When Gov. Brad Little talks to educators — or visits with his staffers’ kids or his own grandchildren — his passion for reading is renewed.

He’s convinced, again and again, that Idaho’s children need to learn to read by third grade, so they are prepared for learning and life.

“I have no reason to take my foot off the gas in that effort,” Little said in a recent interview.

In his first year as governor, Little pushed legislators to double Idaho’s literacy budget to $26 million. Legislators signed off, in a spending leap of faith that isn’t usually seen in the Statehouse.

Now, Little wants to send the message, to educators and legislators alike, that he’s in it for the long haul. He has the support of many educators, who say reading is the right priority.

But in the short run, the 2020 legislative session could be challenging. Money is tight and some lawmakers want to see results from what they spent a year ago.

Setting priorities, making tradeoffs

Every decision carries an opportunity cost. If an elementary school tries to pack more reading into a kindergartner’s day, there’s less time for math, art or money.

The same rule applies to public policy. If you put tax dollars into one project, you can’t use that money elsewhere.

By making literacy his top K-12 priority, Little is making tradeoffs. Kindergarten through third-grade scores on the Idaho Reading Indicator are lackluster, but the same could be said about Idaho’s high school math scores.

“I would like to see an equal emphasis on reading and math,” said Christine Ivie, administrator at Heritage Academy, a Jerome charter school.

Little is convinced he has set the right priority, for this year and for the years to follow. He explains it as do educators — including numerous teachers and administrators interviewed for this series. Reading is the building block for everything that comes after a student’s first few years of school. Little wants kids ready for classes in the “STEM” disciplines of science, technology, engineering and math. He wants high school students to be college- and career-ready, another chronic problem facing Idaho education. None of this happens if kids can’t read.

It’s the right long-term goal, state superintendent Sherri Ybarra said. “We’re not going to throw this out, because it’s good for kids.”

Emily Olson came around — but it took some convincing.

“The math teacher in me screams, ‘What about early numeracy?’” said Olson, the mother of a Boise kindergartner, who now works for the Lee Pesky Learning Center, a nonprofit that focuses on learning disabilities.

Ultimately, she agrees. As a learning pathway, reading wins out. And she admires Little’s willingness to champion this cause.

“It was time for it to be deeply meaningful to someone in that position,” she said.

But Little can’t make this happen without legislative support. Which brings us to 2020.

What will Little’s next literacy budget look like?

The first big question: How much will Little want to spend on literacy next year?

He’ll give his answer on Jan. 6, on the first day of the 2020 legislative session, when he releases his budget proposal.

Little telegraphed his intentions at the Associated Taxpayers of Idaho’s Dec. 4 conference. Speaking to 500 people, including a throng of legislators, Little said, “You are guaranteed to see me push for significant investments in our teachers and literacy efforts.” More broadly, Little has demonstrated his commitment to boosting K-12 spending, since he spared public schools from the midyear budget cuts he has imposed across state government.

