DAYTON — About a dozen grade schoolers stood shoulder-to-shoulder near the cafeteria at the West Side School District’s Harold B. Lee Elementary School.

They laughed, wiggled and bumped into each other while waiting for lunch. Their principal, Melinda Royer, talked to students a few feet away.

No masks. No prodding the children to separate.

Physical distancing, mask mandates and remote learning have become focal points in Idaho and across the nation this back-to-school season. But leaders at West Side, a rural Southeast Idaho district surrounded by a sea of farmland and backcountry, emphasize different priorities amid the coronavirus pandemic.

“We want the kids to feel normal coming back,” said Superintendent Spencer Barzee.

Some safety precautions — “slight modifications,” as Barzee has called them — are in place at West Side:

- Staffers take students’ temperatures at the start of each school day.

- Heavily touched surfaces, including door handles and drinking fountains, are disinfected throughout the day.

- Students eat lunch in either the cafeteria or classrooms to promote some physical distancing.

Masks are optional, but just a handful of students and adults at the district’s three schools wear them. Likewise, only a handful of families participate in the district’s remote-learning option, Barzee told EdNews.

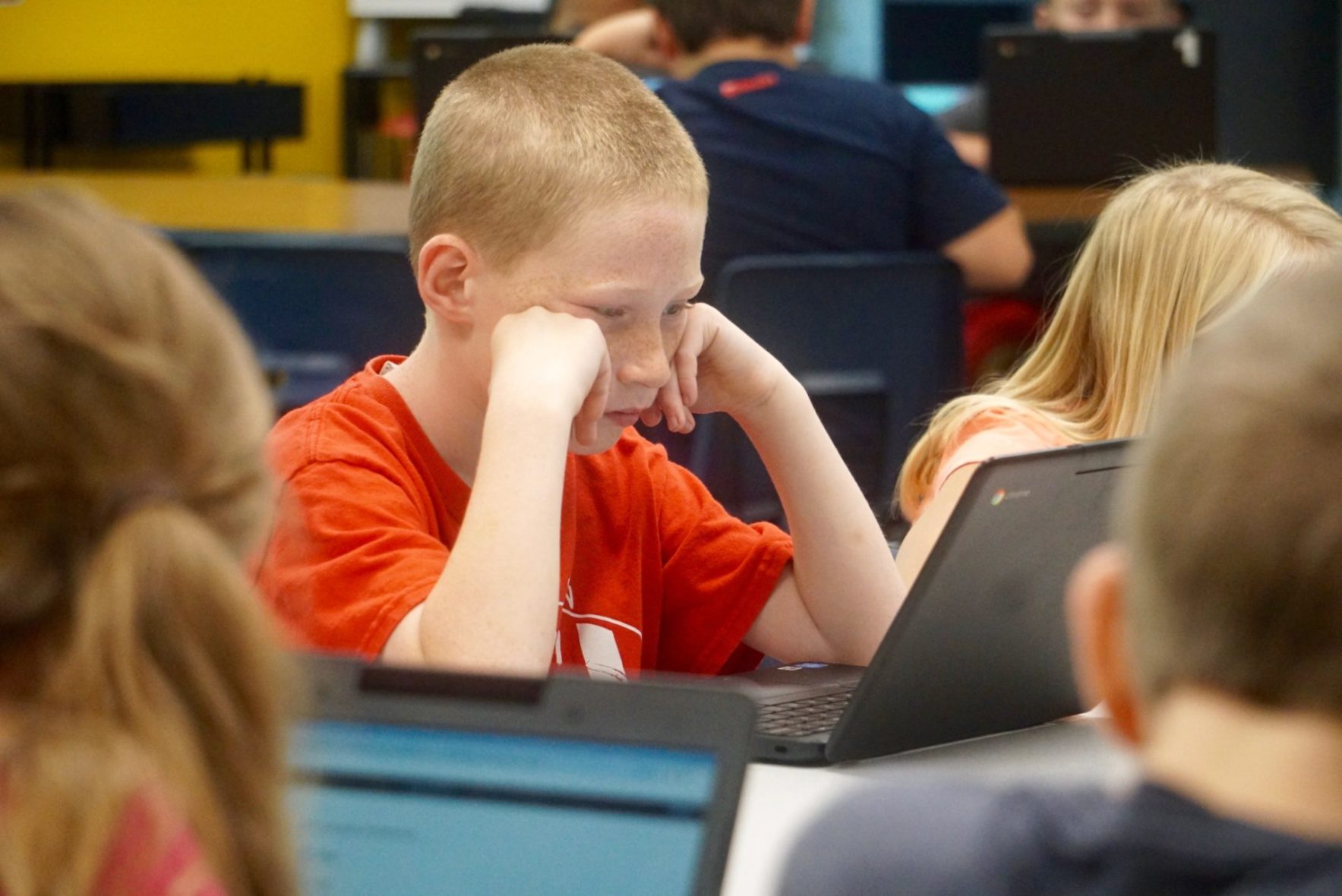

And West Side students don’t have to physically distance while in class. One elementary teacher outlined her classroom procedures with students in a circle on the floor Tuesday. Down the hall, students gathered at small tables to take reading-placement tests.

West Side places less of an emphasis on safety precautions than other Idaho districts, but it has its reasons. On top of the “need for some normalcy” in schools, Barzee pointed to variations in cases of COVID-19 across Idaho.

State numbers show 54 confirmed and probable cases in Franklin County, where the district is situated. By contrast, Idaho’s most populated Ada County is approaching 11,000 confirmed and probable cases. The West Ada School District opted Tuesday to join other Treasure Valley districts in starting the school year fully online.

Population plays an obvious role in the disparity. Ada County is approaching 500,000 residents, U.S. Census Bureau data show. Franklin County has fewer than 14,000.

Still, the case numbers have helped shape vastly different safety guidelines for Idaho’s schools. Central District Health recommends Ada County schools open in a “red” category, which calls for remote learning and closure of school buildings. Southeastern Idaho Public Health has put West Side — and all schools in the seven counties the department oversees — in a green, or “minimal” risk, category.

That designation lets schools reopen fully in person, with “physical distancing and sanitation” protocols.

Some Southeastern Idaho schools have implemented additional safety guidelines on their own. The Blackfoot district recently delayed an in-person start to the school year by two weeks, and students and teachers in the Pocatello-Chubbuck district must wear masks.

Barzee acknowledged that the outlook and safety guidelines in his district could change. It has in at least one other rural district. One week after its in-person reopening, central Idaho’s Mackay School District took instruction fully online after two staffers and a student tested positive for COVID-19. Some 70 Mackay students and three teachers are now in quarantine.

Yet for Barzee, the number of confirmed cases says only so much. “We also have to ask how many people are in the hospital, and how many people have died.”

As of Thursday, Franklin County had three active cases, one hospitalization and no deaths, according to Southeast Idaho Public Health.

Those numbers suggest that the district would harm students more by keeping them home or mandating “distracting” face masks than by bringing them back to school, Barzee said.

“Online learning as the primary method is not what is best for our students,” he told parents in July.

That message has resonated locally. A recent survey of 264 West Side parents revealed just 17 respondents — roughly 6 percent — feel “extremely uncomfortable” with a full return to school. Yet 162 — nearly 80 percent of respondents — feel “extremely” or “somewhat comfortable” sending their kids back in person.

EdNews spoke with at least a dozen West Side parents during a recent visit to the district. All of them expressed support for in-person learning with fewer health guidelines.

“Life must go on,” said Talina Roberts, who has a second-grader in the district. “Trying to teach all these kids at home last spring was a mess. Of course, things could change.”