Two months ago, a group of teenagers told leaders at the State Board of Education that mental health should be one of educators’ top priorities during the 2020 school year.

On Wednesday, the State Board of Education centered that topic in a 90-minute summit, where board president Debbie Critchfield asked mental health experts, counselors and representatives from state agencies about tangible ways Idaho can support students’ mental and emotional health.

Their recommendations focused on de-stigmatizing mental health, improving mental health awareness and communication among educators, and boosting access to professional help for students who need it.

“We need to set our students up for success,” College of Western Idaho student body president Lydia Shearman said in a video message recorded for the summit. “Leaving them high and dry because their issues are invisible is setting them up to fail.”

Alison Malmon, founder of a national program called Active Minds, started the summit with a keynote speech about changing the conversation around mental health.

Malmon’s brother took his own life 20 years ago, after struggling with schizoaffective disorder. He was a star student, and had suffered in silence for years before coming forward about his struggles with mental health, she said. Malmon, a college student at the time, recognized her peers weren’t talking about mental health either, largely because of the shame and stigma around mental health conditions. She launched Active Minds, a student organization now active on more than 800 high school and college campuses nationwide, as a way to normalize that conversation, so that students who are struggling “feel comfortable reaching out for the help they deserve.”

A majority of mental illnesses start to manifest in young people between the ages of 14 to 24, according to the Active Minds website. Nearly 90 percent of young adults reported experiencing stress or anxiety related to COVID-19 on an Active Minds survey in September, and one in four youth said the pandemic had increased their feelings of depression.

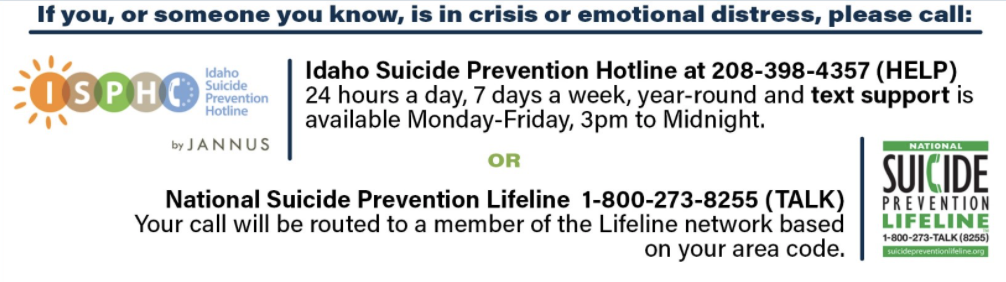

Changing school cultures to support student’s mental health needs takes everything from adding mental health units to health classes, adding mental health training to orientations, providing easy access to suicide prevention hotlines and other health services, and adequately staffing counseling centers with a diverse group that represents the student body, Malmon said. The goal is to make students feel like they have access to services, before they need them.

“Students are looking to their leaders to help support their mental health, not to ignore it,” Malmon said on Wednesday. “I can’t underscore this more: we need to show up for our young people.”

Students and state leaders told Critchfield they want more access to counselors, and collaboration between agencies and communities.

“We need to really pair training on mental health education… with the availability of the resources, so that when a student finally finds someone who will listen to them, and they get referred to help, that help is there,” said Rick Pongratz, director of counseling and testing at Idaho State University.

Chris Manley, president-elect of the Idaho School Counselor association and a counselor in the Boise School District, told Critchfield the state averages only one school counselor per 550 K-12 students.

“The case numbers in schools, they’re large, they’re overwhelming at times,” Manley said. “What would happen if that were to decrease, five to ten percent per year for the next five years?”

Carol Vanhoozer, who coordinates counseling services at the College of Southern Idaho, said the caseload there is more like one counselor to 2,000 students.

Vanhoozer told Critchfield she’d like to see renewed collaboration between universities who can share resources and best practices on mental health, similar to an Idaho College Health Coalition that was active in 2016.

Gov. Brad Little told panelists on Wednesday that he’s committed to pushing for resources and programs that will help address student’s mental and behavioral health needs. Last year, Little and State Superintendent Sherri Ybarra pushed the legislature to approve $1 million to support students’ social and emotional wellbeing.

Malmon said she’s encouraged by Idaho’s focus on student mental health as people young and old struggle with the physical and emotional toll of the pandemic.

Truly changing culture around mental health takes an ongoing commitment, she said.

“What is not a culture change is when we only talk about mental health during crisis, when we only talk about it after a suicide or in a pandemic,” she said.

“This is a really important time to start the conversation for folks who may not have been willing to be in it beforehand, but we cannot end it when the pandemic is behind us.”