Across Idaho, parents of students with disabilities are frustrated.

They’ve repeatedly reported feeling unheard or misled in discussions with school leaders about their children’s needs.

Last year, dozens of them filed formal complaints with the Idaho Department of Education — a seeming last resort to advocate for their children. In many cases, districts took no action to remedy issues until the state investigated.

Under a federal special education law, parents must be given the opportunity to participate meaningfully in meetings and conversations where decisions are being made about their children’s education. And school officials should consider that input along with other sources of information, such as assessment data, evaluations, and teacher observations.

But in districts and charters across Idaho, that’s not always happening.

In 2023, the state completed investigations stemming from 37 grievances, mostly filed by parents or “complainants” about allegedly inadequate special education services; in 35 of those cases, investigators found that districts or charters were violating federal law. All told, 25 different districts and charters were not completely fulfilling their obligations toward all children with disabilities.

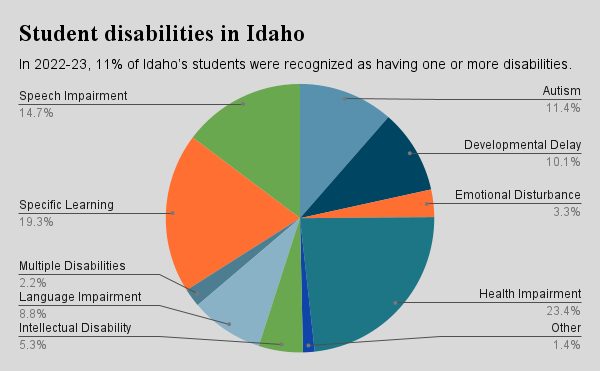

In 2022-23, about 11% of Idaho’s students were identified as having a disability. The percentage could be higher because a federal investigation last fall found that Idaho’s criteria for providing students with specific learning disability (SLD) services represent “a higher bar” than what is allowed. Because of that, students with learning disabilities like dyslexia were repeatedly denied services for years, Robin Zikmund, founder of Decoding Dyslexia Idaho told EdNews in January.

Among Idaho students who are recognized as having a disability, 23% have what’s vaguely referred to as a “health impairment,” which could mean a number of disabilities, including asthma, ADD or ADHD, or Tourette syndrome. Another 19% have specific learning disability, a category that includes dyslexia or a brain injury. About 15% have a speech impairment, and nearly 11.4% have autism.

Even when students are correctly identified as having a disability, dozens are not getting the services they need, according to state investigation reports from 2023 that EdNews obtained via public records request. More than 400 pages of documents shed light on how schools have foundered their federal responsibility to appropriately educate students with disabilities, a failure pockmarked with a frequent disregard for parents’ concerns, requests, and opinions.

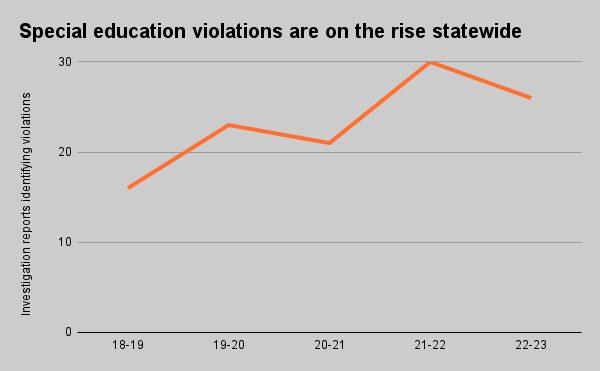

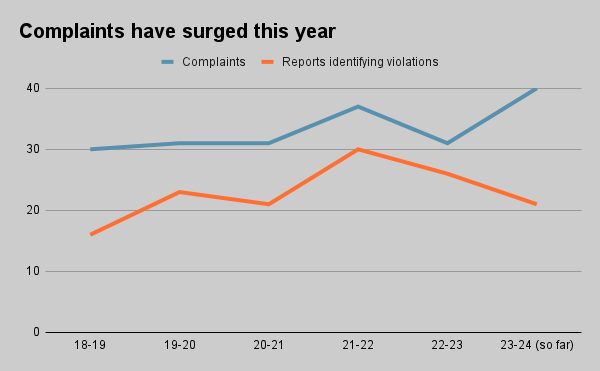

Violations have been on the rise since the 2019-20 school year, when the pandemic shuttered schools, according to state data. That year, investigation reports identifying violations jumped from 16 cases to 23. Since then — from 2019 to 2023 — there have been an average of 25 findings of noncompliance each school year.

