MARSING – A line of adults stood outside of the Marsing School District building on a recent Wednesday, waiting their turn to get into a community food pantry. Across the lawn, 4-year-olds rode tricycles around a preschool playground, bundled up against the winter cold.

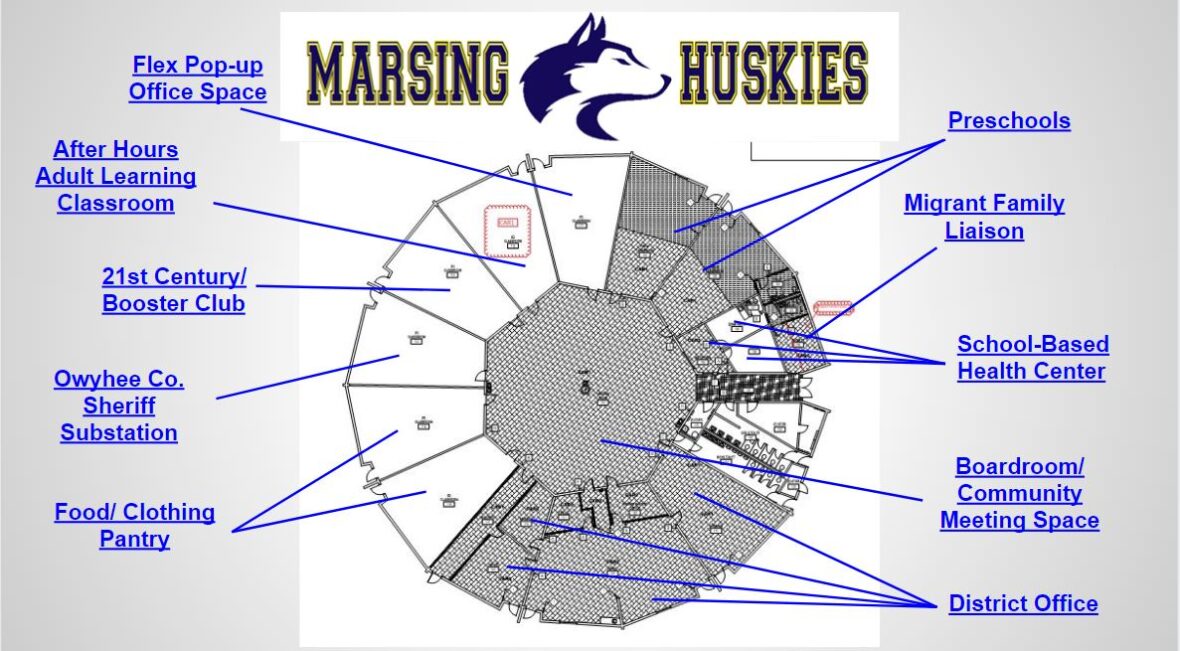

This is the HUB, a community school opened by the Marsing School District nearly two years ago, at the site of its former middle school. The aptly-named, wheel-shaped building is a one-stop shop for family resources that are scarce in the rural community. The school houses the only food pantry in town, after school programing, preschool, and student mental health services.

Community schools operate as a collaboration between school districts and local agencies, to provide families with all kinds of supports and resources they might need outside of the classroom. The model, popular across the country and in the Treasure Valley’s urban districts, is gaining traction in smaller and more rural districts across the southern part of the state. Groups like United Way of Treasure Valley and the Idaho Blue Cross Foundation are working to help the model catch on statewide.

“The concept could be done really anywhere,” Marsing superintendent Norm Stewart said. “It’s amazing how once you start things rolling, people are more than happy to come in and provide help to your families, which in turn — which is key — helps our kids.”

Foundations aim to align schools, healthcare and the community

United Way of Treasure Valley helped introduce the Community Schools strategy to Idaho, after a 2014 community needs assessment found that while the Boise and Ada county areas had plenty of resources for struggling families, the families didn’t have many connection points to access those resources, said United Way collaboration manager Hayley Regan.

Bringing those resources directly to schools was one strategy to help.

The Boise School District was the first to open community schools in Idaho in 2016. By 2020, at least 30 community schools were in operation across the southern part of the state, according to the Idaho Coalition for Community Schools.

