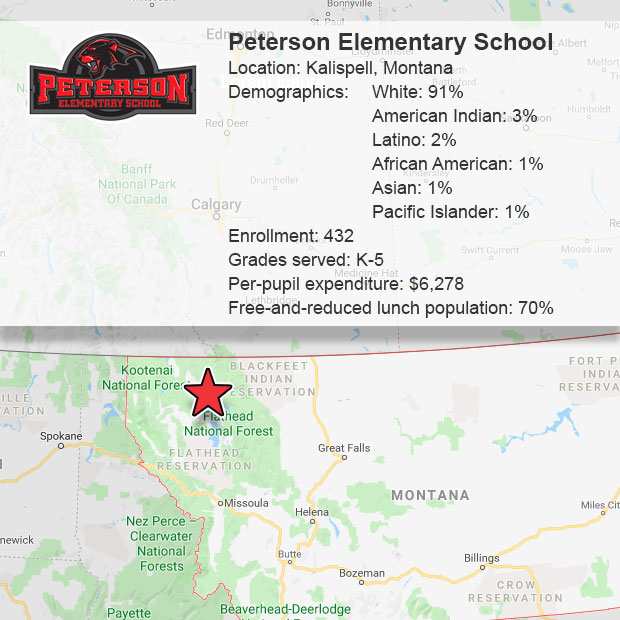

This is one of four stories featuring what some of the nation’s top-performing high-poverty schools are doing to boost achievement among students in poverty.

KALISPELL, Mont. — Teachers at Peterson Elementary School say it takes a “village” of educators to improve learning outcomes for students in poverty.

A village with a heavy emphasis on literacy.

Since 2013, educators at the high-poverty northern Montana school have employed a schoolwide program aimed at improving student performance in reading and writing.

The emphasis has raised more than just literacy rates. Even though about 70 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price meals, Peterson outperforms its Montana peers in both English language arts and in math — in most cases, by double-digit margins on standardized tests.

Yet Peterson teachers say the recipe for success requires more than a heavy focus on improving reading and writing. High-poverty schools need teachers who are “team players” willing to uphold high learning standards and avoid dwelling on poverty’s potential impacts.

“We almost forget that so many of our kids are even in poverty,” said Peterson principal Tracy Ketchum.

What Peterson does differently

Peterson teachers use testing data to place students into one of three literacy categories: advanced, on-level or below-level.

Grouping allows students to work on reading and writing assignments with learners of similar abilities from across a given grade level.

Advanced and on-level students each work daily with a grade-level teacher in groups of 20 to 25 students. Below-level learners work daily with a grade-level teacher in smaller “subgroups” of four or five students.

In addition to smaller groups, below-level learners in each grade have access to on-site reading and writing tutors.

Though each teacher oversees one of the three groups in their grade level, the teaching process is fluid, with educators often moving between classrooms and helping where they’re most needed during reading and writing time.

An “action” team, including a teacher-leader from each grade level, meets regularly with independent reading and writing consultant Neilia Solberg, who contracts with the school district. Solberg helps the group identify and implement best practices for improving instruction and literacy throughout the school.

Solberg and the action team also help ensure that teachers maintain high learning standards and align literacy curriculum both horizontally (among teachers in the same grade) and vertically (among teachers in varying grades).

How Peterson defies the odds

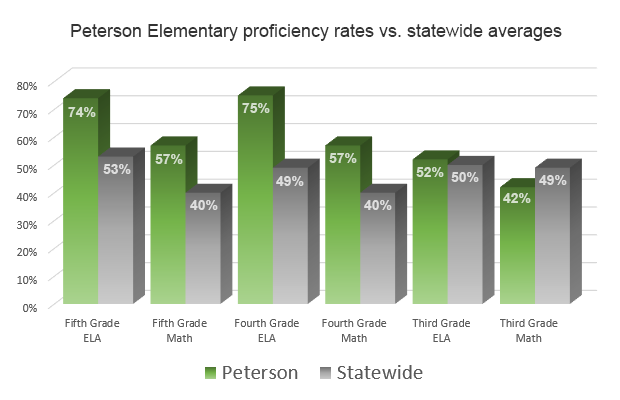

Despite its status as a high-poverty school, Peterson’s 2018 standardized test scores exceeded statewide averages in all but one academic achievement indicator: third-grade math.

In Montana, grade-schoolers start taking standardized tests in third grade. Here’s a comparison of proficiency rates between third-, fourth- and fifth-graders at Peterson and their statewide peers:

What works

Peterson teachers attribute the school’s high ELA and math scores to the heavy emphasis on improving literacy, because reading and writing skills are fundamental for success in all subjects.

“Improving literacy has definitely trickled into other learning areas here,” said third-grade action team member Kim Lister.

The school’s literacy program, bolstered by Solberg’s consulting, also helps close achievement gaps between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged students by providing extra resources to kids who need it most:

-

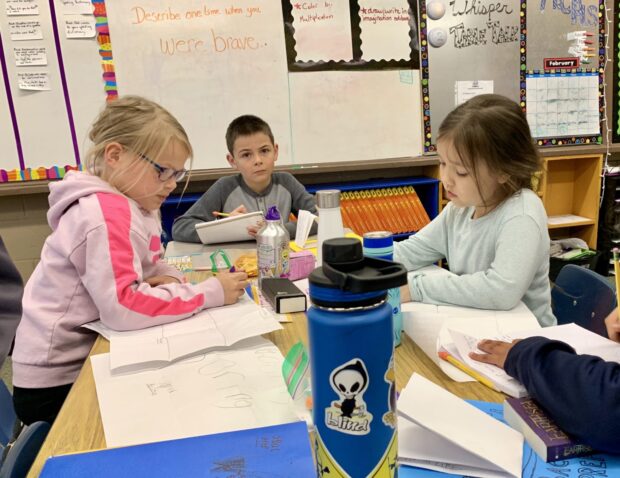

Peterson Elementary School students create storyboards in a small group. Smaller subgroups are aimed at facilitating group learning opportunities for below-level students.

- Tutors are in class to help struggling learners.

Identifying weak spots in order to provide appropriate interventions is crucial to help all students — especially those impacted by poverty, Lister said.

“Students in the learning gap need to hear things multiple times, so we keep spiraling back for them to help move that dial,” Lister said.

Smaller learning groups, tutors and teachers who help where they’re most needed combine to provide a “good support network to get struggling learners the resources they need,” said third-grade teacher Laurel King.

Sometimes needed resources extend beyond the classroom to include food and clothing for kids in poverty, King added.

“Nothing we do matters if kids go hungry,” Lister said.

But while Peterson teachers are sensitive to the poverty-related needs of their students, they also avoid allowing the issue to become a “crutch” for kids.

“We don’t let what’s happening to them outside of school affect what happens inside,” said Lister. “That’s a hard thing to do, but we can do hard things.”

The challenges

An intensive focus on literacy and remediation can distract from pushing the school’s gifted students to achieve more, King said.

“I’ve at times felt like my top performers might be getting a little neglected,” she added.

Ketchum said the time and resources needed to sustain the schoolwide literacy framework can be exhaustive — both for the school and for teachers.

“We have a lot of young teachers with young families, and we need to remember that,” Ketchum said.

Ketchum pointed to the literacy action team, which requires the school to find five substitute teachers every time the group meets.