Often overlooked or marginalized as early migrant workers, Hispanic families — increasingly integral to Idaho’s skilled and educated workforce — value education as a means to success and as a privilege.

“When we first got here, I was a single parent and my son had to work. He went to the field for four months, and he’s like, ‘Mom, I can’t do this.’ I told him you need to finish school so you get a better job. Because only jobs like this will hire you on the spot. Even McDonald’s these days, you need at least a GED. You want to work in this all your life? Being in the sun? Being dehydrated, not eating well, for so many hours? It was a hard lesson for him, but now he knows. He’s back in school,” a parent from Payette told education researchers.

Bluum, a nonprofit that supports charter school growth and school improvement, funded focus groups with Hispanic families in Idaho. It set out to learn more about the experiences of Hispanic parents around their education hopes, concerns and opportunities.

The Farkas Duffett Research Group hosted five focus groups with 45 Hispanic parents whose children attend school in Idaho Falls, Payette, Twin Falls, Nampa and Caldwell.

The Hispanic presence is becoming increasingly important. According to Pew Research Center, “Hispanics have played a major role in driving U.S. population growth over the past decade. The U.S. population grew by 23.1 million from 2010 to 2021, and Hispanics accounted for 52% of this increase — a greater share than any other racial or ethnic group.”

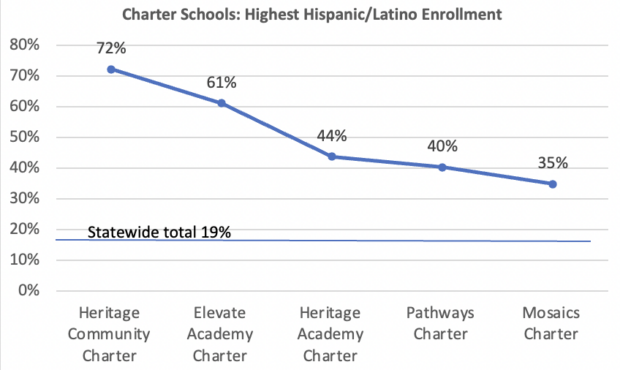

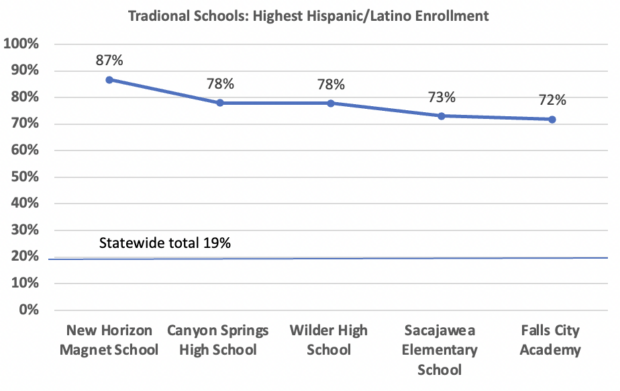

Here in Idaho, that trend is consistent: the fastest-growing student demographic is Hispanic students. They made up 18% of K-12 enrollment in 2019-20 (about 56,000 students) and they accounted for 31% of enrollment growth in the previous five years, according to the report Here to Stay: Hispanic Parents talk about Schools and Life in Idaho.

Two topics resonated from the focus groups of parents: improve communication and avoid making assumptions based on race. Parents want direct and personal conversations with educators. And placing a student into an English as a second language (ESL) program cannot be simply based upon one’s ethnicity, the report said.

“They have so many platforms…They have four different places that you can go and get this information for homework, grades, attendance, but there’s four different places instead of one place. It’s the same kid. They have PowerSchool, they have Parents Square, they have Otis,” said a Nampa parent.

More Spanish-speaking staff could open the door to better communication

Hispanic parents liked the idea of seeing Hispanic staff or having Spanish-speakers on staff, the report said.

That’s a problem in Idaho. According to the most recent Idaho Commission on Hispanic Affairs report, Hispanic administrators, teachers and staff made up 3% (about 550) of all employees in 2020, while Hispanic students made up 18% of K-12 enrollment. Teachers represented the largest number of employees (495), followed by school counselors (20), principals (12) and assistant principals (10). There were three speech pathologists and three school nurses but no superintendents.

