The two education systems have plenty of other differences, too — including a different academic calendar and different breaks — some of which have complicated efforts to provide special education services.

Oneida’s online and in-person schools by the numbers:

*Information is for the 22-23 school year.

| IHLA | Brick-and-mortar schools | |

| Grades served | K-12 | K-12 |

| General education teachers | 305 (most work part-time) | About 57* |

| Special education teachers | 19 (most work-full time) | 3 |

| Student enrollment | 7,218 | 959 |

| Number and percentage of students with disabilities | 423; about 6% | 52; about 5% |

| School days in a week | 5 | 4 |

| School days in a year | 165 | 148 |

| Breaks | Longer breaks at Thanksgiving and Christmas than the in-person schools, and two additional weeks off during the year. | Shorter/fewer breaks |

| Counties students hail from (out of 44 statewide) | 41 | 1 |

*This figure is an estimate based on the district’s total #of instructional FTE staff that year, which was 365

The differences extend to academic performance as well.

IHLA students are consistently behind their in-person and statewide peers on academic achievement measures

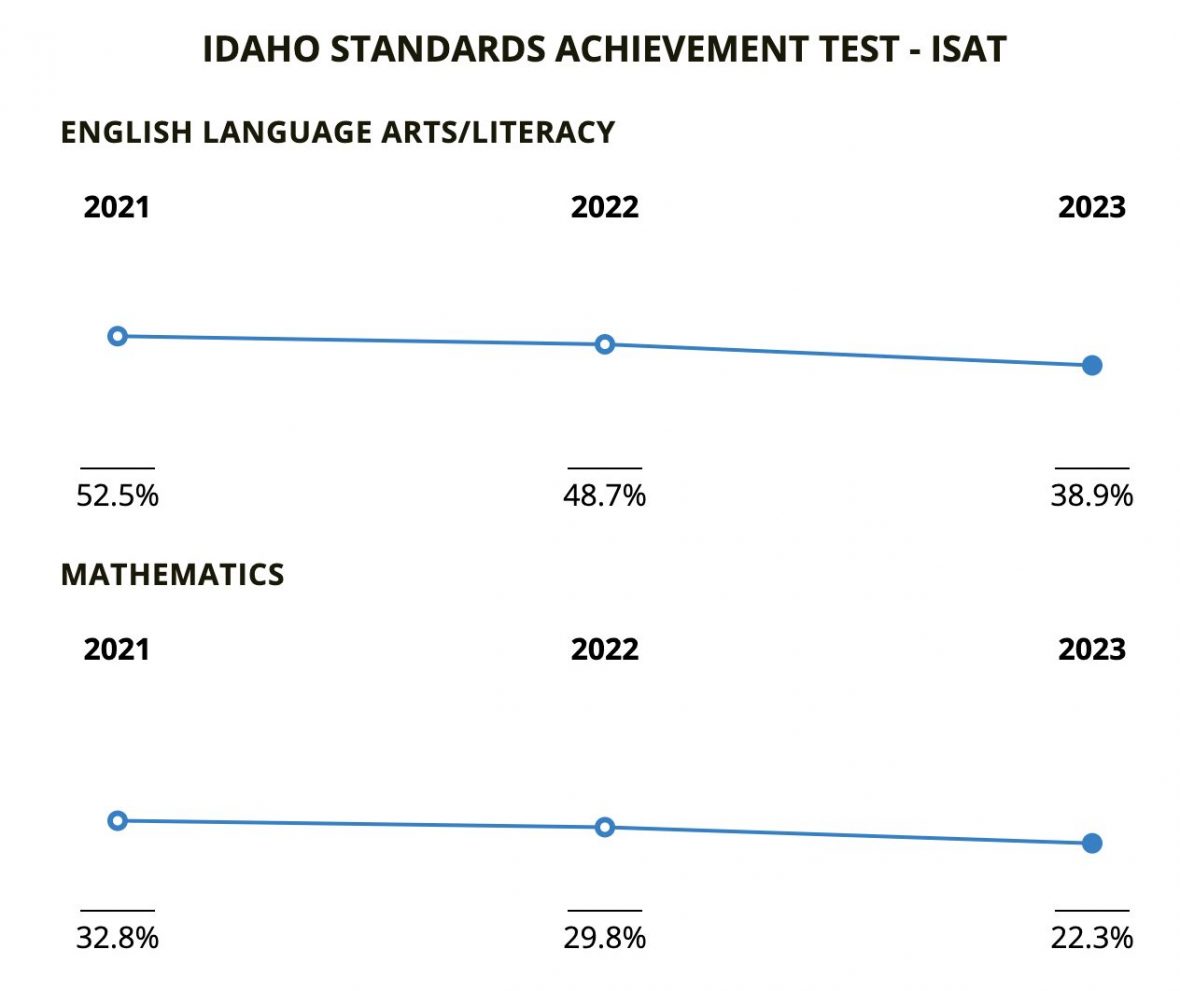

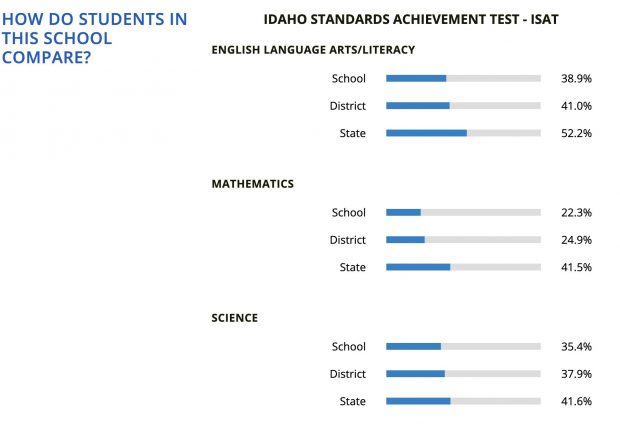

On the Idaho Standards Achievement Test, IHLA students were behind the district average on every measure, and significantly behind their peers statewide.

