Idaho teachers tell us their profession is becoming untenable in the face of disrespect, low pay, increasing workloads, aging facilities and increasing expectations.

Even so, most want to stay, though they tell us they are losing their grip. Many wish that parents, politicians, and community members would listen to their pleas and ideas before making decisions or forming hasty conclusions about Idaho's education system.

Here’s a chance to do just that. In their own words, here’s what Idaho’s teachers are saying about the state of education.

Colby Donicht

Borah High

Boise School District

English teacher

Years teaching: 13

"I am frustrated when my educated classroom choices are not respected by the public."

Donicht said the laws, amendments, and bills that are introduced and even passed make him feel like legislators think teachers "don't know what we're doing, we're inept, we're uneducated." Teachers are trained professionals and many hold a master's degree, he said. Instead, people who might be uneducated themselves are making decisions without giving teachers a voice. But it's not just legislators who make teachers feel disrespected or distrusted — parents and the general public do, too.

"The pandemic highlighted the importance of teachers, but once we came back in person ... that rhetoric changed," Donicht said.

"So many teachers are walking on eggshells right now, worried about what they're teaching, what they say, the interactions they have ... that is a real thing."

Donicht said books bans and challenges are stressful for English teachers especially. He is disturbed by the notion of books being pulled from shelves due to concerns from parents or patrons who have never read them.

"Just having that loom over a teacher (is scary)," he said.

Donicht said he takes pride in carefully choosing the novels to suit the specific students in each class, and said it's important for teachers to have that agency.

"I don't quit. That's not even a word in my vocabulary."

"Why am I committed to staying? Because I think I can."

Despite the challenges of teaching, Donicht foresees himself staying in the classroom until retirement. He said he is motivated to keep teaching partly out of gratitude for the teachers he had when he was growing up.

"I was blessed and lucky to have great teachers ... each inspired me to do the things I wanted to do, and it's a lot of the reason I'm doing this job. I truly believe in the power that a teacher has in the life of a kid," he said.

He also wants to stick around to instill in students a passion for learning and set an example of doggedness.

"I don't quit. That's not even a word in my vocabulary," he said. "I feel like I have what it takes -- the tough skin."

/

Caitlin Pankau

Pocatello High

Pocatello/Chubbuck School District

English, speech teacher

Years teaching: 11

"I want to be critical of (education) so it can change to be better, because it can be better."

She wants to see pro-education politicians — who talk to teachers — elected. Conversations would solve many of today's educational issues, Pankau said, as long as they're followed by action.

"It irks me because we always talk about things but nothing ever changes."

She wishes a legislator would come to her classroom — a common wish among educators. It's important for senators and representatives to see what their policies look like when they're implemented.

Conversations between teachers and parents are just as important. "Talk to us. Please talk to us," Pankau said. "Our lives are dedicated to ... helping your kid be the best version of themselves. We're here for them."

"Teaching is what I am meant to do with my life — my heart and soul are connected to this."

"My feelings (about teaching) haven’t changed, so to speak, just my understanding of the profession and what it all entails has clarified. Teaching has always been political, as everything (pay, laws, regulations, bell schedule, etc) is decided by the legislature or the school board; however, education has recently become a lot more partisan. This has lead to division, distrust, and miscommunication (and quite frankly, the passing of absurd laws and policies that inhibit teachers and students)."

Pankau said she plans to remain a teacher even though the profession is difficult -- she loves it too much to walk away.

"We're educated, we're dedicated, and we're here for a reason ... We should be trusted and we're not."

Pankau said it's been exhausting to slowly watch teachers' autonomy disappear and decay. Teachers are faced with more expectations and less respect each year, and are being asked to justify and explain all their choices in the classroom. On top of that, teachers must endure accusations that they're indoctrinating children. There's already a need for more diverse representation in English curriculum, but the political climate has made teachers afraid to use books that feature marginalized groups.

Certain bills, like HB 377, had a chilling effect on classrooms, Pankau said. It stopped some teachers from having critical conversations about race, sexuality, and history in the classroom because they were afraid to be persecuted.

"It's fear-mongering," she said. "What happens in our past makes us who we are today ... Whether we talk about it or not, it's there -- it's the elephant in the room."

Cori Morey

Meridian Middle

West Ada School District

Science teacher

Years teaching: 10; resigned in 2022

"I gained 80 pounds in the last few years, developed a left eye twitch, had high cortisol levels, and was catching (every bug) that came along ... I finally reached my breaking point last spring."