Comparatively, complaints from parents or other parties have held steady — until this school year. With more than two months left until summer break (at most schools), more complaints have been filed than anytime in the past five years.

Among the dozens of investigations conducted in the 2023 calendar year, some districts or charters stood out due to the systemic nature of their violations, or for a high number of violations:

- Oneida School District, where an online school with rampant growth has systemic special education issues so entrenched that state oversight will be necessary for years to come. State investigators uncovered 15 violations last year, stemming from three investigations. In the systemic case, the district was an outlier for acquiescing too much to parents — rather than too little.

- Garden Valley School District, where high-profile special education violations have led to a full-scale investigation that found systemic issues at the district. State investigators uncovered 11 violations last year, after receiving two separate complaints.

- Elevate Academy Network, where two new schools failed to provide adequate special education. State investigators uncovered 24 violations last year, after receiving four separate complaints.

But their stories are just a fraction of the issues statewide.

Four Idaho districts had a half dozen violations or more, and others stood out for the nature of their violations — like teachers changing students’ grades from failing to passing, or leaving aides to manage a classroom.

The IDE has demanded all the districts and charters in question to improve their special education services. Compelled by the state, districts are either in the process of training staff and implementing better policies and procedures, or have completed required changes.

SHARE YOUR STORY If you’re the parent or guardian of a student with disabilities and have concerns about your school’s special education program, let us know. We’d love to hear your story as we continue coverage of special education in Idaho. Email Reporter Carly Flandro at [email protected]. You can also call or text her at (208) 317-4287.

The IDE only initiated one of the investigations — looking into systemic issues at Oneida. Grievances from parents or “complainants” sparked the other cases, which means there could be violations at other districts and charters that have not been investigated.

Below, we take a look at what went wrong in a half dozen districts where students’ special education rights were not upheld.

For a full list of school districts and charters the state investigated in 2023, and the number of violations and complaints, go here.

Before diving in, here are some terms you should know

Child Find According to federal and state law, districts are required “to locate, identify, and evaluate students suspected of having disabilities” for those aged three through 21. The onus is on the district, not the parent. This practice is called Child Find. Source: IDE.

Least Restrictive Environment (LRE) Under federal law, students with disabilities must be educated with students who are not disabled, to the maximum extent possible. Special classes, separate schooling, or other removal of children with disabilities from the regular classroom should occur only if the student cannot learn satisfactorily in a regular classroom, even with the use of supplementary aids and services. Source: IDE.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) This federal law makes available a free appropriate public education (FAPE) to eligible children with disabilities throughout the nation and ensures special education and related services to those children. Source: U.S. Department of Education

Individualized Education Program (IEP) An annual written record of an eligible individual’s special education and related services, describing the unique educational needs of the student and the manner in which those educational needs will be met. Source: IDE

Helpful Resource: Check out the Idaho IEP Guidance Handbook, created by the Idaho Special Education Support & Technical Assistance.

Investigations into four districts identified unqualified staff, ignored parents, and students going without services

Four districts logged a half dozen violations or more. In each case, the state has mandated remedies like staff training, providing makeup services students may have missed, and implementing improved procedures. Generally, school leaders are required to make the fixes within a few months to a year, depending on the severity of the issues. Rarely do the issues necessitate more than a year to address, as is the case in Oneida School District.

Here’s a look at what investigators found.

Investigators looked into three complaints and identified seven violations. The issues they described in their report included:

A “lack of qualified professionals:”

- Staff “lacked familiarity with and an understanding of” the term ‘Child Find’ and the district’s related responsibilities.

- Staff expressed confusion about the purpose of an initial referral meeting.

- Team members demonstrated a “lack of knowledge” about a number of other federal special education requirements.

Unilateral, uninformed decision: The district made a “unilateral decision” regarding whether a student had disabilities without sufficient information, and “failed to consider the complainant’s concerns.”

Dozens of students not provided required services: On one or more days, 38 of 44 students were not provided one-to-one services required by their IEPs. And 21 students missed 27 days of one-to-one services.

IEPs changed without a meeting: Of 44 student files reviewed, several contained IEPs that were changed without an IEP team meeting, which is a federal requirement.

Investigators looked into one complaint and identified seven violations. The issues they described in their report included:

District did not consider parent input or recent student evaluations when creating an IEP.

School employees pressured the complainant to agree with a district decision regarding the student: “Based on this pressure from school personnel,” the complainant changed course to agree with the district. The complainant felt as if they were not being heard, and did not understand “how the outcome of the meeting would impact the future education of the student.”

