BURLEY — On a recent afternoon, students streamed in to see their school counselor. Whether they were left out at recess, gossiped about, punched by a peer, hungry after missing breakfast, or experiencing anxiety and stress, they each turned to Aimee Hurst for help.

It was just a typical afternoon for Hurst, who serves the more than 500 students at Mountain View Elementary.

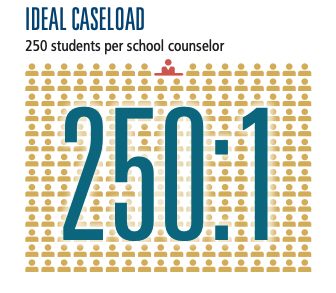

That ratio of 500 students to one school counselor is double the 250-to-1 ratio recommended by the American School Counselor Association. And Hurst’s situation isn’t unique — statewide, Idaho has an average ratio of 400-to-1.

Nationwide, statistics are very similar, with an average ratio of 480-to-1 for the 2021-2022 school year. Last school year, only two states reported averages within the ASCA recommendation.

The national organization advocates for reduced ratios because of the benefits to students. Having more counselors on staff often leads to:

- Increased standardized test performance

- Increased attendance

- Increased GPA

- Increased graduation rates

- Decreased behavior issues/disciplinary infractions

- More conversations with counselors about college and postsecondary plans

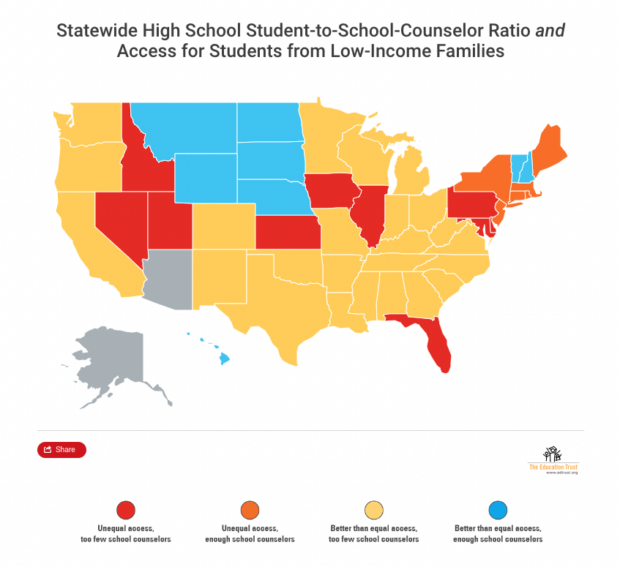

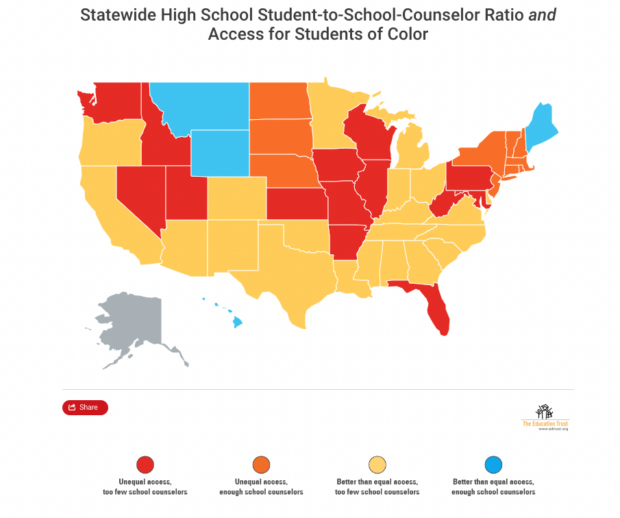

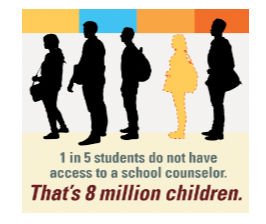

And the ASCA has found that “many students lack sufficient access to school counselors,” especially students of color and students from low-income families.

Making the issue even more pressing is the increasing need for mental healthcare among American adolescents.

But realistically, there’s not enough available funding to hire more counselors, according to Hurst, who is also the president of the Idaho School Counselor Association.

“If a school has to choose between hiring a teacher and hiring a school counselor, they’re going to hire a teacher,” Hurst said.

What school leaders can do is be thoughtful about the duties assigned to the counselor so they can primarily focus on helping students directly.

This week, Feb. 6-10, is National School Counseling Week.

A school counselor’s role can quickly become overwhelming

School counselors primarily act in crisis prevention — they work to get distressed kids calmed down and back in class. For extended or long-term mental health services, students need to see clinicians outside of school. In some schools, partnerships have brought those healthcare providers into school buildings to improve access for kids.

And while clinicians in schools help kids, they often don’t alleviate pressure from school counselors, who have a very different role.

Some districts hire College and Career Ready advisors, but there are just 42 such full-time positions throughout the state, so not all counselors have that assistance. Plus, many counseling duties required specific qualifications, such as a master’s degree in school counseling.

In addition to crisis prevention and helping the students who file into their offices everyday, school counselors might have a range of duties, depending on the school, which could include:

- Serving in leadership positions and on various committees

- Overseeing testing

- Overseeing Individualized Education Plans and 504s

- Occasionally covering classes for teachers

- Teaching classes on issues like bullying, healthy coping mechanisms, etc.

Historically, the roles of a school counselor haven’t been well-defined, and that’s led to plates filled with extra duties. The ASCA has worked to combat that by outlining appropriate and inappropriate duties, but oftentimes, schools are short-staffed and have few options.

Hurst, for example, has taken on some school nurse duties — like teaching programs about child abuse prevention, vaping prevention, and maturation.

Supporting school counselors when funding is limited: reassign duties, offer thanks, and seek community partnerships

Hurst suggested schools seek counseling interns to help lighten loads, or assign duties like test administration to paraprofessionals.

Amy Johannesen, a counselor at Lewiston’s Centennial Elementary School and ASCA’s Idaho school counselor of the year, said expressing appreciation for school counselors goes a long way as well.

“Taking the time to share how what the counselor is doing is making a positive impact with the students (matters because) if we don’t communicate that with people then they don’t know and they don’t realize.”

Johannesen serves nearly 400 students, which is an improvement from a few years ago when the district’s five elementary school counselors served seven primary schools. Now, there’s a counselor at each school.

Still, her days are busy.

“Our responsibility is to support the social-emotional needs, the academic achievement, and the college and career readiness for all of the kids in our building,” she said. “There’s not enough of me to meet all the needs, so just having another person would be huge.”

Other schools, like West Minico Middle School, have turned to innovative approaches — like working with community partners — to help meet student needs.

Brittany Rigby, a counselor at the school, told EdNews in January that she sometimes feels overwhelmed with more than 500 students to help.

“There are days when it feels like it’s impossible to meet the needs of all the kids because there’s just not enough hours in the day,” she said.

EdNews Data Analyst Randy Schrader contributed to this report.