Amber Patton saw her son’s kindergarten year slipping away.

Grady, her middle child, had little interest in learning to read. He had trouble paying attention, guessed on class assignments and wasn’t keeping pace with his classmates. The need for a child to catch up and read at grade level — something the politicians and education leaders often speak of, in somber but detached terms — was urgent and urgently personal to Patton.

The turnaround came this fall, and it came quickly. Grady showed up for first grade at West Ada’s Chaparral Elementary School unable to write his name. Now he has caught up from kindergarten. He is learning sight words and reading more quickly. And like his older sister, Emerson, an avid reader now in third grade, Grady is sneaking in reading after bedtime.

“I seriously never thought that would happen, and he’s doing it all by himself,” said Patton, a surgical scrub technician from Meridian. “It was a very exciting moment.”

Behind every score on the Idaho Reading Indicator, behind every intervention plan to help an at-risk student, there is a child’s story. And the parents’ story.

Stories of struggles, successes and uncertainties.

Introduction to phonograms: ‘I as a parent learned so much’

Before her son Krew showed up for first grade at Chaparral last year, Britteny Gardner had never heard of phonograms.

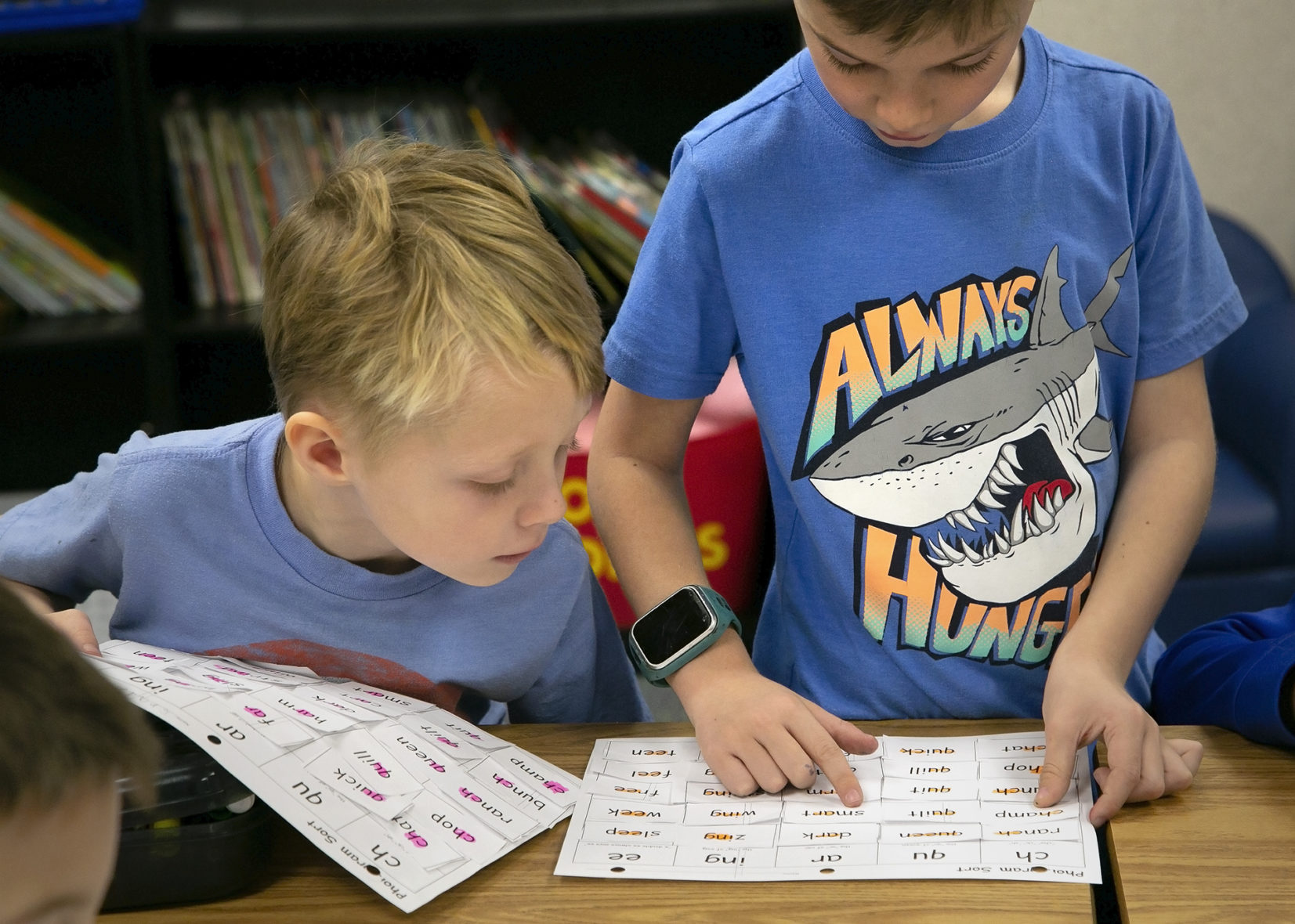

Chunks of letters within words — the “igh” in “light,” the “er” in “her” — phonograms are the building block of first-grade reading instruction at Chaparral. Reading exercises pop with the neon marks of highlighted phonograms. Teachers say their phonogram focus helps kids decipher words and grasp spelling.

The results: 83 percent of Chaparral’s first-graders were reading at grade level this spring, compared to 78 percent of first-graders districtwide and 67 percent of first-graders statewide.

Krew is now in second grade, and Gardner is hoping his background in phonograms will help him shore up his reading speed. She’s encouraged because she sees him use phonograms to break down longer words that slow down his reading.

Gardner is seeing other differences, as she helps her second child learn to read.

She would “partner read” with her first son, Ashton, now at Meridian High School. With Krew, she talks more about comprehension and context — partly on her own, partly at the urging of Krew’s teacher, who provides parents with a list of questions they should ask about reading assignments.

Recently, to her surprise, Krew accurately predicted that the book he was about to read would be non-fiction.

“You think about the difference between a superficial conversation and a real connection, and that’s really powerful,” she said.

‘We’re a very diverse community:’ Do parents have the resources they need?

