Budget-setting lawmakers are raising “questions and concerns” about state funding for the Idaho Digital Learning Alliance (IDLA), the online learning platform, which could lead to policy changes in 2026.

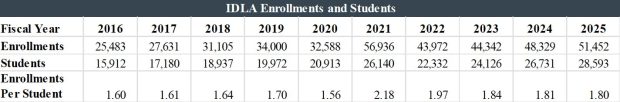

IDLA offers school districts and charter schools virtual courses to supplement their curriculum, often filling gaps in traditional school offerings, particularly in rural stretches of Idaho. Last fall, 28,953 students were enrolled in one or more IDLA courses. State funding covers most — but not all — of the costs to operate the platform and pay its teachers.

IDLA has flown under the Legislature’s radar since it was founded in 2002. But a surging state budget — up 158% since an enrollment spike during the COVID-19 pandemic — has prompted increasing scrutiny over its funding model and raised suggestions for alternatives, including online learning options in the private sector.

The Legislature’s Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee (JFAC) this year directed IDLA to deliver a report justifying expenses that support a nearly $26 million state budget. The report confirmed some of the concerns held by Idaho Falls Rep. Wendy Horman, JFAC’s Republican co-chair.

For one, it showed that IDLA students can be counted twice in state funding formulas — once for attendance at their brick-and-mortar school and once for taking an online course. Next legislative session, IDLA should be prepared for “direct conversations” about its funding, Horman said.

“This is an entity that has had very little sunshine on their budget,” she said. “So these are reasonable questions to ask on behalf of taxpayers.”

IDLA expands ‘opportunities’ with variety of courses

Amid the recent probe of the platform’s finances, IDLA superintendent Jeff Simmons has defended its funding model and emphasized that it’s a form of school choice, relied upon by rural communities.

IDLA has a variety of offerings, from dual credit — college-level courses that count toward an associate’s degree — to advanced placement, driver’s education and unique classes not typically offered by a traditional school district.

While IDLA is primarily geared toward students in middle school and high school, it also has resources for K-5. Its “Elementary Launchpad” connects classroom teachers with virtual instructors, who provide additional literacy coaching for students struggling to read.

Most IDLA students take more than one class at a time. Last fall, 28,953 students took an IDLA course, and total course enrollment was 51,452. That’s 1.8 course enrollments for every student.

Zoey Carothers, a 14-year-old from Grand View, is using IDLA to get a jump-start on science classes. She wants to be a nurse. Heading into her freshman year, Carothers has already taken a high school health class and courses in medical terminology and zoology.

“All my friends were sitting in the same classroom as me, doing junior high health. I was the only one doing high school health,” Carothers told EdNews. “(IDLA) gives me opportunities that I wouldn’t normally get through school.”

IDLA is accredited through Cognia, the same organization that provides accreditation for traditional public schools and charter schools serving grades nine through 12. Courses are reviewed by a third party, Quality Matters, and align with the National Standards for Quality Online Courses as well as the Idaho Department of Education’s content standards. The College Board approves IDLA’s advanced placement courses, and dual credit classes must meet the standards of the college or university awarding credit.

Last school year, 91% of IDLA students passed their courses. The average class size was 22 students. Certified teachers — most part-time, teaching one or two classes per semester — are paid based on the number of students enrolled in a class. Median pay per course was $3,600 last school year.

How is IDLA funded?

State funding doesn’t entirely cover IDLA’s costs. The platform also charges school districts fees for their students to enroll, and IDLA receives two rolling grants, one from Apple and another from Boise State University.

Here were IDLA’s main revenue sources during the 2024-25 school year:

- State funding — $21.4 million ($430 per enrollment)

- School district fees — $1.7 million (fees ranged from $15 to $75 per course)

- Grants – $224,000

Rural districts use IDLA at higher rate

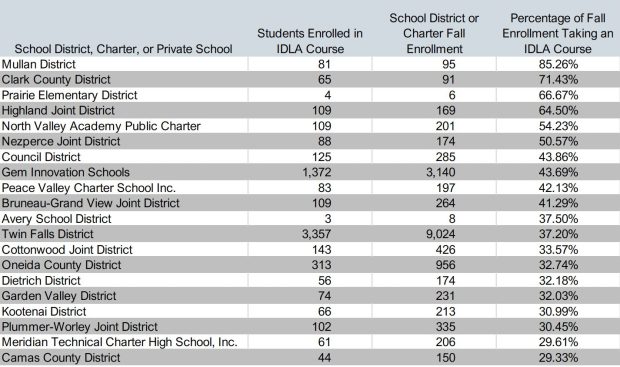

One in five rural public school students enroll in an IDLA course each school year compared to one in nine urban students, according to IDLA’s recent report to the Legislature.

Among the 38 traditional school districts with at least 20% of students using IDLA, the median district enrollment is 280, according to data published in a July report by the Legislative Services Office and analyzed by EdNews. Twenty-eight of these districts have fewer than 500 students. In Mullen, a small town east of Coeur d’Alene, 81 of its 95 public school district students are enrolled in IDLA.

That’s not to say urban schools don’t also use the platform. The Twin Falls School District has the highest number of students using IDLA at 3,357, or 32% of overall district enrollment. Gem Prep, a charter school network, is second, followed by West Ada, Nampa and Boise.

But for rural districts like Bruneau-Grand View — which has struggled to attract qualified teachers and has 41% of students enrolled in IDLA — the online platform helps level the playing field, said Katy Carothers.

Zoey’s mother has a 360-degree perspective on IDLA. Two of her four kids have taken online courses through the platform. She also serves as the Bruneau-Grand View School District’s IDLA paraprofessional, overseeing a classroom at Rimrock Junior/Senior High School where students complete virtual courses during the school day.

