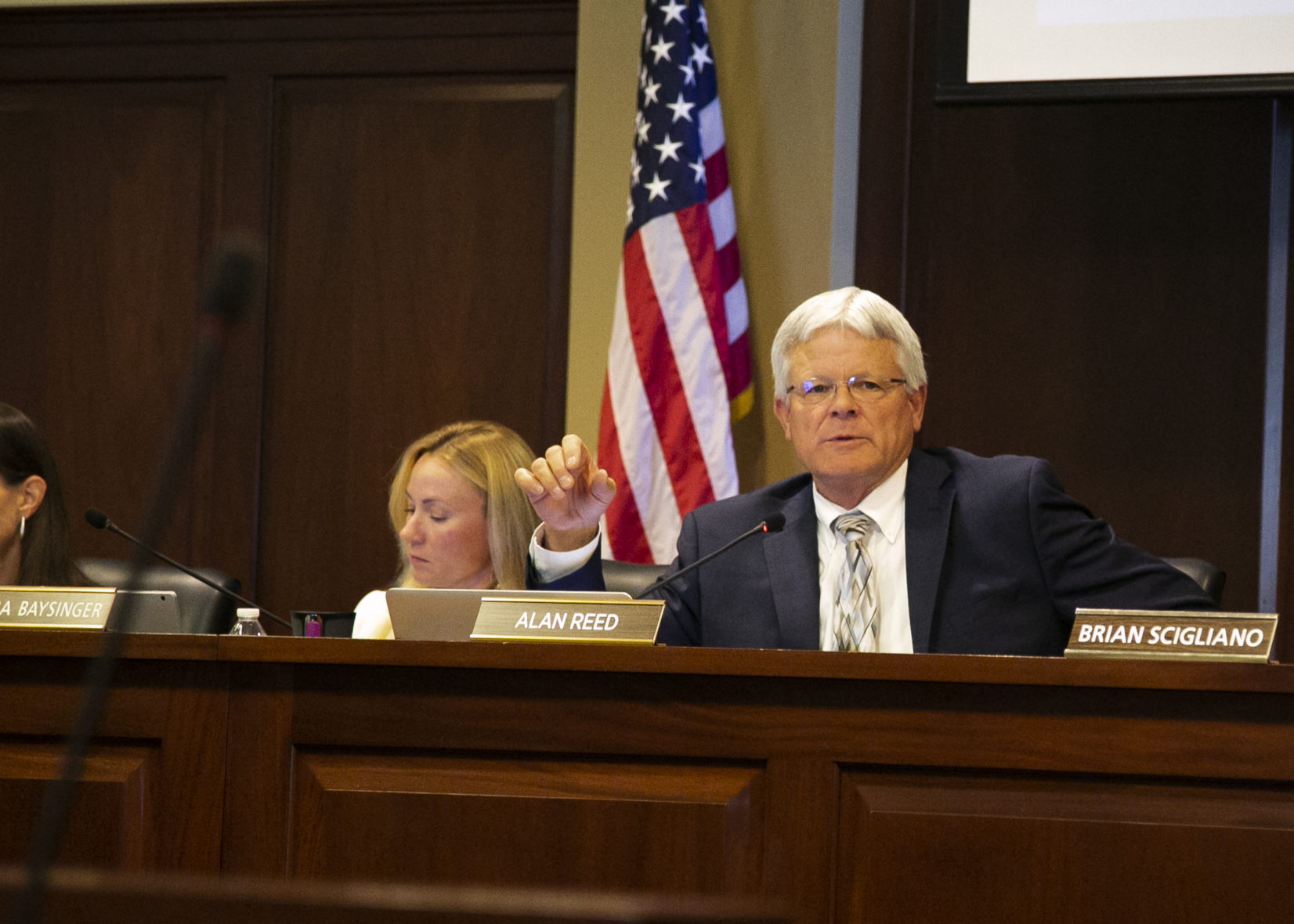

IDAHO FALLS — Alan Reed leads a successful dairy business and popular ice cream empire. But in his spare time, he chairs one of the most controversial committees in Idaho public education. The professional and public service roles can seem worlds apart, but Reed sees some parallels.