When Emily Olson and her husband moved from Washington, D.C., to Boise, they put a lot of thought into selecting a school for their son Oliver.

They settled on Boise’s Whittier Elementary School, attracted by its English-Spanish dual immersion program.

But as Oliver begins kindergarten at Whittier, Olson has questions.

She’s happy that Oliver is reading confidently and picking up on phonics and decoding. But even though she sought out Whittier, she has mixed feelings. She wonders if his classmates have the resources they need to pick up their native language.

Whittier has some of the lowest reading scores in Boise — barely a fifth of kindergartners finished this spring at grade level — and district administrators trace the low scores to a compressed and divided school day of bilingual instruction. And in Olson’s view, it’s not a question of what the school provides. It’s a question of whether the kindergartners come in prepared.

A former math teacher who now works at the Lee Pesky Learning Center, a Boise nonprofit, Olson is taking off half a day a week to teach Oliver science. Her husband, an attorney, is taking off half a day a week to work on the social sciences. But at Whittier, where more than 98 percent of students live in poverty, most parents can’t rearrange their work schedule and fill in the learning gaps.

“I have a lot of wonders and concerns over that,” Olson said.

Nurturing a natural reader: ‘You just kind of encourage it when it happens’

Some children just take to reading.

Michael Lopez’s daughter Neah is one of those kids.

She was always interested in reading, except for a phase when she lost interest because a cousin told her reading was boring. “I think she got over that,” said Lopez, a web developer at the University of Idaho.

Lopez and Neah read together nightly, and lately Neah has taken to Mad Libs. The nonsense fill-in-the-blanks stories help her learn parts of speech.

Lopez isn’t sure where Neah’s future will take her. A year ago, as a kindergartner at Moscow’s West Park Elementary School, she said she wanted to grow up to be a kindergarten teacher. But now she’s a first-grader, and she isn’t talking as much about that. But Lopez thinks the state’s multimillion-dollar early literacy push is the right investment, for Neah and her classmates.

“No matter where they go, I think they’ll be better off if they read well,” he said. “It’s kind of a no-brainer.”

‘We’re the ones standing in the way:’ Engaging in education

Patton was concerned as Grady began first grade at Chaparral. His teacher, Katie Conway, allows kids to figure out where they want to sit, and Patton wasn’t sure how that would play out. But Grady found a seat, and a group of classmates, that made him feel comfortable.