According to the report, some parents thought it would be useful to have Spanish speakers so that they could communicate with new parents whose primary language is Spanish. And many said that it could be reassuring to see “a teacher that looked like me.”

- “When you walk in, if you don’t see somebody that looks like you, you might feel a little bit like an outsider. When I first came to this school a couple years ago, I didn’t see a lot of Mexican-looking kids. I didn’t know how my kids were going to make friends. But it worked out. We made a decision. It’s not all going to be based on what the people look like. If it’s full of Mexicans but they’re all bad teachers, I wouldn’t want my kids there. We’d still go through the steps to get to know the teachers, see how they work, see how the kids do in that school. It’s not all going to be based on what the people look like,” an Idaho Falls parent said.

- “I went to school here years ago and there were only five Hispanics and I literally felt left out… So that’s a very sensitive subject for me because I experienced that and I don’t want my kids to experience that,” a Nampa parent said.

Teaching Spanish to their children is primarily the family’s responsibility

While Hispanic parents want their children to speak Spanish — it’s a helpful workplace skill and important for maintaining family contacts — many said it’s the family’s responsibility, not the school’s, according to the report.

- “We’re very strictly Spanish at the house. It would be cool to see our kids come into school and just go over things, reinforce it a little bit. But that’s not our main concern. Because even when they bring homework to us and they want help, if it’s in English, we’ll read it to them in Spanish and they have to answer in Spanish. And that’s just the way we do it. At school, they could learn Chinese or German or something,” an Idaho Falls parent said.

- “I want the teachers to focus on English. If my son’s not getting it in English, then he’s not going to get it in Spanish. Focus on one language with him. We’ll work out the Spanish at home. I say it from experience. My Spanish is not a hundred percent proper. At my job, it doesn’t need to be exactly proper. When you talk to another Hispanic, their Spanish is not going to be proper either,” a Nampa parent said.

“It’s not their responsibility — it’s ours. If we want our kids to learn a second language like Spanish, because that’s what we know, then you have to teach your kids at home,” an Idaho Falls parent said.

Assumptions about language fluency place students in unnecessary programs

The report advised schools to avoid making assumptions about English fluency. English-speaking parents who don’t understand Spanish complained about receiving emails written in Spanish. More serious problems were caused when English-speaking children were placed into ESL classes based solely on surnames, the report said.

- “They took him out of regular classes to a class with just kids that were learning English. And they didn’t notify us as parents. We were having dinner one night and he brought it up and I’m like, ‘Wait a minute, they took you out of class?’ So I approached the school on it and they couldn’t give me an explanation. And I said, ‘Is it just because of his last name?’ And they said, ‘Well, we just felt like it would be a good fit for him.’ And I said, ‘No, I don’t want my son taken out of regular classes into ESL when he speaks English just fine. If I hear that he’s being taken out again, then I’m going to come back and we’re going to have some issues.’ And it stopped,” an Idaho Falls parent said.

- “They send out these mass emails and we always get them in Spanish and I can’t ever understand them. So I went to the school one day and I said, ‘Hey, can you send them to me in English? I’m not understanding these Spanish ones that you’re sending out.’ And they stopped for a while and then this year they started again sending them in Spanish,” a Twin Falls parent said.

Schools are slow to diagnose learning disabilities

The challenges faced by parents of children with learning disabilities had an added layer of complexity. Several who were U.S.-born complained that the schools failed to recognize a child’s learning disability in a timely manner because they wrongly assumed that learning English was the problem, the report said.

- “When I was getting my son tested, we didn’t really know if he had autism or a learning delay or what, but the district said sometimes there can be a six-month delay where the child doesn’t understand because you taught him Spanish. But my son spoke English. I kind of took offense to that. I knew as his mom that he was behind in both languages. But the school wasn’t seeing that, right? And eventually, we figured out that yeah, he was delayed — in both languages, he was delayed. Maybe it’s just a lack of cultural awareness on the school’s part. I felt like my son was looked down upon,” a Twin Falls parent said.