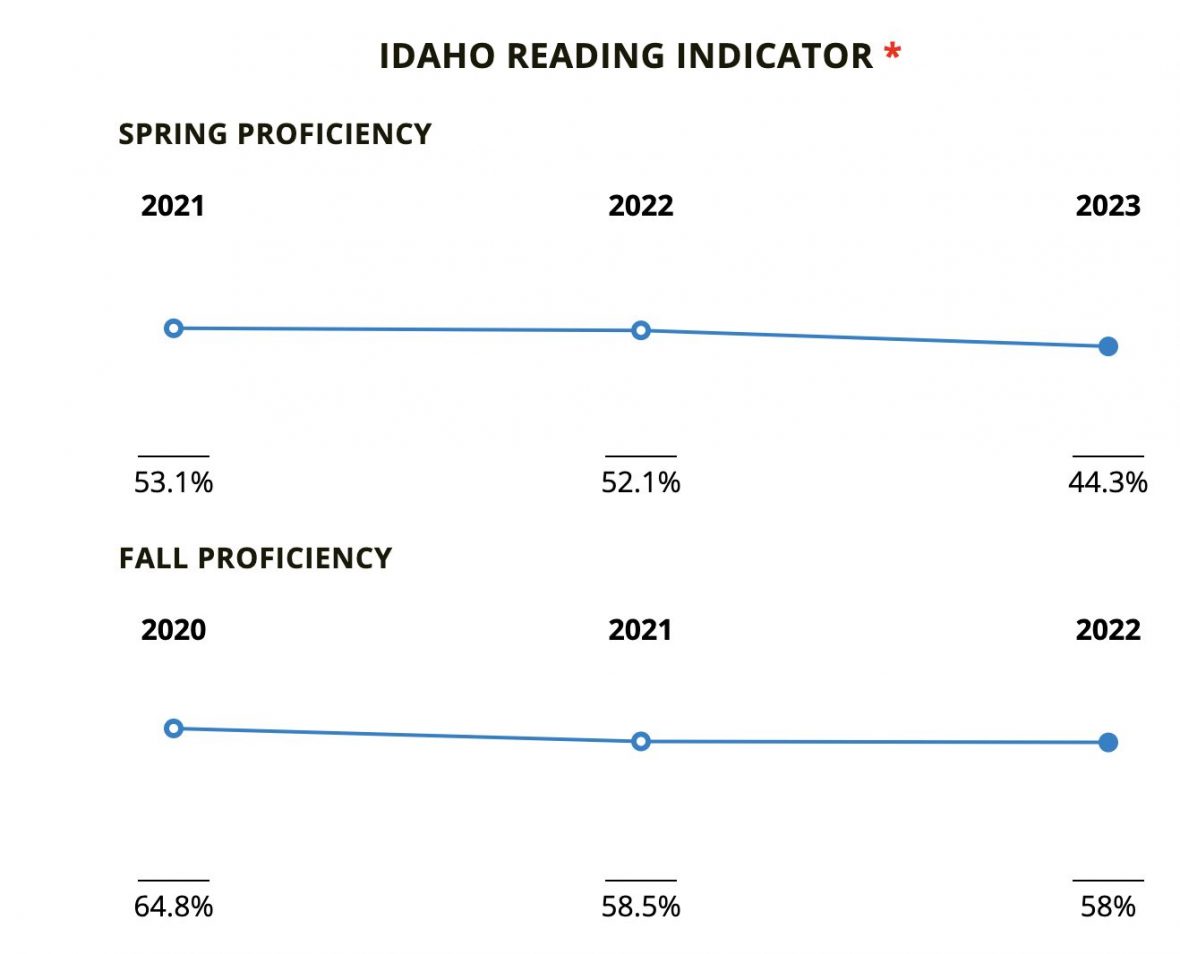

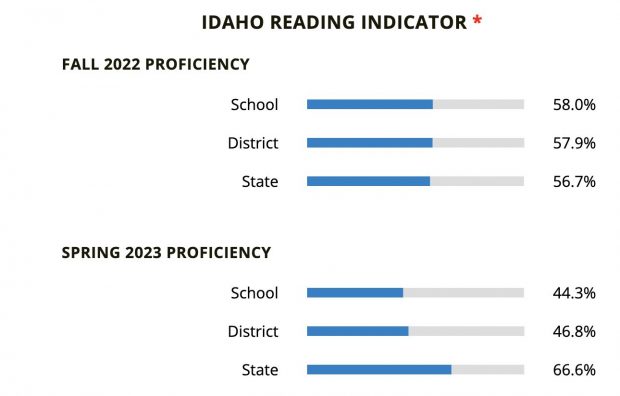

On the fall 2022 Idaho Reading Indicator, IHLA students were slightly ahead of averages at both the district and state level. But by the end of the year, their reading proficiency regressed by about 14 percentage points, putting them behind the district average and far behind statewide peers, whose reading proficiency grew by about 10 percentage points.

Proficiency levels for IHLA students on both academic measures have also decreased steadily over time.

The state investigation shows that the online students’ education was primarily left to parents to facilitate.

Oneida routinely shifted its responsibility to educate students with disabilities to parents

Parents of IHLA students in grades K-8 are expected to spend 20 to 30 hours each week acting as “learning coaches,” becoming the de facto teachers. Elementary students earn pass/fail grades and submit eight portfolios of their work each school year. In between portfolio submissions, parents submit learning logs, which consist of a few sentences outlining what their student has done the past few weeks. No work samples are needed.

At the high school level, parents are not expected to spend as much time facilitating their child’s education, and schoolwork is assessed weekly or more.

To track online attendance and seat time, students don’t have to log in daily. They are essentially considered present if their work gets done.

“Because students are instructed at home, parents have various ways to provide instruction, including other educational activities, such as participating in cooperatives or reading daily,” the report reads. “These minutes vary greatly from student to student in the files reviewed.”

Parents are also “the driving force” behind special education programs, even if it’s to their student’s detriment

When it comes to special education, Oneida school leaders inappropriately cave into parental demands, the investigation found.