Now, Patton raves about Conway — and her emphasis on small-group reading instruction. From an adult’s perspective, Patton said, it makes sense. Even grown-ups don’t always like to speak up in a large group.

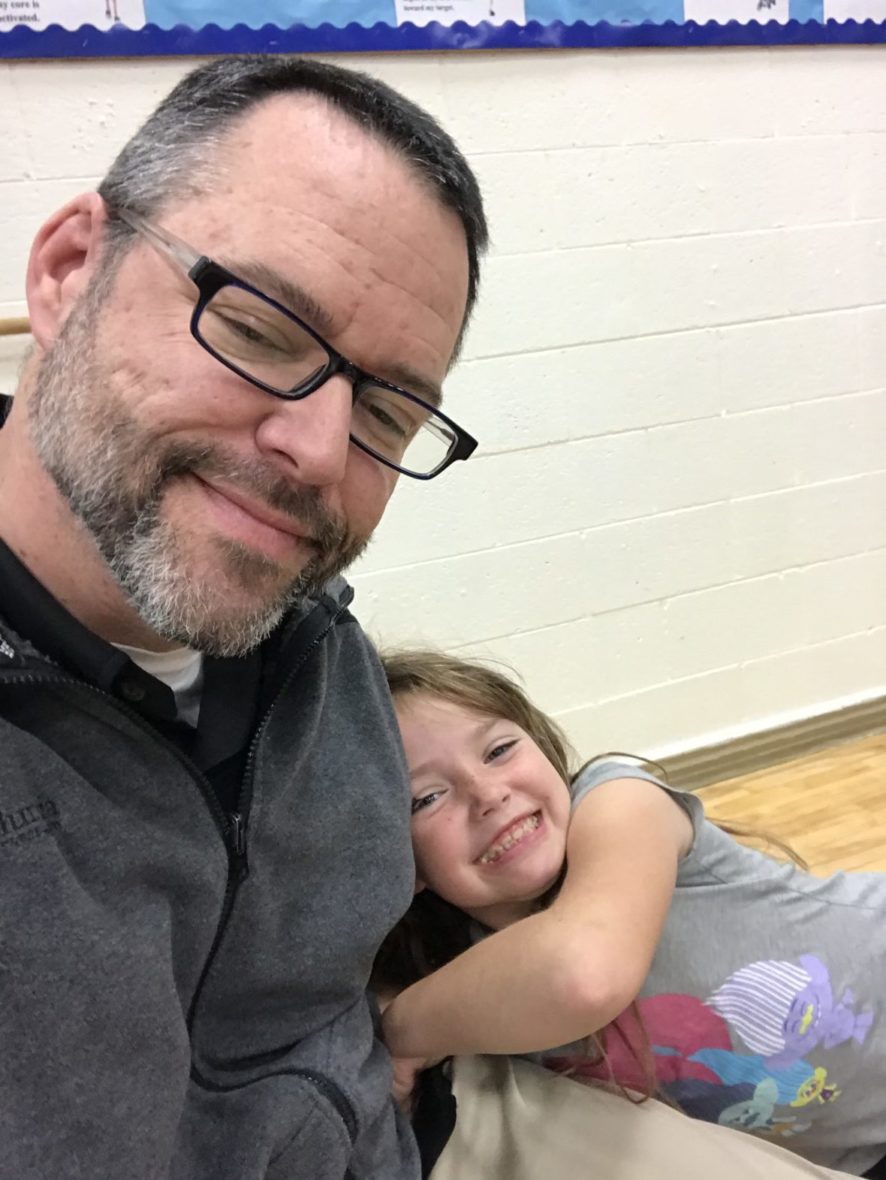

Patton has watched her son’s improvement, both at home and in school. She volunteers every other week in class, and has learned more about Grady’s education than she imagined she would.

Ask Patton about the obstacle — the one thing that keeps young children from learning to read — and she doesn’t blame the teachers or the politicians. She puts it on her fellow parents.

“We’re the ones standing in the way.”

Idaho’s reading challenge: This series at a glance

Day One

Reading realities: Idaho plays catchup

Following the dollars, defining success

Day Two

What’s working? School success stories

Idaho’s daunting demographic hurdles

Day Three

Testing kids, and seeking answers

Early education expands across Idaho

Day Four

Reading policy and reading politics

Parents tell their stories