After ten years a a teacher, Cori Morey resigned at the end of the 2021-2022 school year. Her mental and physical health were suffering, so she decided to prioritize herself and her family.

"I felt like my foundation was just shaking — like I'd been shaken to the core of who I was."

After spending five years in college preparing to teach and then ten years in the classroom, Morey felt like she'd thrown her life into teaching and it was tied to her identity. When she decided to leave the profession, she told a counselor that she felt like her foundation was shaking. "You're still steady," the counselor told her. "You're just shaking away some of the outside layers."

Morey resigned in April (though she stayed to finish out the school year) and said it felt like a huge load had been lifted off her shoulders. "I have not regretted it since," she said.

When she resigned, her colleagues were supportive and many said they were thinking about leaving too.

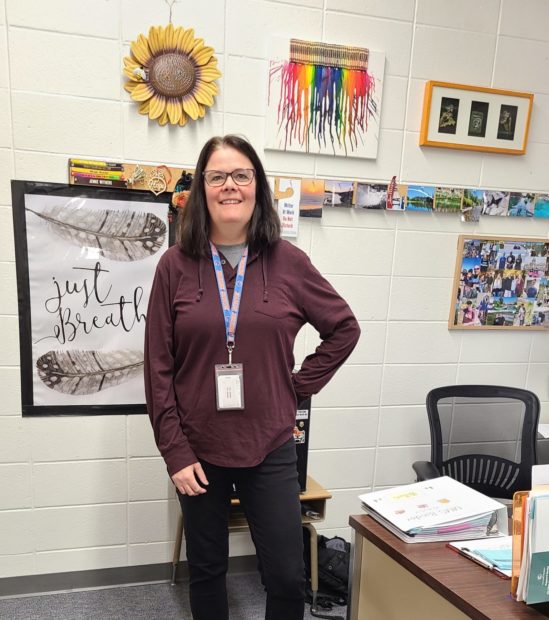

Jennie Withers

Meridian Middle

West Ada School District

English teacher

Years teaching: 25

"We are set up for failure on a daily basis ... and because we are failing we have lost all the respect."

Withers said she's frustrated with the way schools are funded. Districts are dependent on levies to bankroll "everyday operations" instead of extras as they were intended. Furthermore, districts receive funding for teachers' salaries based on how many students are enrolled rather than on student need. Today's students are still trying to recover learning lost during the pandemic, so more teachers are needed.

"We don't have a voice and we don't feel like we're respected at all," Withers said. "The way that we're funded shows disrespect."

On top of that, Withers said class sizes are too big -- sometimes climbing up to 40 students. A third of that class might have special needs and require extra attention from the teacher, who just cannot succeed in that scenario.

Student behavior is also worse than it's even been.

"In 25 years, I've never seen discipline issues like this," Withers said. "The message the kids are getting is you can treat your teacher however you would like."

"Our schools are falling apart."

Withers said her classroom hasn't been painted for more than 20 years.

"I have invested hundreds of dollars to cover up holes, black marks, and everything else," she said.

Meridian Middle School's campus has a main building and several outbuildings. The main building gets regular upgrades — like new floors and fresh paint — but the other buildings do not.

Withers said she has one colleague who had a crack in her wall that was so large she could see outside. That classroom had to be fumigated twice for spiders.

The day Withers spoke with EdNews in late September, she said there were wasps in the boys' bathroom due to another large crack.

"Students say this is the ghetto school," Withers said. "That's how they feel about it and treat it."

Deanna Carter

Sawtooth Elementary

Twin Falls School District

Kindergarten teacher

Years teaching: 17

"More and more and more is being added to our plates and nothing is being taken away. Soon the plate will break due to the stress placed upon it."

Already this school year, one of Carter's fellow kindergarten teachers quit. Carter was afraid that she would have to take on extra duties and students, but the district fortunately was able to hire another teacher.

"There is too much pressure put on teachers from administrators and parents and not enough support and help from them," Carter said.

"I love teaching. I love my students. I am a great teacher. But I cannot go through another year like I have the past two years that have been so difficult in every way — emotionally, professionally, physically."

In 2021-22, teachers were hopeful that things would be "back to normal" after the prior school years were beset with complications from COVID-19. But teachers were devastated when that hope was dashed, Carter said. Students that year were more difficult to manage than in any other way -- behaviorally, socially, and academically.

"They did not know how to act and it showed," Carter said. "It was unreal."

