Since the 1980s, Caldwell students have studied politics and economics not in textbooks but through discussion. While not a novel concept — Socrates championed it thousands of years ago — this method made retiring teacher Steve Hauge beloved, and feared, at Caldwell High School for 40 years.

Colleagues and former students are celebrating Hauge this month as he prepares for retirement after four decades in public education. Hauge’s career stands apart not just for the “extremely uncommon” length of his tenure, said former Caldwell High School principal Julie Yamamoto, but also for his ability to engage students and show them how to think for themselves.

“What a gift he has been to public education over that 40-year span,” Yamamoto told Idaho Education News. “The number of people’s lives that he has changed, whether it be a student, other staff members or parents, is just incalculable.”

Hauge started teaching economics — a graduation requirement for Caldwell high schoolers — in 1985. A few years later, he took over the political philosophy course, an advanced government class designed for seniors, whose reading list more closely resembled a college-level philosophy seminar than high school social studies.

Hauge asked his students to read Plato’s “Republic” along with the works of Aristotle and Alexis de Tocqueville. In the classroom, they engaged in a Socratic seminar with group discussions followed by probing questions from Hauge. And in the final paper, students were asked to explain how a meaningful idea discussed during the semester changed their worldview.

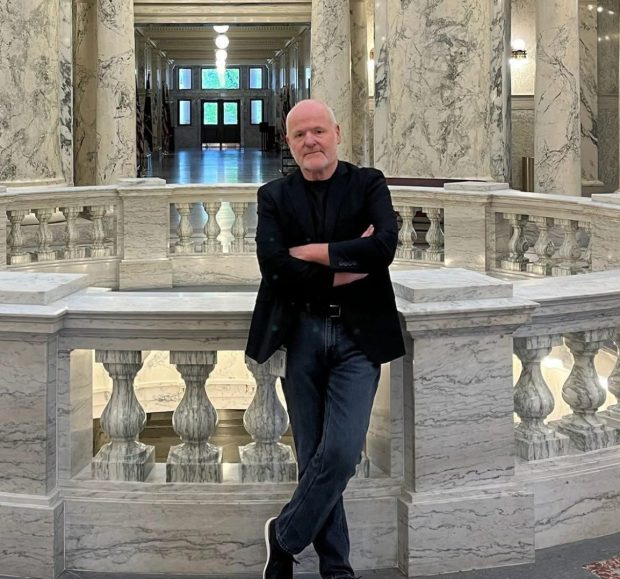

“If you’re just memorizing, regurgitating, you’re Teflon,” Hauge told EdNews in a recent interview at his Nampa home. “Education is supposed to transform you. When I read different people, different things, I change my opinion. That’s what education is.”

Teaching through discussion

A Minnesota native, Hauge moved to Idaho in the 1970s and turned to teaching in his late 20s after a stint as a technical writer. He also wrote sports columns on the side.

Hauge developed his teaching method early in his career, after visiting a friend at a liberal arts college. Students there studied the Great Books and engaged in animated roundtable seminars. Hauge participated in one discussion that focused on a single paragraph from Aristotle and lasted well into the night. “I’d never been that excited talking about anything,” Hauge said.

From then on, Hauge used similar roundtables in his classes. Students “incubated” in small group discussions facilitated by a student leader. While they “learn far more from each other than they will from me,” Hauge said, students still had to be prepared for his questions.

“I really don’t believe anyone learns unless they’re talking with other people,” he said. “We don’t know what we don’t know until somebody asks a question.”

Yamamoto, Hauge’s former supervisor, said she often observed his classes, “to see what quality teaching looked like.” And she advised other teachers to sit in and take notes.

Hauge had the best “wait-time” that Yamamoto had seen, she said. Wait-time is a teacher’s pause after asking a question and before soliciting an answer — the longer the pause, the more time a student has to gather their thoughts. Hauge asked pertinent questions that led to other questions and gave students the time, and just enough information, to form their own opinions, she said.

