GRANGEVILLE — A long-simmering division between Idaho County’s two largest communities will reach a crossroads this spring.

Reeling from four consecutive levy defeats, Mountain View School District will appeal to the taxpayers of Kooskia and Grangeville one last time May 21 before closing Clearwater Valley High School and Elk City School.

“If we don’t pass the levy, that’s what’s going to happen,” said trustee Tyler Harrington, the school board’s chairperson.

What’s more, voter displeasure laid bare years of disenchantment and resentment. Last spring, a survey revealed that 82% of parents and students favor deconsolidation, or splitting into two separate districts.

“Community interest is driving this deconsolidation,” said Kim Spacek, the district’s superintendent.

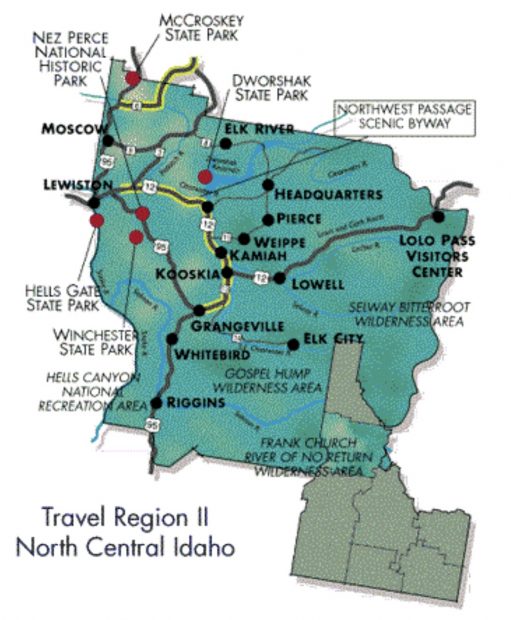

The six miles of steep, twisting blacktop called Harpster Grade is roughly where the communities diverge. Grangeville sits above the grade and the towns of Kooskia, Clearwater, Stites and Harpster — Clearwater Valley — are along the South Fork of the Clearwater River.

For deconsolidation to pass, both communities must approve. A specific election day has not been selected. Maybe later this year, in November, or early next year.

But the referendum will definitely be on the ballot, Harrington confirmed.

“You can’t force this on any community. If you don’t want to split, then don’t do it,” he said.

A lot hinges on the levy’s outcome. If it passes, Harrington wants a unified district working cohesively to improve all schools. And if it fails, Kooskia will need to part ways with Mountain View to keep Clearwater Valley High School open. Closing it would affect a way of life.

School trustee Bernadette Edwards believes Kooskia will succeed financially because self-governance and fiscal autonomy will rally support for their schools.

“Closing Clearwater high school is not what we want,” Edwards said. “If there is a different option, we would be using it.”

Recent development: trustees find common ground on levy ask

At a special meeting last Monday, the board agreed unanimously to request a $2.9 million per year levy, for a total of $5.8 million over two years. The unified vote was a welcome change.

“It eased the emotions in the community and the tension in the room,” said Sara Daugherty, who lives in Harpster and has two children attending Mountain View schools.

The narrative is changing with new faces on the board (Harrington and Jon Menough) and a concerted effort for transparency and better communication — accepting more input and opportunities for interaction.

Levy money would help the district get by but not solve long-term funding needs. There are very little reserves and a long list of deferred maintenance problems.

During peak years, the district received upwards of $3 million per year from federal timber dollars but that is down 66%, and inconsistent.

“We don’t want to close the school but there is no choice,” Harrington said. “It’s pure economics.”

The cost to educate Clearwater high school and Elk City students is the highest in the district. It spends $14,812 per student at Clearwater and $21,787 at Elk City. Grangville is $10,475 per student. In Grangeville, there are 838 students; Elk City and Clearwater combined have 331.

The previous one-year levy failure asks are as follows: $3.1 million per year in 2023; $1.7 million in 2022; $3.1 million in 2021; and $3.9 million in 2020.

Similar cultures but they don’t agree on school funding

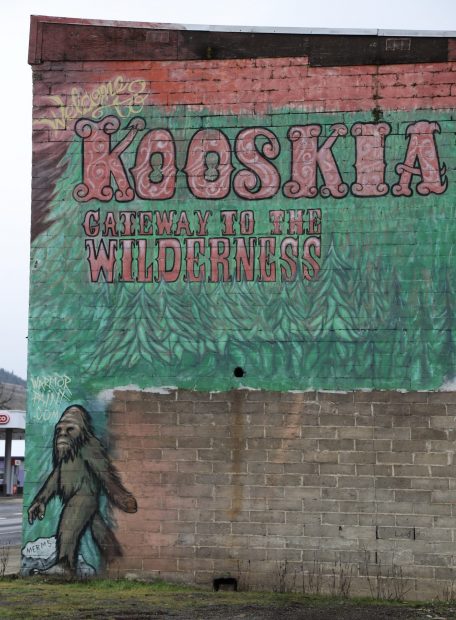

On the drive down to Kooskia, morning fog drooped over the river and timbered slopes. Muddy pickup trucks darted off to jobs at the mill or welding shops. An elderly lady sipped coffee on her porch and a fisherman unhooked tall rods mounted to his truck.

Many voters in the valley say there’s a funding imbalance, so the towns of Clearwater, Harpster, Kooskia, Kamiah and Stites consistently vote against school levies.

“I wish that perception didn’t exist,” Daugherty said.

But it does.

Harrington said, “They see things differently.”

At the Kooskia Cafe, morning patrons drifted in and out while waitress Lacey Ash, who has three kids in local schools, kept coffee mugs topped off. The cafe’s walls are full of local history, dating back to the late 1800s.

Local chatter centers on two thoughts — all citizens should fund schools, not just property owners, and most of the money is going to Grangeville.

“And we get the hand-me-downs,” Ash said, who voted in favor of the levy because she wants her schools to remain open.

That perception was echoed by business owners, grandmothers, librarians and school administrators.

“I don’t want them driving up to Grangeville in the wintertime. Those roads are terrible,” Ash said. ‘I graduated from Clearwater high school, and I want my kids to do the same.”

Mark Hargens was just finishing breakfast. He voted against the levy.

“We can’t really afford the taxes the way it is,” Hargens said. “How are they spending $3 million in one year? That was a ‘no’ for me.”

If you’re in the valley, stop by the cafe for a strong cup of coffee and a signature Kooskia Muddle — hashbrowns layered with sauteed pepper and onion, diced ham and cheddar cheese, and topped with tomatoes.

An online reviewer wrote, “If I find myself in Kooskia again, I would definitely eat here.”

One of the state’s largest geographic districts

Mountain View occupies a vast geographic footprint. The National Forest Service manages 4.2 million acres and the Bureau of Land Management handles just under 60,000.

The area encompasses five national forests: Nez Perce-Clearwater, Bitterroot, Payette, Salmon-Challis and the Wallowa-Whitman. Montana sits on its eastern boundary and Oregon to the west.

Locals say they don’t live here for the weather or the great streets and sidewalks. They live here for the way of life.