When her kindergarteners threw items at her or laid screaming on the floor, she tried to remember that the five-year olds had spent two years of their short lives shut up in houses and tucked away from society.

It wasn't just the kids. Parents were less engaged and more likely to blame teachers for any issues. And administrators were overwhelmed.

Nick Forbes

Notus Schools

Teach for America

Science teacher

Years teaching: 1

"It's about the moment where you can make a kid's day. "

Teaching is gratifying, enjoyable, and important. Forbes is in his second year as a teacher, and said he loves being a positive influence on kids and sharing his passion for science.

He's been most surprised by everything that goes into teaching behind the scenes: "the time, the effort, the planning, everything that you do with all the other teachers to ensure that kids are able to be successful."

Forbes said as a student, he only saw the tip of the iceberg. He also compared teaching to a "fully-operational death star." There are so many interconnected pieces working together to make education possible that so many people don't see.

He teaches in the junior/senior high school most of the day, but runs over to the elementary to teach a second period science class. A sixth grade teaching position went unfilled, so he and other coworkers have taken a piecemeal approach to filling it.

"It almost feels angry -- some of the political climate around education -- in a way that I'm somewhat confused by ... It's very different from where I grew up. "

A Teach for America educator, Forbes hails from Cleveland, Ohio. He's been taken aback by Idaho politics.

"There seems to be some anti-education perspective in a way that I don't feel like really makes much sense."

He's also been caught off guard by the amount of four-day schools in Idaho. Where he grew up, he said the idea of a four-day week "was so very foreign."

That said, he plans to stay in Idaho and continue teaching even after his two-year TFA stint is up.

"It feels like I'm doing something that matters."

Trisha Jernigan

Rocky Mountain High School

West Ada School District

Special education teacher

Years teaching: 25

"I was in the ER last week and they had to shock my heart ... Now I'm on heart medications ... I think it's because of all the stress and anxiety from teaching."

Every night that week, Jernigan's heart was racing. One evening, it was at 180 BPM for 14 hours. That's when she went to the emergency department. They shocked her heart to get it functioning properly. At age 47, Jernigan said she shouldn't be having heart problems. She attributes it to the stresses of her job.

The morning after her hospitalization, she still reported to work because there weren't enough subs to cover her classes.

Jernigan said she loves the kids, loves her job, and loves her colleagues. But the past few years have been some of the most trying she's ever had in 25 years of teaching. She works with the most high-needs students, who need to be hand-fed, lifted into standing and sitting positions, and diaper-changed. She said she's in desperate need of more aides, but she's afraid she'll lose the help she does have due to budget cuts. She's asked a certain question far too often: how can you make do with less?

As a special education teacher, Jernigan also has mountains of paperwork to complete. She arrives at work by 6 a.m. every day (an hour before class starts), and wants to start trying to go in at 5 a.m. two days a week.

"It just has to be done," she said.

Jernigan said she would "hate to not be a teacher," but she doesn't know if she can keep going physically and mentally.

"I'm just worried that less and less people are going to go into (teaching)."

There was a time when Jernigan's students would aspire to become teachers, but those days are no longer. Kids aren't talking about wanting to be teachers anymore.

Even her own daughter, who once planned to go into the field, has opted out. Watching her mother, she's seen what it entails all too closely.

"It's really sad," Jernigan said.

Scott Traverse

Woodland Middle School

Coeur d'Alene School District

Social studies teacher

Years teaching: 26

"I'll hang on for two reasons: 1) I still love teaching. 2) I have to because of PERSI."

After decades in the classroom, Traverse has taught multiple generations -- he now has former students' children in class. He loves that, and loves to run into 40-year-old alumnus at the grocery store who still recall memorable lessons from his class.

And he loves that his middle schoolers can understand why inflation happens -- and they're interested in it. If he can get them to groan because the bell rings and class is over -- that's the best.

So even as he watches colleagues filter into other professions, he's here to stay.

But it's not just his passion that keeps him around. PERSI - or "the golden handcuffs" as some teachers call the state retirement plan -- will keep him in the classroom until he can fully retire in five and a half years.

"If politicians came in and didn't stay for a half hour, but for a week, there'd be an apology letter and a thank you letter."

If legislators would come to his class, maybe they'd understand that "students are humans and not numbers or test scores," Traverse said.

District-level administrators also need to visit classrooms once in a while and "get their feet wet and their elbows dirty and work with us."

Traverse is certain that a window into teachers' lives would spark more appreciation, respect, and recognition -- which is needed to "counteract the stuff that's been happening for several years now."