“The man was masterful,” Yamamoto said. “He got it.”

Yamamoto later served in the Idaho House, after more than 30 years as a public school educator, and she would meet with Hauge’s political philosophy students on field trips to the Statehouse. The students met with the governor, secretary of state, lawmakers and judges, and they always came with thoughtful questions, Yamamoto said.

“He created in them a hunger to know,” she said.

Meeting students on their terms

Hauge’s reputation as a tough teacher made students afraid to take his class, said Brennan Wurtz, chair of Caldwell High School’s social studies department, who has taught alongside Hauge for a decade.

But after taking his classes, students loved Hauge, Wurtz said.

“He challenges them to figure things out themselves, because he knows that they can,” Wurtz said. “Every kid in school knows who he is, because he is beloved and he’s very funny. … He’s very sociable and can talk to kids easily.”

Sociability isn’t just a character trait, it’s also a teaching strategy. Hauge translated highbrow concepts into relatable terms for teenagers, like comparing economics to their jobs or school work and tying politics to high school social life.

The beauty of economics, for instance, is incentives, Hauge said. At the start of each economics semester, he posed this question: What kind of effort would you put into the class if everyone was guaranteed an A grade? None, because there would be no incentive.

And the key to political philosophy is the individual’s appetite for power, the same aspect of human nature that shapes high school cliques and permeates lunch-table gossip.

“They want to talk about themselves,” Hauge said. “If you teach in a conversational manner, you will go so far. If you’re talking at them, it won’t go anywhere.”

Still, Hauge had high expectations for his students, Wurtz said, and his political philosophy class tended to attract students who were on track to attend good colleges. That’s partly because he taught it like a college seminar, with heavy reading assignments and the expectation that students would be prepared for discussion.

“It’ll be hard to replace him, just his personality and his presence,” Wurtz said.

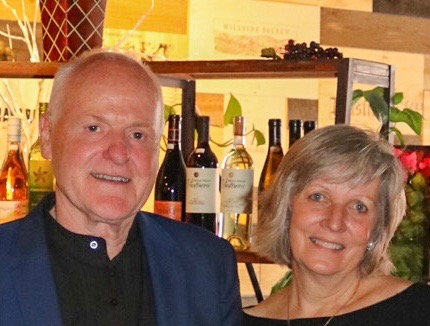

In retirement, Hauge said he’s looking forward to spending time with his seven grandchildren.

But he worries about the future of his calling. Across public education, students’ home lives have become less stable compared to 40 years ago, he said. And teachers are tasked with addressing a growing number of students’ challenges, from learning disabilities to language deficiencies and behavior problems, all in a single classroom.

Hauge said he’s a “boiled frog” who’s learned how to make it work. But expecting that teachers can accommodate each student’s individual needs in one room, without lowering the bar for learning, is “wishful thinking.”

“New teachers come in, and they’re intimidated by all of the hoops they have to jump through in order to just have instruction,” he said.

Inspiring ‘thousands of students’

Almost every Caldwell High School graduate since the class of 1986 took Hauge’s economics class, according to Wurtz. Several prominent members of the Caldwell community, including the mayor, and “countless educators” are former students, Wurtz said.

Hauge is one of the “all-time greats,” said Mayor Jarom Wagoner, a 1995 Caldwell High School graduate. Wagoner said he’s among the thousands of students that Hauge “touched for good.”

“It is difficult to put into words the impact he has had on the Caldwell community, and truly across the globe as he has inspired thousands of students that have gone on to achieve incredible success,” Wagoner told EdNews by email. “Mr. Hauge has always been engaging and endearing to all of his students, with his quick wit and sense of humor.”

When asked about his impact on students, Hauge declined to answer at first, not wanting to boast. But after some “wait-time,” he admitted to feeling guilty. Amid the overwhelming praise for his teaching career, Hauge recalled what he’s gotten out of it — so much fun in the classroom, doing what he loves.

“I feel like the students have done far more for me than I’ve ever done for them,” he said.