I called it “Teacher Christmas” – those weeks before graduation when students would stop in the hallway or come up to my desk and hand me white envelopes with my name scrawled on them.

Inside would be graduation announcements, often detailing their future plans and dreams.

To me, they were the greatest gifts.

I would carefully tape each announcement to my cupboard doors, eventually wallpapering them with bright, smiling photos of former students. Seeing those announcements each day filled me with hope and reminded me why I taught.

The first time I considered quitting teaching, it was that wall of beaming mugs that convinced me to stay.

Those students are worth all the heartache that goes along with being an American public school teacher, I thought, and no other career could possibly be as rewarding as helping them launch into the rest of their lives.

But months later, my resolve winnowed again and I started searching for a new job – one outside of the classroom.

I agonized over the decision to leave education, because I did love teaching, my students, and my content area. But the pandemic, the politicization of education, fears of a school shooting, low pay, and public disrespect were beginning to outweigh those positives. As the saying goes – I loved teaching, but not being a teacher.

Ultimately, I decided to leave the profession.

After telling my principal the news, I felt guilty, like I had let everyone down – my administrators, my fellow teachers, and most importantly – my students. But in the weeks to follow, my whole being felt lighter – an airiness and freedom that made me feel positively buoyant.

I had forgotten what joyous felt like.

When I shared the news with my department, one of my colleagues jokingly suggested that my first article for my new gig as a reporter at Idaho Education News should be titled: “How to lose a teacher in eight years.” This isn’t quite that – but it is the story of how this Idaho teacher went from an idealistic, hopeful new educator to one who was ready to close the classroom door for good.

Friends, family and mentors warned me – don’t become a teacher. I did anyway.

Ever since I can remember, I wanted to be a teacher – and pretended to be one every chance I got.

As a kid, I watched my mom, a middle school science teacher, grade papers with a red pen. I remember pilfering one of those papers and a red pen and drawing my own childlike feedback all over it – smiley faces, Wow! – that kind of thing. My mom wasn’t happy when she saw her student’s heavily-decorated lab report.

In grade school when we got to wear costumes to school for Halloween, I came dressed as a teacher – with glasses, a button-up shirt, a pen tucked behind my ear, and an apple in hand.

And in high school I remembered asking my senior English teacher when she was going to retire, hoping I could take her spot the moment I finished college.

But by the time I declared a college major, I chose journalism.

My mom sighed with relief when I told her I wouldn’t become a teacher after all. She’d been advising me against entering her career for years.

“Don’t do it,” she’d always say, shaking her head.

It wasn’t the kids that made teaching hard, she said; it was all the other stuff – parents, politics, society.

I followed her advice for a while, becoming a newspaper journalist followed by a brief foray as a wildland firefighter. But teaching was always in the back of my mind – a siren call that I couldn’t ignore.

Fighting the five-year average statistic

One of my high school English teachers inspired me to become a teacher. Her passion for literature and writing was contagious. She could take an archaic, difficult text like Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter and make it a student favorite.

In her class, our discussions about literature were segues into philosophical discussions about human nature, society, and morality. I loved it, and I wanted to help create that same magic for students.

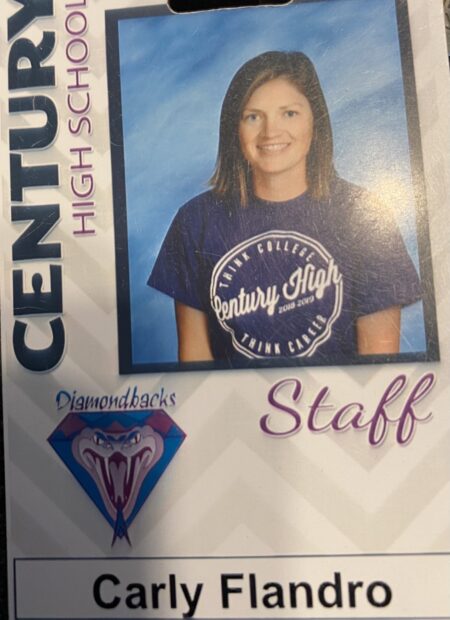

So, after reporting and fighting fire, I decided to go for it once and for all. I got my teacher’s certificate and started teaching at Pocatello’s Century High School in 2014.

My first year, I ran into that inspirational teacher at a training. She was preparing to become a principal. I asked her why she didn’t want to continue teaching, and she said something to this effect: “I probably shouldn’t tell you this in your first year, but the grading is crushing. You won’t be able to keep it up forever.”

I felt deflated by her matter-of-fact conclusion.

But she wasn’t the only person who made me question whether I could last as a teacher. One family friend said if I was determined to teach I’d better do it in Wyoming, where teachers make significantly more money. Idaho wouldn’t be worth my time.

I also watched two older cousins get education degrees and teach for a few years before drifting out of the profession. They both took breaks and said they’d go back to it, but never did.

And a friend of mine who was a former BLM hotshot firefighter – a position infamous for its grueling work – became a middle school teacher and said it was far more difficult than hotshotting had ever been.

On top of all this, there was a statistic that I kept hearing: most teachers only last for an average of five years.

These comments, observations, and stats should’ve served as red flags, but instead fired up my resolve to prove them all wrong.

I did make it past that five-year mark – but only by three years.

