The new year is shaping up to be another hectic one for education policy as the Idaho Legislature prepares for its next session.

Questions abound:

- Will public schools remain exempt from budget cuts?

- Where can Idaho train new doctors to ease a physician shortage?

- Will private school choice pass constitutional muster?

- Are online students really getting taxpayer money for water park tickets and meat thermometers?

Not ready to confront another year of politics? Click here for our 2025 year in review and reminisce about the old days.

These are some of the issues EdNews will be following in 2026.

Oh, and don’t forget, it’s also an election year.

Here are five things we’ll be covering:

Budget deficit

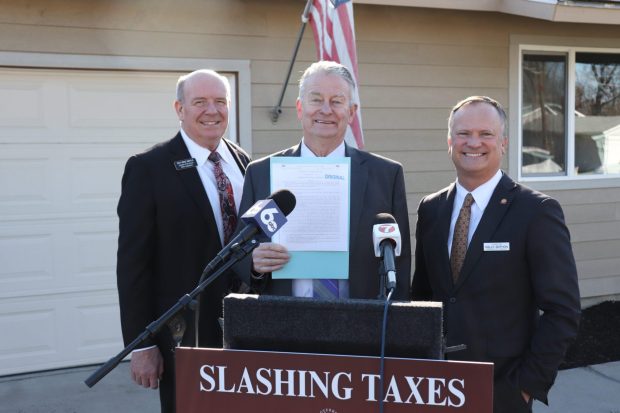

When lawmakers return to the Statehouse next week their first order of business should be resolving a budget deficit that followed last year’s historic tax cuts.

During the 2025 legislative session, budget-setting lawmakers set a high revenue target that made room for a suite of GOP-backed tax cuts and credits, altogether worth about $453 million, just as the state’s sales tax revenue started to slow down.

The result was an estimated $40 million deficit for the current fiscal year, and a much larger red number on next fiscal year’s expense sheet. State agency budget requests for fiscal year 2027 — which starts July 1 — exceed projected revenue by about $555 million.

These figures don’t include the impact of conforming to tax changes in President Donald Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill Act.” The Republican-dominated Legislature will have a choice: Conform to the federal tax changes, which could cost the state $284 million; or don’t conform and explain that decision to voters who overwhelmingly supported Trump.

Over the summer, Gov. Brad Little directed state agencies to cut 3% from their budgets, which helped ease the deficit. It cost colleges and universities a combined $13.3 million, leading to staff reductions. K-12 public schools have been exempt from the cuts — so far.

Lawmakers will need to find up to $1 billion if they want to resolve this year’s deficit and balance next year’s budget while leaving a cushion on the bottom line, the Idaho Capital Sun reported.

Expect some serious debate over how to get there.

Special education

Last year, the Legislature made no progress addressing an $82.2 million gap in special education funding for K-12 public schools. Now, the problem has grown to $100 million, and the aforementioned budget deficit has already stalled one plan to chip away at it.

State superintendent Debbie Critchfield last month hit pause on her $50 million special education block grant proposal. The Republican has other — cheaper — ideas: launching regional special education support centers and creating a high-needs student account by shifting money from other programs.

Sound familiar? Lawmakers narrowly rejected a proposal to create a $3 million high-needs fund last session. The defeating vote came a couple weeks after the nonpartisan Office of Performance Evaluations released a report that showed the state’s special education funding model is falling short of supporting all students.

Increasing this support is the top priority for public school trustees heading into legislative session. The Idaho School Boards Association (ISBA) last month adopted a resolution that pointed to rising costs of “personnel, specialized transportation, assistive technology, individualized instructional materials, and required staffing ratios.”

Want to hear more about the upcoming legislative session from two veteran Statehouse lobbyists? Click here for a session preview podcast.

When state and federal funds fall short, school districts lean on local taxpayers to support special education students, who have a legal right to the services they require. Quinn Perry, deputy director for the Idaho School Boards Association, told EdNews this week that it’s not just a legal responsibility but a moral one, too.