District unilaterally made decisions about a student before an IEP meeting was held: The student’s parents felt the meeting was held quickly, school team members were already in complete agreement with each other, and their own thoughts and opinions “were fully disregarded.” The building administrator told each parent they needed to agree with the school team.

The district shifted its responsibilities to the parents: The district eliminated services and accommodations from a previous IEP, relied on the student’s family to provide support, and failed to provide services the student needed to participate in the general education classroom and progress toward goals.

Investigators looked into one complaint and identified six violations. The issues they described in their report included:

A student was kept from being educated with non-disabled peers:

- The district put the student in an educational setting usually reserved for students who had a weapon, used or possessed drugs, seriously harmed others while on school grounds, or was likely to harm others. Behavior logs did not show that any of these applied to the student.

- No IEP team meeting was held to determine the placement, and the complainant did not have the opportunity to participate in the decision.

- “The benefit of such a placement was solely to the district,” said the investigator, adding that the district failed in its duty to ensure the student was educated with non-disabled peers to the maximum extent possible.

Investigators looked into two complaints and identified six violations. The issues they described in their report included:

Inappropriate IEP: In one case, the student’s IEP was not designed to meet his or her needs.

A lack of progress monitoring data: There is no evidence indicating whether the 2022-23 or 2023-24 IEPs were fully implemented, or if the student made progress toward IEP goals.

Failure to provide services: A student’s IEP was not implemented at the beginning of the 2023-24 school year.

Impasse with a parent: In a second case, the district and complainant disagreed about where to place a student. “The district’s documentation indicates it took no action to resolve the parties’ disagreement and resulting impasse until after the complainant filed the complaint.”

Two districts where violations stood out: Teachers of students with disabilities manipulating grades; leaving aides to manage the classroom

A state investigation found five special education violations stemming from a December 2022 complaint. Here are the problems found:

An IEP meeting put off for five months: It took nearly five months and repeated requests from the complainant before the district held an IEP meeting to consider new information about the student in question. The investigator chastised the district for a delay that was “not reasonable.”

Goals for the student were “generic, vague and immeasurable:” This failure to include meaningful goals makes it impossible for the student’s IEP to meet their identified needs, which is a “substantive violation,” the investigator wrote.

Student grades were manipulated: According to the investigator, the student’s grades “were not only negotiable, but were manipulated. In fact, emails and interviews gave insight into the fact that students within the district are promoted with failing grades, and classes that the student had failed were changed to a passing grade.” Because of that, the student’s transcript and promotion to the next grade were not “reliable measures of ability or progress.”

Difficulty accessing student records: The district did not provide a signed copy of the IEP. “The complainant provided emails spanning the course of two calendar years … reflecting the complainant’s frustration regarding the inability to access the student’s educational records…”

Overall, the district did not provide appropriate services to the student: District practices do “not meet the threshold requirement of the Idaho Special Education Manual outlined above.”

Gary Tucker, Marsh Valley’s superintendent, said the complaint stems “from an issue that started in 2019 … Due to a lack of training and oversight, these errors had gone undetected for some time.”

Since the report was issued last year, Tucker said the district has improved its processes to better meet the needs of special education students, as the state required, including:

- Providing extensive additional training for administrators, teachers and aides.

- Providing makeup services that students may have missed out on.

- Moving the part-time special education director position to full-time.

“We recognize that we had some holes in our procedures and have worked diligently to bring our special education program into compliance,” Tucker said. “We support all of our students and will continue to do everything that we can to help them to be successful.”

A state investigator identified two violations after a complaint was made in June 2023. Here were the problems:

A classroom with an absent teacher and videos instead of instruction: The classroom teacher was often absent and repeatedly left early, leaving aides to manage the classroom, according to the report. The classroom also lacked structure — the students played all day; no individualized teaching occurred in the classroom; and the teacher showed videos instead of teaching.

Placing the student without involving the IEP team or parents: The district selected the student’s educational location without including the full IEP team or the student’s parents. Further, the investigator found the student’s placement to be inappropriate and determined by “zoning as opposed to student needs.” “At some point, school boundaries should have become a secondary issue to whether the student was receiving a (Free Appropriate Public Education),” the investigator wrote.

Karla LaOrange, Idaho Falls’ superintendent, said the district has since made improvements, including:

- Reaching out to the students’ parents to rebuild relationships.

- Providing staff training “to ensure that all teachers and staff have the appropriate skills and training to meet the educational needs of students with disabilities.”

“Idaho Falls School District is always looking for ways to improve student learning and meet the individual needs of all students,” LaOrange said. “The district will continue to be diligent in providing strong learning experiences for all students.”

Idaho Education News data analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.