- “We were kind of treated like second-class citizens when my son first got tested for speech and stuff. I mean his therapists are amazing. But at first they looked at me and they just assumed you speak Spanish at home. My husband doesn’t even speak Spanish. And they would dumb stuff down for me because they felt like I wasn’t going to understand it if they used the proper terms. And it was like they just assumed that I was an uneducated Mexican,” an Idaho Falls parent said.

Communication with parents should be responsive and focus on what’s important

Parents expressed dissatisfaction with the way schools communicate: being ignored or brushed off when engaging about their children’s academic or social problems. Others complained that the schools were better at updating logistics and procedures, rather than academic progress. And the number of communication platforms make it hard for parents to monitor academics, according to the report.

“The reliance on technology is adding noise rather than clarity to communication,” the report said.

- “If I have a concern, they just disregard it. I don’t feel like I get answers from them. I want to transfer him to a different school. Just because I believe that there’s bullying happening, because he showed up with his broken glasses. He said that it was an accident, but it’s been too many occurrences. And I addressed the school, and the principal, they’re like, ‘We’ll get back to you. We’ll get back to you.’ And I got no response,” a Twin Falls parent said.

- “They have so many platforms…They have four different places that you can go and get this information for homework, grades, attendance, but there’s four different places instead of one place. It’s the same kid. They have PowerSchool, they have Parents Square, they have Otis,” said a Nampa parent.

- “He really struggled with the social piece. The teacher would send pictures of the kids doing something on Class Dojo and my son was never in the pictures or he was in the background. I would ask and she would never give me feedback. And my son, of course, doesn’t say much, so he can’t really tell me. But I had to really dig, I had to basically say, ‘Hey listen, I noticed that when you send pictures my son’s never sitting, or my son’s never doing what the class is doing.’ And she finally said, ‘Oh well, if he doesn’t feel like participating, I just let him go play.’ I would like to know that, as a parent, that my son’s not participating, and you’re not figuring out a way to get him involved or to get him the help. I’ve seen a big difference in the new school, he doesn’t have that problem anymore,” an Idaho Falls parent said.

Farkas suggested schools revisit communications procedures. “Rather than adding more, I’d advise understanding why what they’re doing now is sometimes off the mark and doing it better,” he said.

Schools could help Hispanics be more aware of college financial opportunities

Hispanic parents have a non-negotiable attitude about the importance of college, saying that they drill this expectation into their children’s heads. Others emphasize learning a skilled trade, seeing it as the key to good-paying jobs and self-sufficiency, the report said.

They need to hear that college is more affordable than they might think. They need reassurance that financial aid may result in less student loan debt than imagined, the report said.

Farkas said, “The availability of decent jobs is tough competition when college is seen as so expensive. But headlines about student debt can be countered by direct, personal outreach from trusted educators in the schools. Sometimes a standout story about an individual student in the school who received a free ride to a four-year college can break through people’s consciousness.”

- “I think it’s a stereotype that us as Hispanics don’t really focus on education, and don’t really focus on our children going to college. I could see this being more true of my mother. But this generation… As a Hispanic, I see more people my age wanting our kids to go to college. Back in the day it was more like, you just got to work,” an Idaho Falls parent said.

- I want them to be independent and to be able to support themselves and not depend on anyone else. And not to be working in the fields and not to be living check to check for the rest of their life. It doesn’t have to be college. It can be a trade school, it can be hands-on, it can be military, it can be anything that they choose to do. But sometimes, if you don’t have that degree, if you don’t have that certification, they’re not going to pay you,” a Nampa parent said.

- “It’s crazy expensive and then they have this debt. It’s crazy. Maybe he wants to go to college to learn whatever. I feel like I just want him to explore his talent, his skills, into something that makes him successful, independent, responsible, a good man,” a Nampa parent said.

The direction of the focus groups flowed into their sense of place in Idaho — how Hispanic Idahoans see themselves, how non-Hispanic Idahoans see them and how things have changed over time. “Idaho’s Hispanics are members of a demographic group that continues to find its voice. They have changed, Idaho has changed, and both are still changing,” the report concluded.

Disclosure: Idaho Education News and Bluum are funded by grants from the J.A. and Kathryn Albertson Family Foundation.