SUGAR CITY — Alan Dunn pulled his white Lincoln sedan onto Center Street in Sugar City.

A quarter mile of mostly quintessential, Main Street America rolled into view.

The post office to the left. The gas station from the 1950s to the right. The mom-and-pop hardware store in operation since World War I further up the street.

But the 6-foot-4-inch superintendent of the Sugar-Salem School District wasn’t driving around the small town surrounded by a sea of potato fields just to take in the view.

“There’s hardly any business here,” said Dunn, passing the local grocery store, long since closed down. A bygone convenience store with boards for windows sat to the right. “It’s really tough.”

Sugar City’s bout to attract and retain businesses runs a deep thread in the heavily Mormon, Eastern Idaho farming community. It’s a decades-long struggle that has found Dunn wincing at Sugar-Salem’s recurring place at the bottom of statewide property tax valuations.

Average daily student attendance remains the main yardstick used to carve up the state’s portion of K-12 funding. Still, taxes levied on local businesses and housing account for a growing amount of money school districts use to increase teacher salaries, build infrastructure and supplement other budgets — even as the state picks up a greater share of K-12 funding. As a result, school administrators are often the first to know when local business is good or bad, or when communities are growing or stagnating.

But wide gaps in market values enable some school districts to tap into much more substantial tax bases. And disparities in funding, per-pupil expenditures and teacher salaries sometimes show for it. As a result, Dunn said his district’s plight for local dollars has created a hodgepodge of problems, from troubled labor negotiations to crumbling and aging buildings to hiring uncertified staff members.

In the 2017 “People’s Perspective,” a public opinion poll conducted by Idaho Education News, most Idahoans said they want more equity in their schools. Of the 1,004 Idahoans surveyed, 75 percent said it’s the state’s responsibility to make up the differences between poorer and wealthier districts.

Dunn praised lawmakers for recent upticks in statewide K-12 funding, but said Idaho is a long way from leveling the playing field.

“The gap between rich and poor districts really has a lot do with where your school district is located,” Dunn said.

Sugar-Salem: A rich industrial history, a meager tax base

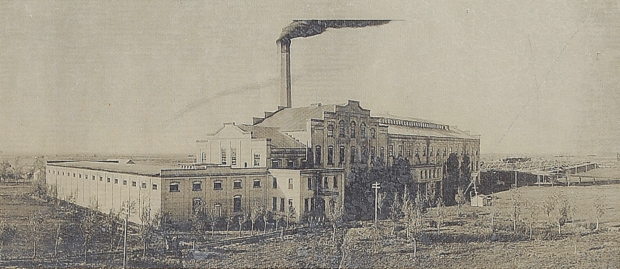

A walk out the front doors of Sugar-Salem’s Kershaw Intermediate School provides a glimpse into Sugar City’s hulking industrial past. Across the street from the school, in a field now teeming with weeds, lies the town’s namesake sugar factory — or what’s left of it.

Built in 1904, the factory was once central to the birth and rise of Sugar City. A portion of it still stands as a looming reminder of what once was.

“At the time, it was the largest sugar factory in the U.S.,” reads a weathered wooden monument in front of what’s left of the original structure — a yellowish, 250-foot-long vacant sugar storage holding.

During its nearly four decades of operation, the factory brought hundreds of residents into Sugar City and pumped out some 405,000 tons of sweetness, extracted from millions of sugar beets pulled from surrounding fields.

But technological advancements in sugar extraction and area farmers’ growing bent toward potatoes forced the factory’s closure in 1942.

“We sort of just fell off the face of the earth when that factory closed,” said Sugar-Salem Junior High principal Kevin Schultz.

Sugar City never regained its place as an industrial hotbed in Eastern Idaho, but today the town touts a variety of local businesses: a nearby Wal-Mart, downtown hardware store, service station, car wash, restaurant, detail shop, beauty salon, dentist’s office, dance studio and two potato processors. Over the years, growth in nearby and booming Rexburg has also buoyed Sugar-Salem’s population and property values.

But it hasn’t been enough to lift Sugar-Salem onto the same financial plane as other school districts its size in Idaho. When divided by average daily attendance, Sugar-Salem’s 2016-17 market value ranks lowest in Idaho, at $173,706 per student. (Click here to see how your district stacks up in terms of ADA-based market values.)

To put that number into perspective, the similarly sized West Bonner County district has a market value almost 10 times that of Sugar-Salem’s.

By the numbers: Sugar-Salem’s math problem

A side-by-side comparison of district funding and revenue sources sheds light on the financial disparity:

District market values, divided by average daily attendance

- McCall-Donnelly (1,053 students): $2,899,242 per student.

- West Bonner County (1,044 students): $1,625,607 per student.

- Bear Lake County (1,125 students): $727,747 per student.

- Filer (1,572 students): $304,148 per student.

- Payette (1,451 students): $259,439 per student.

- Sugar-Salem (1,536 students): $173,706 per student.

- State average: $808,517 per student.

District funding, by revenue source

- Sugar-Salem: State, 92.4 percent; local, 5.1 percent; federal, 2.5 percent.

- West Bonner County: State, 62 percent; local, 31.6 percent; federal, 6.4 percent.

Funding via local tax levies

- Sugar-Salem: $450,000.

- West Bonner County: $3.1 million.

Local levy funding per student

- Sugar-Salem: $298.

- West Bonner County: $2,793.

Local revenues affect district spending. West Bonner County’s overall per-pupil expenditures for 2015-16 were $8,846, compared to Sugar-Salem’s $5,847.