“Parents are the driving force through the special education evaluation process,” the report reads. And, “staff defers to parent preference” when it comes to which areas of need the child will be assessed for. “The mandate to ‘consider’ parent input does not mean ‘acquiesce,’” the report reads.

Parent input is required in the process of determining whether a child is eligible for special education and what services are needed. However, trained district staff must ultimately make those decisions based on evidence and need.

Once an IEP is created, district leaders expect parents to implement it — and even take progress monitoring data — which are district responsibilities. And because all that takes place remotely, certified staff members “are not able to verify that instruction has been provided to the student regularly and with fidelity.”

Putting the burden on parents is not only inappropriate, it has resulted in students not receiving special education services, in violation of federal law, the investigation found.

IHLA’s special education program was ill-equipped to support students with disabilities

The report highlighted a number of issues with IHLA’s special education program, including:

Some parents enroll students in another public school district to get special education services that Oneida is not providing.

It is not legal for parents to enroll their students in two public school districts at the same time, but IHLA parents have done just that to get special education services that Oneida is not providing.

The report called out that practice, and again said the burden falls on Oneida’s shoulders — unless the student is only enrolled part-time at IHLA because they’re also enrolled in a private school or homeschool.

The district did not actively seek out children who might need special education services, as required by federal law.

The district neglected its duty to identify, locate, and evaluate potential special education candidates, a federally mandated responsibility called “Child Find.”

Oneida school leaders failed to complete student evaluations for special education candidates within 60 days, and sometimes avoided referring students to special education by providing them with interventions for up to 14 months.