“This state needs to have a serious and meaningful conversation about what it’s doing … when it comes to funding special education,” Perry said.

Private school choice

No, we’re not done talking about private school choice, despite last year’s passage of House Bill 93. In fact, we’ve got a long way to go.

On Jan. 23, the Idaho Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in a constitutional challenge to HB 93’s Parental Choice Tax Credit, a refundable tax credit covering private-school tuition and home-school expenses. The case has garnered national interest, and it could be decided during this year’s legislative session.

Meanwhile, applications for the tax credits are set to open as scheduled next week. They’ll be issued on a first-come, first-served basis, with priority given to households that earn 300% or below the federal poverty level. The Idaho State Tax Commission — the agency responsible for administering the credits — will collect data on the recipients, and compile a waitlist if applicants exceed the available funding.

Need help following education issues during the legislative session? Click here for EdNews’ guide with key dates, committees to watch and ways to participate.

A big waitlist could embolden supporters to lift the $50 million cap — perhaps not this legislative session, during a tight budget year, but eventually. That is, if the Supreme Court upholds the program.

Idaho’s new tax credit isn’t the only school choice program in limbo. The “Big Beautiful Bill Act” included a new federal education tax credit that states can opt into. It’s a $1,700 credit for contributions to nonprofit “scholarship granting organizations” (SGOs) that help public- and private-school students cover education expenses.

If Idaho lawmakers want to participate, it could take legislative action to create SGOs, then another bill to opt into the federal program.

Medical education

Idaho now has a plan to bolster medical education and help ease a statewide doctor shortage. Whether the plan turns to action is another story, which should unfold in the coming months.

Last year, college and university leaders across the region pitched a state task force with ideas that would altogether create hundreds of state-subsidized medical school seats in Idaho. This included a proposal for Idaho State University to buy the Idaho College of Osteopathic Medicine, a private medical school in Meridian.

After considering the proposals this fall, the task force delivered its own recommendations to the governor and lawmakers last week.

The task force’s plan calls for sustaining Idaho’s current medical school partnerships, with the University of Washington and University of Utah, while subsidizing additional seats at the Salt Lake City-based medical school. It also recommends buying, for the first time, seats at ICOM. But it doesn’t endorse — or reject — ISU’s potential bid to purchase the school.

Idaho currently pays $7.6 million per year for 40 medical school seats at WWAMI, the University of Washington’s regional medical program. Idaho spends nearly $3.1 million for 10 seats at Utah.

Additional seats will come with an added cost, of course. It’s now up to the Legislature whether to fund the task force’s recommendations or come up with its own path forward.

In the meantime, Idaho ranks 50th nationally for physicians per capita. And did we mention that money will be tight this session?

Virtual schools

Idaho’s public virtual schools could be under a microscope this year after a recent report highlighted questionable practices at a massive online school.

The Office of Performance Evaluation’s report last month found that the Idaho Home Learning Academy — a virtual charter school with 7,600 students — took state funding earmarked for teacher pay and gave it to private education vendors. The vendors then dished out $12.6 million to IHLA parents in reimbursements for “supplemental learning” materials.

The funding shift is legal — or at least not prohibited by law. But some of the reimbursed expenses stretched the meaning of learning material. The inventory of taxpayer-funded purchases included water park tickets, MP3 players and even a meat thermometer.

Meanwhile, IHLA’s test scores lag 12 and 18 percentage points behind statewide averages in English language arts and math proficiency, respectively.

The OPE report recommended lawmakers increase oversight of virtual schools.

But it’s not as simple as it might sound.

IHLA’s fan base is large and motivated, and legislators that advocate for “education freedom” could stand opposed to regulating an education option that’s popular with parents that used to home-school their children.

EdNews Senior Reporter Kevin Richert contributed to this report.