And if parents thanked teachers more often and refrained from bashing them on social media, that would help too.

Shari Walbom

Nezperce Elementary

Nezperce School District

Fourth Grade Teacher

Years teaching: 15

"I will not stay with teaching. As much as I love being with the kids and teaching the kids, it's so stressful and I'm just over it."

Walbom has wanted to become a teacher since she was a child -- it was a calling. But at the end of a recent school day, she said she couldn't do it anymore. Just that day, she didn't get a lunch or a prep period because she was helping students, in meetings, or running extracurricular activities. On top of that, there's a lack of administrative support, disrespectful children, and not enough paraprofessionals. And a substitute teacher shortage means the school's existing staff gets spread especially thin when the principal or a parapro has to abandon their typical duties to cover a class.

"It's kind of a tightrope," Walbom said.

Walbom said she'll teach through the end of this school year, but hopes to have another job lined up by then.

"I don't have time to teach your kid manners — I want to teach them math."

"Our society has an under-parenting problem," Walbom said.

She said parents are relying on teachers to "fix" their children's social and behavioral problems. Students are coming into classrooms less prepared -- academically, socially, and emotionally -- than ever before. It's placed even more burdens on teachers, and Walbom said it's too much.

"I can't be a psychiatrist and a mom and a teacher and a loving grandma all in the same room," she said. "I don't have have time for that."

Tracey Cook

Skyview High

Nampa School District

Biology teacher

Years teaching: 27

"Teaching is a fulfilling job and interacting with students gives me energy."

Cook is one of the many Idaho teachers who, despite an array of challenges, still finds satisfaction in her job every day.

A recent EdNews survey shows that most Idaho teachers, 52%, report feeling satisfied with their jobs.

Many are struggling, but many are also flourishing.

But satisfaction doesn't just happen, Cook insists. It takes work — and a certain mindset.

That includes realizing that some things are simply out of your control as a teacher. Focusing on the things that you can control is crucial to surviving, said Cook. That includes time spent teaching in your own classroom, with your own students.

"There are non-negotiables, but I have control over most things."

Of course, there are things teachers have to do, including administering state tests, building lessons around state learning standards and adhering to the long list of state and federal laws.

And though Cook said she has less autonomy than she did when she started teaching, she still has control over a lot.

"You have to learn to navigate changes by focusing on what you can control and what works," she said.

Living up to the advice she gives to stay positive is also important. She pointed to the pandemic's assault on in-person learning the last two school years.

Students forced to stay home. Teachers forced to teach remotely.

While COVID was challenging, it was also "a reprieve and a chance to expand my teaching platforms," Cook said, pointing to her improved understanding of Microsoft Office, Teams and other platforms that she didn't know much about before being forced to teach remotely.

Wallace Blacker

Murtaugh High

Murtaugh School District

Science teacher

Years teaching: 30; retired in 2022

"Equity (for Idaho's veteran teachers) just isn't there."

Blacker, 58, said he made efforts to square his pay with his sense of worth over the years, from staying in the classroom for three decades and earning his master's degree to going the extra mile in 1997 to garner recognition from then-Gov. Jim Risch as a notable Idaho science teacher.

But the things he thought would help only made him feel less valued in the end, he said.

Despite "busting my butt," Blacker said, he didn't feel the sense of worth he'd hoped for as a veteran teacher. He recalled a recent pay comparison with his daughter, a fellow teacher. She was a third-year teacher in a neighboring district of similar size to his and had an annual salary of $46,000. He was making just $7,000 more than her.

Blacker acknowledged big-money efforts to raise pay for Idaho teachers in recent years. The state's average teacher salary hit an all-time high last year, coming in at $53,100 following years of investments from the state.

But for Blacker, much of the effort was flawed. He pointed to the emphasis Idaho's career ladder salary law has had on pushing raises to younger teachers like his daughter — an effort to bolster Idaho's pipeline of educators.

And the Legislature's "master educator" premiums, a $4,000 per year bonus that, up until last year, were designed to reward Idaho's highest performing veteran teachers, didn't do it for Blacker. The premiums renewed for three years, bringing their total value for a successful applicant to $12,000 unless they stop teaching.

Blacker called them "dangling carrot."

"A dangling carrot wasn't enough for me."

And he wasn't alone in his distaste for the premiums. At one point, state officials estimated 8,000 to 10,000 teachers would meet the eligibility criteria. But thousands of teachers, including Blacker and some of Idaho’s most decorated, did not even apply.