Supplemental Levy Series

A new law requires transparent levy elections — but the results are mixed

Some districts write sketchy ballot language, which means voters can’t tell where their money is going. These districts are taking a big risk. The law would allow a judge to nullify an election over flimsy ballot language.

Districts lean on short-term levies to pay for long-term investments — people

School districts use the bulk of voter-approved supplemental levies to cover their single biggest expense: salaries and benefits. That allows schools to hire more teachers and reduce class sizes, or keep experienced educators in the classroom — as long as voters say yes to the levy.

All politics is local, and levy elections can be contentious or routine

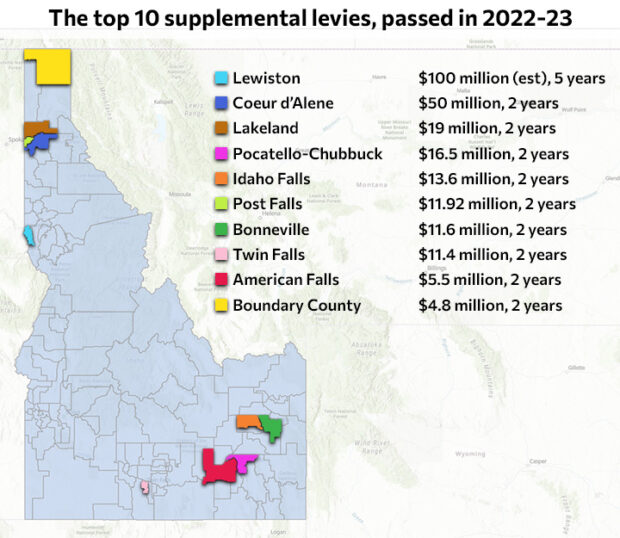

It took five months, and two loud elections, for Coeur d’Alene to convince their patrons to keep a supplemental levy on the books. But in many other communities, voters quietly and reliably support levies.

Lawmakers rewrote the school election calendar. What happens next?

Starting next year, school districts have only three dates when they can run a levy. But the schools also will have more state money — designed to offset bonds and levies. It’s a classic tradeoff, and a hard one to handicap.