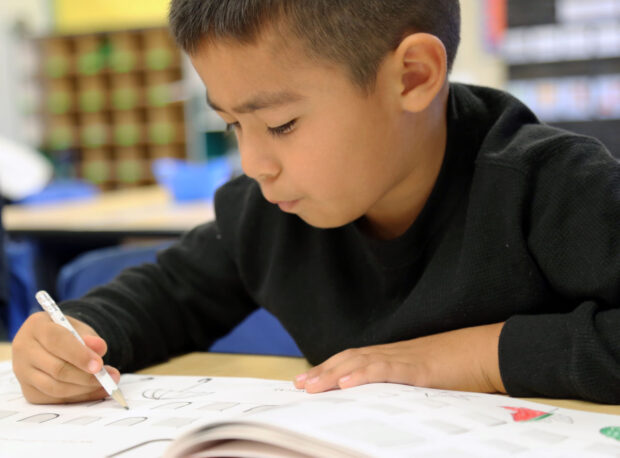

In Erika Carpenter’s second-grade class, a handful of students are working on the basics of reading. They are sounding out letters, one by one, in small words: real words and nonsense words alike.

Down the hall at Boise’s Koelsch Elementary School, kindergartners are working on similar drills. The second-graders are trying to catch up — and there is no way to rush them along. The best way to bridge the gap is through constant and time-consuming repetition.

Down the hall at Boise’s Koelsch Elementary School, kindergartners are working on similar drills. The second-graders are trying to catch up — and there is no way to rush them along. The best way to bridge the gap is through constant and time-consuming repetition.

Meanwhile, Idaho faces its own gap. Each fall, four of every 10 kindergarten through third-grade students show up for school unable to read at grade level. This year, Koelsch and other elementary schools are sharing $11.25 million in state money, earmarked to reading. It’s up to local educators to figure out how to spend their money — and how to address their schools’ unique challenges and demographics.

The problem, summarized

One startling number illustrates the size of Idaho’s literacy challenge: 36,904.

From 2013 through 2015, an average of 36,904 K-3 students scored below grade level on the fall Idaho Reading Indicator — a short screening exam designed to identify at-risk readers.

The IRI is a snapshot — and it doesn’t mean at-risk readers are hopelessly behind their classmates. In the spring of 2016, exactly 25,000 students scored below grade level on the IRI, down from 36,780 in the fall of 2015.

The end of third grade looms as a pivotal point in a student’s academic career. It is at this point that children go from learning to read to reading to learn. As students are expected to think more critically, their ability to comprehend class materials becomes paramount.

The end of third grade also represents a point of no return. Third-graders who struggle to read are unlikely to make up this gap — and as a consequence, they are less likely to succeed as their school career continues.

Which brings us to another set of important numbers.

On the spring 2016 IRI, 16,816 third-graders scored at grade level.

But 6,222 did not.

And that’s 27 percent of the state’s third-graders.

The plan, summarized

Education leaders and elected officials have long been aware of Idaho’s reading challenge.

But in 2016, the Legislature and Gov. Butch Otter agreed on a plan, and opened up the state’s checkbook.

They passed a literacy initiative that is designed to give more students extra help in reading — providing added time for repetition and drills in classes such as Carpenter’s.

For students who score “below basic,” the lowest of three levels on the IRI, this is supposed to translate to 60 hours of extra help during the year. This is an increase from the 40 hours of extra help available under old state law.

For students who receive a score of “basic” — the IRI’s middle score, but still below grade level — that means 30 hours of extra help, where none was available previously.

The added help comes with an added cost. The $11.25 million budget represents a $9.1 million increase.

Districts and charter schools get their share of the money based on the number of their students who scored below grade level on the IRI. This year, that comes to about $305 per student.

But beyond the 30- or 60-hour instruction time requirements, schools are free to craft their own reading plans. Every school is, in effect, a pilot school.

Depending on who you ask, that is one of the initiative’s strengths — or a weakness that could result in squandered taxpayer dollars.

Trial and error?

Boise will not roll out a centerpiece of its $831,000 literacy strategy until after the 2016-17 school year. The district will expand its summer school program, inviting all students who score below grade level on the IRI. The free half-day sessions will be available at four schools, and is one way to get students more hours of instruction in reading and other topics.

