West Ada’s Future Farmers of America teachers are rolling up their Carhartt sleeves for a 21st Century mission: help young people become agriculture cheerleaders.

Their efforts are paying off.

Urban students with little to no experience are gaining an appreciation and understanding of what it means to be an Idaho farmer or rancher.

In the Treasure Valley, where subdivisions and stripmalls are encroaching and replacing farmland and pastures, an increasing number of students are discovering what the agriculture industry has to offer.

During a recent class at Meridian High School, senior Keeley Joslin said she’s thinking about switching from business to a veterinary science degree.

The veterinary science class “showed me if I want to go into the field or not. And I definitely do want to be in the field,” Joslin said.

The number of high school students enrolled in agriculture-related classes statewide in the past five years has increased 38%, from 13,470 to 18,648, according to the Idaho Division of Career Technical Education.

Although students in the big school districts like Nampa and Kuna and West Ada have fewer opportunities to bail hay, feed livestock and haul water, having little farm experience is not necessarily a negative for educators.

“We are able to get a more diverse group of students because of urbanization, so I don’t view it as a bad thing,” said Larie Trotter, a Meridian FFA advisor and ag teacher.

Change is inevitable, but they are embracing it.

Any student with an interest or passion in agriculture — including plants, trade careers or leadership activities — are that new generation helping statewide enrollment grow by a little more than 7% each year, according to the Idaho Division of Career Technical Education.

However, living on a farm or showing livestock animals at the county fair are not prerequisites.

“It’s refreshing being around kids who are okay with not knowing about agriculture and still being excited to work,” said Elizabeth Russell, an FFA teacher at Centennial High School.

Idaho students are still interested in agriculture

The Treasure Valley’s unprecedented population and housing growth is affecting agriculture education in an unexpected way: student participation is increasing.

At West Ada — Idaho’s largest school district — participation in agriculture classes increased by 11% in the past year. In 2021, approximately 2,278 students were enrolled in ag classes; last year around 2,536 signed up. About 25% of all West Ada high school students are enrolled in agriculture-related classes.

“A lot of our farmland has disappeared and been replaced with subdivisions, shopping centers, and new infrastructure to support the growing population. We have noticed that quite a few of our FFA members are now a couple generations removed from agriculture,” said Staci Low, West Ada’s director of career technical education.

And with that urban sprawl and fewer farms, one would expect the opposite: young people would grow less interested in agriculture-related programs — not true.

“I’ve noticed with freshmen in the introduction to animal science class, it’s like they’re hanging on to every single one of our words. They’re so interested in the information, that it just blows them away,” Trotter said.

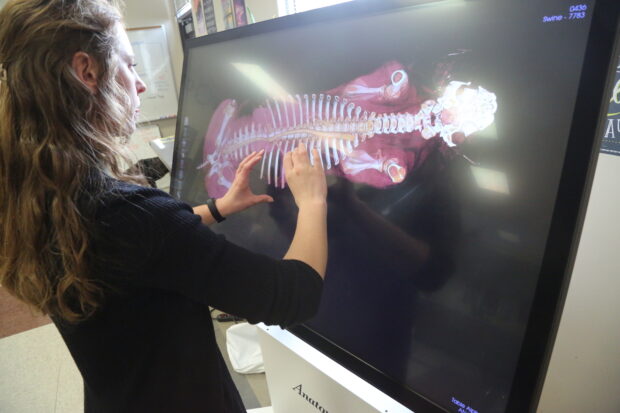

Jessica Higer, a Meridian FFA advisor and animal science teacher, brought in baby pigs for a basic anatomy lesson — and a dose of reality.

“My students were terrified,” Higer said.

“They had to touch the body and the nose. And they would touch the body and say, ‘Oh my gosh. It’s rough. It’s hard.’ Then they touch the nose. And more kids were shocked: ‘It’s a soft, supple, cute little nose.’

“It makes it practical for them to see themselves in that industry,” Higer said.

Teachers on the frontlines of agriculture education

Because of growing environmental concerns and a generation gap, Idaho teachers in urban schools are struggling on two fronts.

They are attempting to correct misconceptions and educating young people who are three or four generations away from the farm, and may not understand where their food comes from.

Trotter grew up in Wilder working on a small cow-calf operation and attended Notus High School where she participated in ag programs. She attended the University of Idaho and expected to teach at a small school like Notus, but ended up at one of the largest.

“What I’m most proud about is actually getting to teach at an urban school and share the passion of agriculture with my students. I get to share with them how I grew up, how I’m still living now, and share with them the cool things that I get to do,” Trotter said.

Educators hunger for that “aha moment” when students truly connect with a concept or gain meaningful insight. For Trotter, that happens when students want to become a plant geneticist or study animal nutrition.

“It makes me feel good,” she said.

There are 14 agricultural teachers in West Ada. They teach welding, plant science, animal science or small gas engines, called pathways, at five feeder high schools — Centennial, Eagle, Rocky Mountain, Mountain View and Owyhee — and one main CTE center at Meridian. Feeder schools provide introductory courses. Later, students travel to Meridian for the intermediate and capstone courses to complete their pathways.

On the second floor of Centennial — one of five feeder schools — down a long hallway, Russell arranged some books in her classroom, home to a miniature greenhouse of sorts, and a variety of healthy-looking plants. There’s a life-size cutout of John Wayne over in the corner.

It pretty much resembles most classrooms. The reality for today’s FFA advisors is that it’s not just about cows and corn; they’re developing future biologists, chemists, veterinarians, engineers and entrepreneurs.

But farming and ranching remains the foundation.

“It can be frustrating from the producer standpoint,” Russell said. “You’re a minority population. You have one-point -something percent that are actually farmers and ranchers in this country. And somehow they’re able to feed everybody, plus many other parts of the world.”

Many Americans, Russell said, have very little understanding of the importance of farming, yet they express negative comments about it.

“But the teacher in me sees that as an opportunity. You can really get a kid to have a whole different mindset. That’s the nice thing about working with young people, they’re kind of an open book. They’re here to experience things and learn things,” Russell said.

Maintaining a connection to the land

Because of the area’s urbanization, there are fewer opportunities for FFA students to raise large animals — steer, sheep, pigs — for a fair project. Kids don’t live on a couple of acres.

The solution is a collaboration with farmers and ranchers who have available land.

“Our community members have really stepped up and allowed us to have some of our students house their animals at their property,” Trotter said. “So they have been able to have that same experience that I did where I raised steers through my high school career.”

Social media is a main source of negative agriculture news, she added. “They’re being fed that agriculture is bad for everybody, like we’re ruining the environment.”

Once exposed to the programs, students learn the truth about agriculture, and that shifts their perspective.

“They’re kind of like sponges and they just soak it up and they love it,” said Trotter. “So they (develop) a passion for animals, plants, welding, or speaking contests.”

Across Idaho, there are 100 FFA chapters with 6,150 students participating. The oldest chapter is Malad High School, and the largest is Minico High School, with 492 members, according to the Idaho Division of Career Technical Education. The Meridian chapter has 183 members.