A 2017 report by the Learning Policy Institute, where researchers reviewed 143 studies on community schools, determined that when implemented well the model can improve student and school outcomes, and help meet the needs of students in high-poverty schools.

Community schools look different in every district, but they share four core principals:

- Providing integrated supports: food pantries, clothing closets, health services and mental health services to meet student and community needs.

- Extended learning opportunities: before and after school programs, summer programs, community classes, etc.

- Family and community engagement

- Collaborative leadership practices

To build a community school that really addresses the needs of the community, districts have to engage parents and community partners and students in making decisions about what the school should look like.

“It’s about kind of undoing the traditional idea that only the leaders in education — superintendents and principals — can make decisions for their school,” Regan said.

United Way helps foster a collaborative of Idaho educators doing community school work, called the Idaho Coalition for Community Schools, and provides direct funding for a handful of the schools, like Marsing, where it pays the salary of community schools coordinator Becky Barkell.

Next year, United Way, the Blue Cross of Idaho Foundation and outside funders are planning to launch two cohorts of community schools that will receive specialized training and support for building or sustaining these community hubs.

Jackie Yarborough, senior program officer at the Blue Cross Foundation, hopes to see the model spread across the state.

“It’s about connecting the right leaders and the right systems,” Yarborough said. “When you can align school, healthcare and the community, that can be very powerful.”

“It’s pretty much a godsend”

Barkell, Marsing’s community school coordinator, started as a paraprofessional in the district eight years ago, but she’s been in Marsing for much longer than that. She knows the communities’ needs, because they’ve been her needs, too.

Barkell moved to Marsing 17 years ago, after a career in human resources in Nampa and Meridian. She had a young child, and with no preschool option in Marsing, Barkell stopped working to stay at home with her kids. At one point, Barkell’s husband lost his job, and when her family needed supplies from a food pantry, she had to drive the 15 miles into Caldwell or Nampa for supplies.

The new community school breaks down those barriers: It offers free preschool for Marsing kids, a clothing closet, adult education classes, after school programs, and student mental health services. The Hub has a part-time nurse on site a few days a week and Barkell arranged a free vision clinic last year where more than 100 people got free eye exams and glasses.

“This is wonderful, because we’ve been able to bring Marsing several resources they’ve never had before,” Barkell said.

On Wednesdays she opens the food pantry — the only local place Marsing residents can pick up free food supplies after a church-run pantry closed down.

As community members take what they need from the shelves, Barkell restocks behind them to make sure the next family gets what they need. In early November, Barkell served more than 90 families in a single day.

“They help more people than they think,” said one shopper, a 64-year-old man who asked that his name not be used. He lives on disability and had medical expenses recently. Without the pantry, he said, he doesn’t know how he’d survive the winter. “It’s pretty much a godsend,” he said.

Vicky, a Marsing parent, grabbed blocks of cheese and snack bars as she circled the pantry last week.

“It helps a lot to get some extra help with the kids. They go through a lot of food, and food prices have been going up big time,” she said.

Vicky says she doesn’t feel judged at Barkell’s pantry. On other visits, waiting her turn in line, she’s heard folks start to talk about what they could give back to the space — on this visit, Barkell has a box of peppers grown by a local senior citizen. Barkell will take him a box from the pantry on occasion, and sit with him in the summer time, watching the traffic from his porch.

“It’s nice to see the bond that the community is getting,” Vicky said.

The wheel-shaped “Hub” has individual spaces for its separate programs. An adult learning classroom is the site of classes on parenting and English as a Second Language.

One room is a substation for the Owyhee County Sheriff’s department. Stewart says it offers the school a sense of security to have police vehicles in the parking lot, and deputies only steps from the school building.

Three preschools operate from the building. The local Head Start program teaches low-income students who qualify for that program. The Canyon-Owyhee School Service Agency, which contracts with districts for special education services, provides a developmental preschool on-site. And Marsing launched a free preschool program, called Husky Pups, when it opened the HUB two years ago.

Students can also visit an on-site mental health counselor at the HUB during their regular school hours, and the district has seen so much demand for those services it’s looking for a third counselor to join the team.

Where some schools might focus on referring families out to nearby services, Stewarts’ vision for the HUB is to bring services directly into the school, which families might otherwise struggle to access in the rural community.

“If we could provide something that would address our students’ needs, which are really our families’ needs, that would help us with being able to educate kids,” he said.