“You should deal with the FDA like I have to,” he recently recalled telling a local charter school leader bothered by his committee’s state oversight role.

Reed, a third-generation owner of Reeds Dairy, chairs the Idaho Public Charter School Commission, a panel that oversees 57 Idaho charters — nearly three-fourths of the state’s total of 75.

After reshaping the family dairy into a successful business decades ago, he dove into education leadership, serving for years as a trustee in the Idaho Falls School District before being appointed to the commission.

Today, Reed, who drives a black diesel pickup and wears Wranglers, has a say in approving or closing the taxpayer-funded schools.

It’s not always as simple as mixing cream with sugar, Reed acknowledged, and it can be much more political.

“It’s a hard balance,” he said.

From farmhand to business man

Reed’s family dairy lies on the outskirts of Idaho Falls, where his great grandfather bought land in 1930.

Reed recently breezed through some family history from his office on the same sweep of land. How his dad and two uncles went on to run the dairy, selling cream to another local ice cream company. How he worked on both the dairy and another nearby family farm growing up. How he was ready for a change by the time he finished high school.

Reed went off to Ricks College — now BYU-Idaho — in nearby Rexburg but didn’t finish. Instead, he returned to the dairy and worked up a business proposal for his dad and uncles.

Rather than selling the dairy’s cream to the Farr Candy and Ice Cream Company across town, the dairy should make its own ice cream, he said. “I saw a market for it pretty early on.”

The men bought into the idea and sent Reed back to school. He enrolled in North Carolina State University’s food science program in 1984.

But again, he didn’t graduate. Equipped with the information he thought he needed to create the best ice cream, he returned to East Idaho early and set out for the right mix of cream and sugar.

After six months of taste testing with family members and “throwing out a lot of ice cream,” Reeds Dairy ice cream was born.

The ‘other’ family profession

By 1985, Reeds Dairy was making its own ice cream, and morphing into a milking, bottling and sales company that would eventually send specialty dairy products across the country and oversees.

But another family profession — and an expectation — had crept into the Reed household.

Reed’s wife Holly began working at a local elementary school in 1979 and snagged her first teaching job in the Idaho Falls School District four years later. Her mother was also a local elementary school teacher.

Education was a part of the family, too, Holly Reed recently told Idaho EdNews.

Reed worked on the business full time, and would eventually became its president. But something else pulled on him, and education was a driving force.

It wasn’t an expectation, Reed said, recalling the various boards and committees his forebearers had been on, including his dad’s seat on the National Potato Committee. But some sort of public service role beckoned.

“I didn’t want to be like that,” Reed said of his father’s prior commitments, “but I did have a desire to serve.”

He ran successfully in 1994 for a seat on Idaho Falls’ school board. He recalled the flashpoint issue that election cycle: sex education.

“It’s funny how issues repeat themselves,” he said, referencing recent debate and contention over a House bill aimed at requiring parents to sign permission slips for youth to learn about human sexuality in Idaho’s schools.

From trustee to commissioner

Reed served as an Idaho Falls trustee until 2004, chairing the board for seven years.

Then the governor’s office called with a request. Would he serve on the state’s fledgling seven-member commission tasked with overseeing a growing number of public charter schools?

Reed admits not knowing much about charters at the time, but “you don’t get a call from the governor’s office everyday.”

“I took it as an honor,” he said.

Reed accepted, and leaned into his accounting and business experience to “work schools over on their budgets” and other potential financial issues the commission uncovered, he recalled.

Accountability is still a focal point for the commission. But the level to which that happens is a lingering source of debate when it comes to the commission’s charters, which seek renewal before the oversight body every five years.

That process revolves largely around assessing a school’s student achievement and operational track record, including issues of financial distress or possible misuse of public funds.