Students who transferred into IHLA from other public school districts often “showed a significant decrease in special education” services.

That became evident after comparing the students’ transfer IEPs to the IEPs developed by the district. Staff said the reduction in services was usually due to students learning remotely, parent preference, or parents not obtaining services such as occupational or physical therapy.

IHLA doesn’t offer a way for special education students to be educated with non-disabled peers.

Federal law calls for students with disabilities to be educated with their non-disabled peers as much as possible. In a brick-and-mortar school, that would mean in the general classroom, as opposed to a resource room or other location.

But at IHLA, where everyone learns separately and at home, “there’s no spectrum of placements,” the investigator found. Instead, ”students are instructed in a restrictive home environment by their parents as the learning coach, are not interacting with non-disabled peers, and are being taught curriculum chosen by their parent.”

Many IHLA general education classes do not feature a virtual classroom, so that’s not necessarily an option either.

“The practice of staff deferring to parent choice in their decision to educate their children in the home setting as their learning coach is counter to (federal special education) requirements, effectively predetermines each student’s placement, and fails to provide for a continuum of placements, depending on student needs,” the investigator found.

IEP goals are not always appropriately updated.

IEPs are supposed to be updated when students meet goals. But that doesn’t always happen at IHLA, the investigator found. Some students met goals months before their IEPs were reassessed, and no actions were taken to amend the IEP in the meantime.

On the flip side, some IEP goals never got updated because the student made no progress toward them within the previous year — another red flag, as students should show some forward movement.

Staff were often unavailable, or lacked the appropriate training.

IHLA special education teachers were uncertain about their role in completing students’ special education eligibility reports, which were often incomplete.

Special education teachers were not consistently available for IHLA students, because they follow Oneida’s in-person calendar rather than the online calendar. That means there are about three weeks each year when they are unavailable to online students.

Further, some of the general education teachers appeared to believe that special education students did not need to be held accountable for meeting state standards once they were identified as having a disability and were provided an IEP.

Addressing IHLA’s special education deficiencies will require years of ongoing state oversight

The state laid out a seven-step corrective action plan for the district to follow. Notably, the required fixes are so “extensive” that state officials expect that ongoing oversight will be necessary for at least three to five years.

That’s especially prolonged, even when compared to a similar state investigation into systemic issues at the Garden Valley district. In that case, issues were expected to be addressed within a year.

The plan requires the district to:

- Provide and document extensive and ongoing staff training.

- Adopt the state-provided IEP platform, EdPlan.

- Communicate with parents in a way that makes clear that district staffers are employed by Oneida, not a private company. Notify the private partners that Oneida will create and provide all communications with parents about IHLA.

- Find out which students with disabilities are enrolled in another public school district; notify that district that it is Oneida’s responsibility to provide special education.

- Present curriculum created by various partners for the school board’s approval.

- Communicate with the public, via the district’s website, about its federally mandated special education responsibilities and requirements.

- Ensure all students with disabilities are receiving direct instruction, by certified staff, in the general education curriculum.

- Ensure all components of each student’s IEP, including accommodations and supplementary aids and services, are implemented by certified general and special education teachers.

The state said it would designate a special education director and school psychologist to oversee and assist the district as it makes the changes. Both staffers would not be Oneida employees, but the district must fund them.

Abrams, Oneida’s superintendent, said the district is working with the state to address the concerns, but declined to give further details regarding progress that’s been made since the report was issued nearly a year ago.

When asked about the weight given to parental preference when it comes to special education, an issue the investigator pointed out multiple times, Abrams defended the practice.

He said parents can opt out of special education services they don’t want, and the district provides the services they opt in for.

“That’s a choice … we partner with parents to provide the education they feel is important for their children to have,” Abrams said.

The systemic investigation was one of three that focused on the district last year. The other two, sparked by parent complaints, uncovered a combined nine violations pertaining to inadequacies with special education eligibility evaluations and an ineffective IEP.

Check out Idaho EdNews’ past coverage of IHLA:

Aug. 17, 2021: Unfamiliar territory: Wyoming educator learns to lead Idaho’s largest online school

Nov. 12, 2020: State education leaders want to know more about Oneida’s explosive growth

Nov. 5, 2020: Online school posts unprecedented enrollment growth, again

Jan. 14, 2020: Low-performing online school posts unprecedented enrollment growth, again

March 5, 2019: Online learning fuels Oneida’s continued, massive growth

Oct. 26, 2017: Oneida’s unorthodox digital partnership impacts millions of dollars and hundreds of students

EdNews Data Analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.