(UPDATED, 4:42 p.m., to clarify mainstream groups’ endorsements in the state superintendent’s primary.)

Despite everything that happened in Tuesday’s primaries, nothing was settled.

Not when it comes to the pointed and public battle within Idaho’s Republican Party.

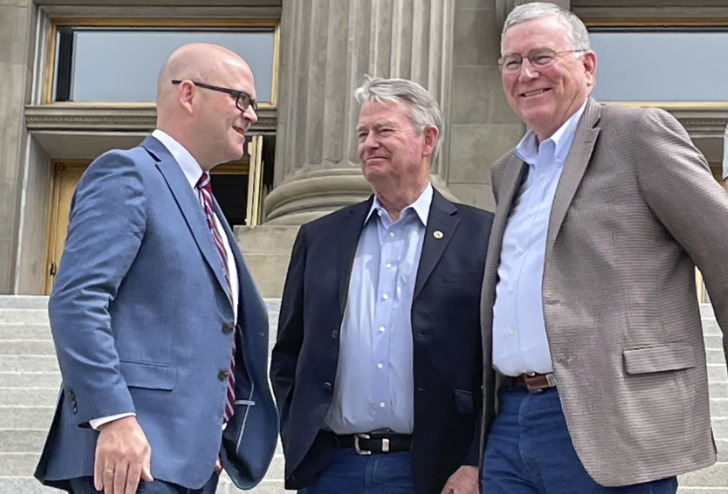

Mainstream Republican voters showed up big for incumbent Gov. Brad Little and his de facto running mate, House Speaker and lieutenant governor’s candidate Scott Bedke. But conservatives ousted 20-year incumbent Attorney General Lawrence Wasden with surprising ease. A stunning series of upsets unseated 20 sitting legislators — mainstream and hardline Republicans alike — as the Senate moved unmistakably to the right.

No overarching patterns. No clear winner in the civil war within the GOP.

And races that each took on their own personalities:

- Little ran a well-funded and clinical re-election campaign, building on the broad base of urban and rural support that carried him through a much more closely contested 2018 primary. He carried every county in the Mountain Time Zone, 40 counties in all. Lt. Gov. Janice McGeachin made a lot of noise by trying to override Little’s COVID-19 policies, and played up her endorsement from former President Trump. But her candidacy never seemed to catch fire with voters — who were, possibly, turned off by her dalliances with white nationalists and her inability to keep a small state office in the black.

- Like Little, state superintendent’s candidate Debbie Critchfield enjoyed a fundraising edge from the start of the campaign. Her campaign seemed a bit vanilla and shy on details, but she was able to get out on the airwaves — and tout an endorsement from a durable Idaho GOP brand, former Gov. Butch Otter. Like Little, and Bedke, Critchfield’s rural roots helped her roll through southern Idaho, including counties that had come up big for Sherri Ybarra in the 2014 and 2018 primaries. Once Critchfield sealed up her base, and hardline conservative Branden Durst locked up his conservative base, Ybarra was an incumbent with no path to victory. She finished third, carrying only her home Elmore County.

- Ada County Clerk Phil McGrane did win the secretary of state’s primary, ugly. Here’s all you need to know: 57% of Republican voters were willing to vote for a chief elections officer who questioned the result of the 2020 presidential election. Trump’s endorsement might not have done McGeachin much good. But embracing Trump’s unfounded election narrative didn’t seem to hurt McGrane’s opponents, Rep. Dorothy Moon and Sen. Mary Souza.

- Former U.S. Rep. Raul Labrador didn’t just unseat the incumbent Wasden. His primary win was about as resounding as Little’s. Labrador carried 37 of 44 counties. In Kootenai County, Idaho’s emerging far-right epicenter, Labrador racked up a 70% majority over Wasden and Coeur d’Alene attorney Art Macomber. Provided he wins in the general election, Labrador is the face of Idaho’s far right — assuming he wants the role.

Some geographic trends emerged.

Ada County came out strong for mainstream statewide candidates. McGrane piled up an 18,000-vote advantage in his home county — and since he defeated Moon by only 4,200 votes statewide, he needed the boost. (Yet, even in Ada County, conservatives made gains; in a hotly contested Boise state Senate race, Rep. Codi Galloway unseated Sen. Fred Martin.)

To a lesser degree, the Magic Valley and Eastern Idaho went mainstream. And that might have contributed to a few of Tuesday’s legislative upsets, as Eastern Idaho voters turned out hardline conservative Reps. Ron Nate of Rexburg, Karey Hanks of St. Anthony and Chad Christensen of Ammon.

And if anything, the Panhandle might have shifted even further to the right. It’s where the hardline statewide candidates put up their best numbers — and where voters booted out several moderate legislators, such as Sens. Jim Woodward of Sagle and Carl Crabtree of Grangeville and Rep. Paul Amador of Coeur d’Alene.

Yet despite these mixed results, and despite the complicated geography, McGeachin and Durst both tried to ascribe their losses to a conspiracy: a massive crossover vote.

“Brad Little barely managed a majority even with tens of thousands of Democrats and liberals infiltrating the Republican primary to support him,” McGeachin wrote on her Facebook page, without evidence.

“The @IdahoGOP must address its Democrat primary crossover problem,” tweeted Durst, a former Democratic legislator. “At least 20K liberals disrupted the primary and many establishment candidates encouraged them.”

To be sure, Take Back Idaho — and one of its leaders, longtime Idaho Republican Jim Jones — urged independents to vote in Tuesday’s primary. But in an Idaho Statesman interview Wednesday, the secretary of state’s office — run by a Republican, Lawerence Denney — denied the McGeachin-Durst claims of widespread crossover voting.

The crossover conspiracy narrative raises a basic question about voter enfranchisement: who is sufficiently Republican to participate in a Republican primary? And it gets at something else: Who drives Republican Party policy in perhaps the nation’s most Republican state?

Simply put: Who’s in charge here?

Tuesday’s primary didn’t answer that question, because both factions of the GOP shared a piece of the prize.

The mainstreamers got the wins they had to have. They nominated Little, Bedke and McGrane. Mainstream groups were clear in their disdain for Durst (one, the Idaho 97, endorsed Critchfield, while Take Back Idaho remained neutral). They also took out some legislative hardliners.

The right wingers got wins they had to have. Labrador gave them a statewide win, and a chance to take out an incumbent who had rankled more than a few conservatives. The right wingers also picked up a beachhead in the Statehouse: They now have a conservative cadre in the Senate, which could breathe new life into hot-button legislation that House hardliners have pushed for years.

The intraparty power struggle continues, into the next GOP primary, and likely beyond.

Kevin Richert writes a weekly analysis on education policy and education politics. He is writing two followups this week on the 2022 primary election. On Wednesday, Richert took a closer look the tumultuous legislative primaries.