The commission can close charters that don’t meet standards, but it doesn’t happen. Since its inception in 2004, the oversight body has closed just one of its schools, though several have consistently failed to meet performance expectations and make ends meet financially.

Reed recalled his early emphasis on questioning schools about their finances, but said his focus changed when he became commission chair in 2012, and “got cornered” by concerned lobbyists and charter administrators who said some schools had grown to fear and resent the commission.

“I had no idea,” Reed recalled, adding that his outlook on the commission’s role shifted to one more cognizant of “helping schools improve,” not threatening to shutter them.

But in 2019, finding that balance between accountability and granting schools flexibility reached a boiling point, and found Reed reassessing even more his purpose on the commission.

‘You know I don’t like being recorded’

“You know I don’t like being recorded,” Reed joked during an interview for this story.

The intended comical reference stemmed from a not-so-comical event from the spring of 2019, which found Reed and his fellow commissioners reeling after audio from a closed-door meeting became public.

On April 11, 2019, commissioners and staff met for nearly two hours behind closed doors. The meeting’s stated purpose was legal, since commissioners needed to review confidential student data. But the discussion drifted and found the group talking about closing some struggling charters, and how to convince legislators to get on board.

The commission made critical remarks about Jerome-based Heritage Academy, its administrator and the community. At one point, Reed voiced regret that the school remained open. He later apologized and asked to meet with Heritage officials, who declined.

Attorney General Lawrence Wasden’s office concluded that the commission likely violated Idaho law during the meandering meeting. Commissioners later admitted to breaking the law and underwent open-meeting training from a Wasden deputy.

Critics, who had long viewed the commission as a problem, pounced. “The lights went on,” said Coalition of Idaho Charter School Families President Tom LeClaire, who told EdNews in 2019 that the meeting confirmed his suspicions about how the commission views some of its schools.

LeClaire’s group had emerged as an ally and voice for parents and students at some charters struggling academically and financially. For LeClaire, the meeting was the last straw.

“It’s become a dead relationship, and that’s not what we want,” he said amid the fallout.

Reed found himself again reconsidering the balance between accountability and flexibility.

“There is an issue, and rightly so, of trust,” he told EdNews in the summer of 2019.

‘A wonderful thing’

Reed recently recalled the ordeal with a smile from his uncle’s former home on the farm, which now serves as office space for the family business.

A receptionist’s desk rests just inside the front door. An old kitchen table is now a conference table in Reed’s office down the hall.

But the botched meeting — and its backlash — have further shaped his outlook on charters and the purposes they serve.

He pointed to two recent graduation ceremonies he attended: one featuring students at a high-performing charter and one for students at a low-performing virtual charter.

“Some of those kids wouldn’t have graduated had it not been for online schooling,” he said of the group of online learners. The school might struggle, he added, but helping kids achieve something they might not have is “a wonderful thing.”

Yet while LeClaire and others may chafe at efforts to scrutinize charters, other prominent leaders have raised questions about whether the commission does enough to hold some of its schools accountable to taxpayer investments — including its virtual schools, which continually struggle when it comes to student achievement.

“That is their job,” said outspoken charter advocate and Bluum CEO Terry Ryan, who has called for greater scrutiny of struggling charters. In 2019, Ryan compared student achievement at charters to the classic spaghetti western “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly” and suggested that schools that continually struggle, including virtual ones, should close.

That hasn’t happened under Reed’s watch, but other officials have expressed confidence in the commission’s approach. House Education Committee chair Rep. Lance Clow told EdNews Reed is a “dedicated,” leader, especially when it comes to charter schools.

Clow, who’s known Reed for six years, said his committee has always relied on Reed and the commission for “sincere and truthful” information. (Senate Education chair Steven Thayne told EdNews he had nothing to add for the story and doesn’t work much with Reed.)

From his office on the farm, Reed reiterated his goal to continue providing time for struggling schools to improve instead of shutting them down — an emphasis he’ll continue if he’s allowed to.

“Another call from the governor to keep going would be hard to turn down,” said Reed, who’s term on the commission expires next year.