Boise and other districts are looking at ways to extend the school day, or the school year. Other districts are looking to add teachers or paraprofessionals to provide more intensive or small-group instruction. Other districts are spending their literacy dollars elsewhere, in hopes of making the most of students’ classroom time.

The Coeur d’Alene district is receiving $321,000, and its biggest line item is $118,000 for teacher training. Twin Falls is receiving $384,000, and its big-ticket item is a plan to spend $99,000 on Chromebooks and charging stations.

Experimentation is not only allowed. It’s encouraged. In a state where Otter, Superintendent of Public Instruction Sherri Ybarra and key legislators extol the virtues of local control, the literacy plan was written with that principle in mind.

Newly elected Boise school trustee Beth Oppenheimer is concerned by the scattershot approach. As a leading advocate for pre-K, and executive director of Idaho’s Association for the Education of Young Children, Oppenheimer also believes the state would be better off making cost-effective investments in preschool, instead of giving schools free rein and little guidance.

“I understand that districts need to do what districts can do,” she said. “But at the same time … kids learn the same in Weippe as they do in Rupert.”

Rep. Wendy Horman has mixed feelings as well. As a member of the Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee, and a lead writer of the committee’s K-12 budget bills, Horman will have a hand in what future literacy budgets look like.

“I believe in local control, but I also believe in using evidence-based approaches,” said Horman, R-Idaho Falls.

But the pilot plan still has a lot of powerful support — even if it entails some taxpayer-financed trial and error. Senate Education Committee Chairman Dean Mortimer likes the approach. So does new House Education Committee Chairwoman Julie VanOrden, an author of the new literacy laws. JFAC’s Senate co-chair, Shawn Keough, supports the block grant approach, but she expects the schools to deliver results in the end.

“If we’re going to believe at the state level in local control, we’re going to have to have some trust,” said Keough, R-Sandpoint.

Demographic challenges

At the start of the school year, only 39 percent of Koelsch’s kindergartners read at grade level — well below the statewide average of 51 percent, and the Boise district’s average of 63 percent. Located in an older, working-class neighborhood, Koelsch faces some daunting demographic challenges, especially when compared to the rest of the Boise district.

- Sixty-two percent of Koelsch’s 442 students fall below the federal poverty line; only two of Boise’s schools have a higher poverty rate.

- In 2015-16, 21 percent of Koelsch’s students had limited English skills. The district’s LEP population was 12.5 percent.

These demographic realities are not just academic. An Idaho Education News data analysis reveals statistically significant correlations between poverty, limited English skills and reading scores. Schools and districts with high poverty rates and high LEP populations tend to also have higher numbers of at-risk readers.

Koelsch’s teachers and administrators encounter these realities on a daily basis. Many students come in with limited vocabularies — a reflection of the fact that English is their second or third language. Engaging parents, and getting them to attend night meetings to discuss reading and math skills, requires a little bit of creativity.

“We always provide food,” principal Ken Pahlas said. “That gets a lot of them in here.”

The new literacy money is going to help, school officials say, but only to a point. It’s not enough to cover the cost of all-day kindergarten, one option under the law. And it simply isn’t realistic to expect many Koelsch parents to pay tuition for expanded kindergarten, reading specialist Loni Westrick said.

But Koelsch has some success to build on. The school’s IRI scores consistently improve from fall to spring, said Westrick — a sign of student growth and the result of quality instruction. In the fall of 2015, only 36 percent of kindergartners scored at grade level on the IRI. By spring, that number had zoomed to 89 percent. (Other grades showed improvement as well, although their spring proficiency rates came in at 59 to 65 percent.)

So the plan at Koelsch is much the same as it has been in the past. Persistent drilling and repetition. Watching for that surge in reading skills, a breakthrough that can occur at any time. And fine-tuning the learning plan on the fly.

If the teachers are doing their jobs right, Pahlas said, students will receive different instruction as the year unfolds.

It’s a lot of work, said Westrick. “But it’s the right work.”

Literacy series, at a glance

Wednesday: Idaho schools try to bridge a wide reading gap

Wednesday: A close look at literacy dollars, and literacy demographics

Thursday: Literacy initiative tests political patience, and political will

Thursday: As Idaho revamps its literacy program, its reading test awaits a rewrite

Thursday: Rethinking literacy for special education students

Thursday: No clear picture on funding for special education