And while several factors, including experience, can affect teacher salaries, the comparison between Sugar-Salem and West Bonner County illustrates a teacher pay gap. Sugar-Salem’s average 2016-17 teacher salary is $40,039, compared to West Bonner’s $45,806. The statewide average comes in at $46,439.

A salary dilemma

While 93 school districts have a supplemental levy on the books, some choose not to seek help from local taxpayers.

“It would be nice to have a levy,” said Andrea Schaeffer, the Dietrich School District’s business manager. “But it’s one of those things that you can’t always ask patrons for, especially if they don’t have the money.”

Dietrich’s ADA-based market value is $231,095 — higher than Sugar-Salem, but ranked No. 104 among Idaho’s 115 school districts.

From Bruneau-Grand View and Glenns Ferry to Wilder and Lapwai, some poorer districts have seen levies fall short of the majority needed to pass.

Sugar-Salem is mindful of its tax burden on patrons, Dunn said. Partly in response to state funding increases, the district decided to cut back on the supplemental levy it will seek in Tuesday’s election. The district is asking for $400,000 over two years, down from a $450,000-a-year levy.

Sugar-Salem’s current levy helps the district bolster parts of its budget, said Rep. Wendy Horman, R-Idaho Falls.

“(Sugar-Salem’s) teacher salaries might not be the highest, but remember, they also provide health coverage for teachers and their families,” Horman said. “Many districts don’t offer that.”

Dunn said the funding disparity still takes its toll, especially when it comes to salaries. Last year, a contract negotiations deadlock dragged into October. Eight of Sugar-Salem’s 80 certified employees are working on a provisional certified basis. One employee does not even possess a college degree.

“It’s really difficult to get people here,” said Dunn. “So we sometimes have to hire them on a provisional basis.”

But a $400,000 miscalculation on the district’s part also contributed to the 2016-17 negotiations deadlock. And $25,000 in pay raises for administrators — including an 8.84 percent bump for Dunn himself — had some teachers questioning the severity of the district’s purported financial hardships mid-negotiations.

A facilities dilemma

A small tax base also makes it difficult to upgrade and build new infrastructure to keep up with a growing student body. Dunn pointed to an old automotive shop across the street from the district office in downtown Sugar City.

“I get nervous having any of our people even go in there,” Dunn said.

The district shop, built around 1900, houses a variety of equipment, from mowers to maintenance trucks. But the wall on the west side of the building has buckled slightly near the top — a telltale sign of pending collapse. The building’s disrepair last year prompted one local business, ProPEAT, to donate two acres for the district to build a new storage shop. The district took advantage of the offer, budgeting $100,000 for a new shop. But those funds dried up before the building was finished, Dunn said, so the district stalled construction early.

“What school district has to build a shop and then stop before lights and electricity are added?” Dunn said. The shop has sat vacant and unused for months.

School construction is also done on a piecemeal basis in Sugar-Salem, Dunn said, because the district cannot bond for new facilities in one swipe. Idaho law caps school bond measures at 5 percent of a district’s total market value. In Sugar-Salem’s case, the number settles at just over $13 million. To avoid a property tax hike, the district floated a $5.5 million bond issue in 2012, which received a supermajority of support from patrons. The district hopes to pass a nearly identical bond issue on May 16 in order to begin funding construction of a new junior high school — over 15 to 20 years.

“We’ll start with a new multipurpose room,” Dunn said. “Then five years later, we hope to run a bond again and add some classrooms. Five years after that, we plan to add an upper level.”

The district has $526,000 in its capital projects fund. Out of that amount, said business manager Becky Bates, $162,000 is slated for projects this summer — including, perhaps, adding electricity and lights to the vacant shop. Trustees will be able to use the remaining $364,000 on other projects, she said.

Sugar-Salem isn’t the only district that’s struggled to upgrade infrastructure. In 2013, the state swooped in to bankroll $3.6 million in repairs to two aging schools in the Salmon School District, after local voters rejected building bond issues nine times over eight years.

A question of equity

Horman acknowledged that one district’s tax base can generate “much more” revenue than another district’s base, but stopped short of calling the funding gaps inequitable.

Horman pointed to Idaho’s bond-levy equalization fund, which uses state dollars to help relieve school districts of their interest payments on school bonds. This fund should cover around 29 percent of Sugar-Salem’s current $5.5 million bond issue, Bates said.

A section of Idaho’s Constitution says “it shall be the duty of the legislature of Idaho, to establish and maintain a general, uniform and thorough system of public, free common schools.” But Horman says this language is often misinterpreted; a 1993 Idaho Supreme Court ruling found that the Constitution requires “uniformity in curriculum, not in funding.”

“The court identified three areas as constituting ‘thorough’ — school facilities, instructional programs and transportation,” she added.

Horman, a member of the Legislature’s Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee, also cited recent increases in statewide K-12 spending. Districts’ ability to levy local taxes is the “ultimate local control,” she said, which gives them a chance to access more funds if and when they need it.

Like Horman, Sen. Janie Ward-Engelking sits on JFAC and a legislative committee charged with revamping Idaho’s complicated school funding formula. Ward-Engelking, D-Boise, said she’s all for more local control, but districts shouldn’t have to rely on local taxpayers.

“Forcing districts to rely on supplemental levies creates a system of haves and have-nots,” she said.

The burden of scrounging for local funds falls heaviest on rural districts such as Sugar-Salem, where farmers ride the ups and downs of markets and harvests.

“I think we are moving in the right direction with school funding overall, but the state needs to be doing more on its part,” she said.