What made me close the door on my classroom forever

Last fall, I found myself shopping online for a bulletproof vest that would fit under my teacher cardigans.

At some point, I realized how troubling it was that I was looking for protective gear normally reserved for police officers.

But I felt like it was the only way to protect myself from the threat of school shootings that hangs over teachers’ heads like a dark cloud.

When the fire alarm went off in my school, we stayed in class until an administrator excused us over the intercom – verification that a shooter did not pull it to flood the hallways with potential targets.

When I heard loud banging noises from the floor above me, I wondered if it was from gunshots or running footsteps. I would pause, waiting to see if the noises were followed by screams. If not, I’d continue teaching.

When I heard screaming, fighting, or swearing coming from the hallway, I’d hope they were coming from unarmed individuals.

When my classroom door would open, I would hold my breath, hoping it wasn’t someone with a gun.

And it never was – thank goodness.

As a teacher, it was my job to protect my students at all costs. If the day ever came when a shooter entered my class, I hoped I would be brave enough to fight back and take a bullet for students if needed.

But in all the above scenarios, all I could really do was hope. And hope no longer felt like enough protection from gun violence.

I also questioned myself – am I ridiculous for worrying about a shooting? Chances are that it won’t happen. There’s probably a greater chance of being struck by lightning. Driving is far more dangerous and I do that every day.

But the self-inflicted gaslighting didn’t last long, because then I’d think about televised interviews with teachers and students from schools where shootings did happen. And they all said the same thing – “We never thought it would happen to us, and it did. It can happen to you, too.”

And I tried to take that message to heart. In my mind, I had a fully-developed action plan for what to do in the event of a shooter. I went over it repeatedly so if it did happen, I would not hesitate and my reaction would be muscle memory.

But what if I were gone and a sub were in my class when it happened? Would they know what to do? Or what if all my planning did no good – if I weren’t near enough to the door to lock it in time, or if a shooting occurred at lunch when kids were in the halls and common area?

There were so many ifs, so much breath-holding, so much hoping. And eventually, it wore me out.

But it wasn’t just a fear for my own safety and that of my students that drove me away from teaching.

My internal struggle

When I was debating stepping away from teaching, I decided to write out my reasons for leaving the profession.

I ended up scribbling out a list that was pages long – too long (and in some cases too personal) to replicate here.

But here are some of the reasons I felt burned out:

- The pandemic (adjusting to remote/hybrid teaching, feeling the brunt of the pendulum swing from public adoration to ire toward teachers, working extra hard to alleviate students’ learning loss/mental health issues – the list goes on)

- Lack of a work-life balance; an intense, unsustainable workload (lesson planning, grading, communication with parents, extracurricular responsibilities and meetings, etc.)

- A perceived lack of respect and trust from the public toward teachers in general

- Low pay considering the level of education, hours worked, and stressors involved in teaching

And here are some of the reasons that made it hard to leave:

- The people (Students and fellow teachers)

- The content area (I truly love reading, literature, rhetoric, and writing)

- The rewarding moments (Like hearing the news that my student got into their college of choice; watching them march across the stage on graduation day; listening to a thoughtful and tolerant student discussion; reading an extraordinary essay after a student struggled to get it just right)

- The close link to my identity (Who was I if not a teacher?)

I also felt torn because I’d invested so much time and money into this career – earning my teaching certificate and a Master’s degree, building up years’ worth of lesson plans, gaining expertise through hard work – how could I possibly walk away?

But the thought of 25 more years in education was daunting. And I remembered my mom’s own retirement reception (which honored all of that year’s retirees), when the superintendent at the time read Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree. (The classic children’s book is a depressing tale of a tree who lets herself be cut down to a stump in order to support a boy as he grows up).

“I am not a stump!” my mom indignantly said afterward.

I laughed then, but after eight years as a teacher, that metaphor was starting to resonate far too much – so many educators give so much of themselves that there’s not much left. And as my mom expressed that day, that’s not something to celebrate.

So I decided to leave while there was still some tree left in me.

My last day

In the last few minutes of the last class I would ever teach, I invited my students to pluck my art – dozens of tiny, framed literary quotes – off the walls and take them home as keepsakes.

Within minutes, the walls were bare. We said our goodbyes, the bell rang, and the students disappeared out the door. And just like that, I was no longer a teacher.

I remember packing up my things on my last day. My classroom was transformed. Once filled with colorful bulletin boards and literary posters and bright decorations (fully funded by me of course), it was now barren, reduced to plain white walls, old stained carpet, and an ant infestation along one wall.

Stripped of all my efforts, the classroom was just a vacant, heartless place – institutional and cold. It was another reminder of how little teachers are given to work with and how much they pour back in return.

I felt bad for the next teacher who, like me, would empty her pockets and her heart to fill this place with the resources and love that a classroom full of kids needs. And I hoped the giving wouldn’t turn her into a stump, that she’d establish boundaries and prioritize her needs, even if doing so felt like being selfish. Because ultimately, that’s what long-term giving (teaching) requires.

At the same time, the onus to make teaching a sustainable career isn’t just on educators. Society shoulders the responsibility, too. What can parents, students, communities, and politicians do? For a start, listen to what teachers and educational experts have to say – and this series is an opportunity to do just that.