IDLA gives these students access to academic opportunities similar to those offered in wealthier and better-staffed urban districts, Katy Carothers said.

“I see both sides of it, and I realized how great of a program it truly is. I would hate to see it go away, because it’s my job, but also because I have kids that are invested and are doing amazing things.”

Controversial course fees typically passed on to students

Before 2023, lawmakers didn’t consider the IDLA’s budget as a standalone. It was a line item in the larger public schools budget.

Now, superintendent Simmons must report to the Legislature’s budget-setting committee alongside other state agency directors. While technically not a state agency — statute defines it as a “governmental entity” — IDLA is mostly funded by the state.

This fiscal year, IDLA will get $25.8 million from state coffers, a 158% increase since 2019, before enrollment spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic, and a 21% increase since last fiscal year.

In March, during the legislative session, JFAC members peppered Simmons with questions about IDLA — how it forecasts enrollment, how often students pass their courses and whether the platform could eliminate the fees it charges to districts and charters.

The fees cover IDLA’s costs where state funding falls short. In 2024-25, the state gave the platform $430 per course enrollment, but costs were $471 per enrollment, on average. IDLA charged school districts and charters between $15 and $75 per enrollment, which altogether raised $1.7 million for IDLA. That total could have been higher, but IDLA forgave $665,605 through scholarships and “zero-fee courses.”

This year, IDLA’s board of directors lowered top-line fees from $75 to $40, which will further decrease revenue from fees by about $1.1 million. The eight-member board includes three public school superintendents, two principals, two business community representatives and the state superintendent or a designee.

But that may not be enough to appease budget-setting lawmakers opposed to fees at any amount.

Horman has long been skeptical of the course fees, because most schools — about 62%, according to IDLA’s report — pass them along to students. As IDLA charges school districts and charter schools for access to courses, the schools charge students as they enroll. That’s a “problem” when it applies to graduation requirements, Horman said.

“My district tried to charge me,” Horman said. “I declined to pay, because it was a course my son needed to graduate, and I didn’t believe it was constitutional that they were charging me.”

JFAC ultimately lifted IDLA’s per-enrollment state appropriation, from $430 to $445, for the upcoming school year. This increase, meant to cover cost-of-living adjustments for teachers, came with some conditions, however: IDLA had to follow through on its plan to reduce course fees, and it had to deliver a detailed report on its expenses by Aug. 1.

Superintendent defends state funding model

The report showed that IDLA’s primary expense, unsurprisingly, is teachers.

Last school year, the platform spent $11.9 million on payroll for instructors and student supervisors. The second highest expense was technology — $4.7 million — followed by curriculum — $2.2 million.

Horman had one other takeaway from the report: It showed that the state is paying twice for each IDLA student. When a student enrolls in an online course, they count toward IDLA’s enrollment and toward their brick-and-mortar school’s average daily attendance (ADA), the formula that determines state funding for school districts and charters.

Taxpayers should fund IDLA and ADA but not both, Horman said. “We need to make some policy changes to make sure that taxpayers are not paying twice for the same student in the same course.”

But Simmons defended the current model. The ADA funding — none of which goes to IDLA — covers the responsibilities that schools retain with IDLA-enrolled students, he told EdNews. The brick-and-mortar school still has to keep academic records, administer exams, communicate with parents, provide technology access and offer campus services while monitoring students’ academics and discipline.

These students have “minimal to no impact” on a district or charter’s ADA calculation, Simmons said. The ADA formula fully funds a student when they have four hours of instruction, and most students already take four or more classes at their brick-and-mortar school.

“IDLA supplies curriculum, instruction, and the online platform; the enrolling school supplies day-to-day supervision and services,” said IDLA’s report to the Legislature. “This shared-responsibility model…ensures that both partners have resources to serve each student fully.”

Lawmakers mull possibilities in the private sector

These “questions and concerns” around IDLA’s funding could lead to policy changes next year, Horman said, but she doesn’t yet know specifics. More drastic steps have also been suggested.

Sen. Brian Lenney, a Republican from Nampa, last month asked the Legislature’s DOGE Task Force to recommend defunding IDLA and allowing private providers to take over the space.

Horman said she’s been a “fan” of IDLA since her son used the platform two decades ago. But she’s also intrigued by the potential for a private alternative.

One of the Statehouse’s leading advocates for private school choice, Horman co-sponsored a bill this year that created a tax credit for families who send their children to private school or a home-schooling setting like a learning pod. Parents increasingly want more control over their children’s education, Horman said, and while online learning was still an “innovative” model in the early 2000s, it’s more widespread now.

“I do think there is a place for the state to enable online learning opportunities for children. I’m thinking, very small charter schools. I’m thinking, rural school districts,” she said. “I’m also very interested in what the free market could provide.”

IDLA’s report highlighted ways it could “maintain efficient use of taxpayer dollars.” This includes revisiting course fee reductions, offering additional scholarships to students whose districts pass on fees and shifting 20% of its Launchpad sections to part-time teachers, saving about $600,000 on payroll.

If state funding holds steady next fiscal year, IDLA could absorb a course fee reduction from $40 per-enrollment to $35, the report said. IDLA is exempt, along with other K-12 institutions, from Gov. Brad Little’s executive order for 3% midyear spending cuts.

In the meantime, Simmons is spotlighting IDLA’s benefits. Eliminating it would remove “choice, accessibility, flexibility, quality and opportunities” for tens of thousands of students, he said.

“This impact would be severe on Idaho’s rural schools, which often don’t have additional choices to offer their students,” he said.