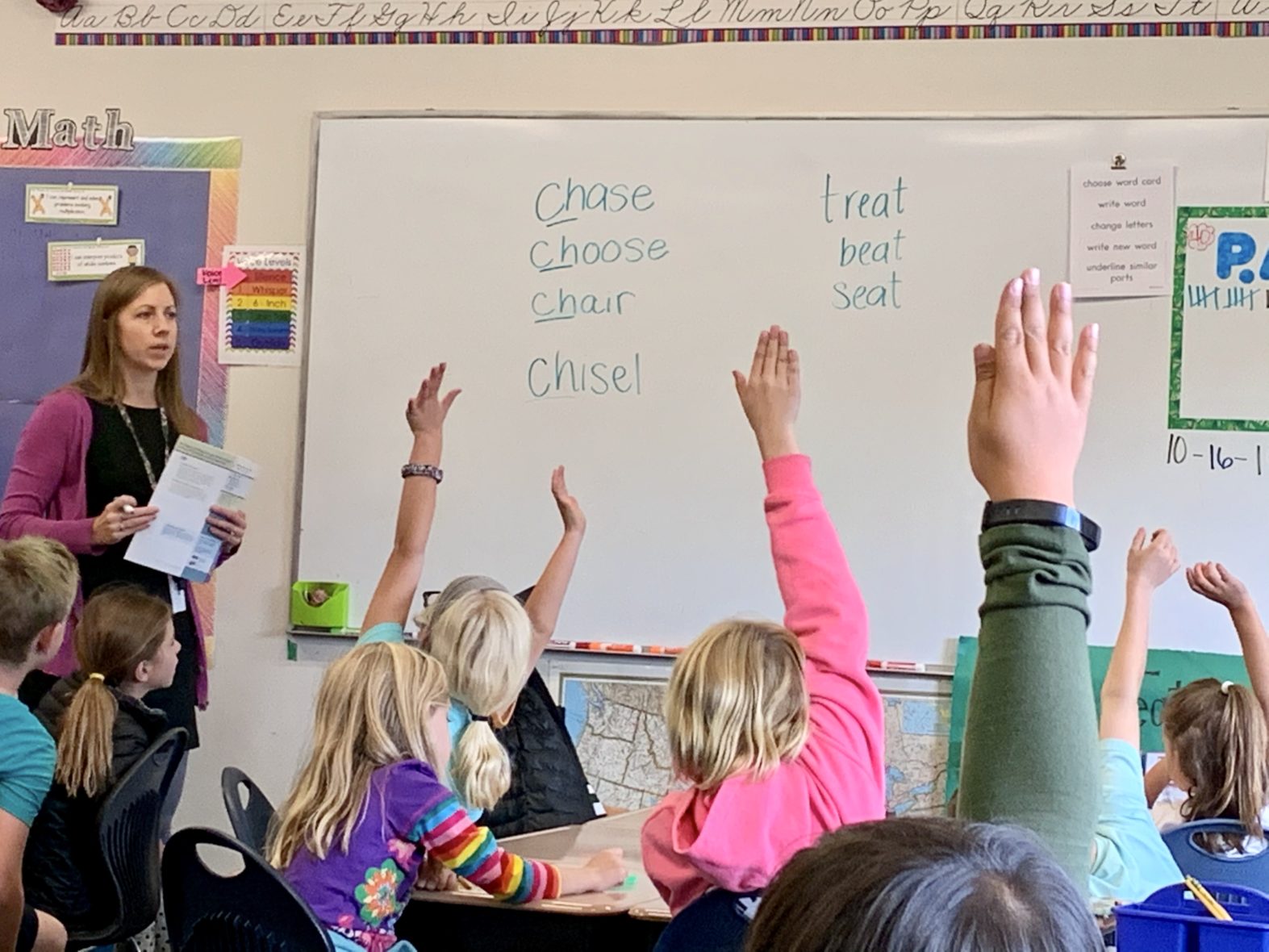

Little says he is comfortable with the way schools are spending the $26 million in literacy money. By design, schools have a “smorgasbord” of options, from hiring reading coaches and paraprofessionals to offering summer programs or all-day kindergarten. (Many schools have chosen to put the bulk of their money to hire additional staff.)

Ybarra folded $26 million for literacy into her budget request for next year. She thinks there is a good case to present to legislators — fall reading scores are up from a year ago, in first, second and third grade — but she knows it’s early. “We’re talking about giving kids time to show us the results and the gains.”

Before signing off on next year’s budget, one key legislator wants answers — from other state leaders, and from the Boise State University researchers who will deliver a followup report on the literacy program early next year.

“I want evidence that the money that the state has invested is helping Idaho kids read better,” said Rep. Wendy Horman, R-Idaho Falls, the vice chair of the budget-writing Joint Finance-Appropriations Committee.

Earlier this year, Horman played a key role in writing the K-12 budget that included the $26 million for literacy. The bill included $3 million in one-time money. That will be a talking point. In 2020, a tight budget year, Horman and her colleagues will have to decide whether they want to replace that $3 million, and figure out where it would come from.

Little: Taxpayers and patrons deserve accountability

Here’s a second question for 2020: Will Little push to hold schools accountable for their reading scores?

That’s one idea from his K-12 task force, “Our Kids, Idaho’s Future,” which spent five months drilling down to five recommendations based on Little’s two main education objectives: college and career-readiness and early literacy. The task force recommends using the IRI to grade schools and administrators. The yardstick would be student growth — comparing IRI scores over time, and comparing schools with similar demographics.

The idea of an accountability metric could have built-in appeal with legislators who want to see a return on their investment. And there doesn’t figure to be much cost attached to using an existing test as a school accountability metric.

Educators have mixed opinions.

The IRI, by nature, is designed to be a screener, helping teachers see what they need to do to help students improve. Using the IRI to assess schools could turn the test into a “gotcha” moment, said Keith Donahue, executive director of Sage International School, a Boise charter. “You run the risk of losing all that potential positivity.”

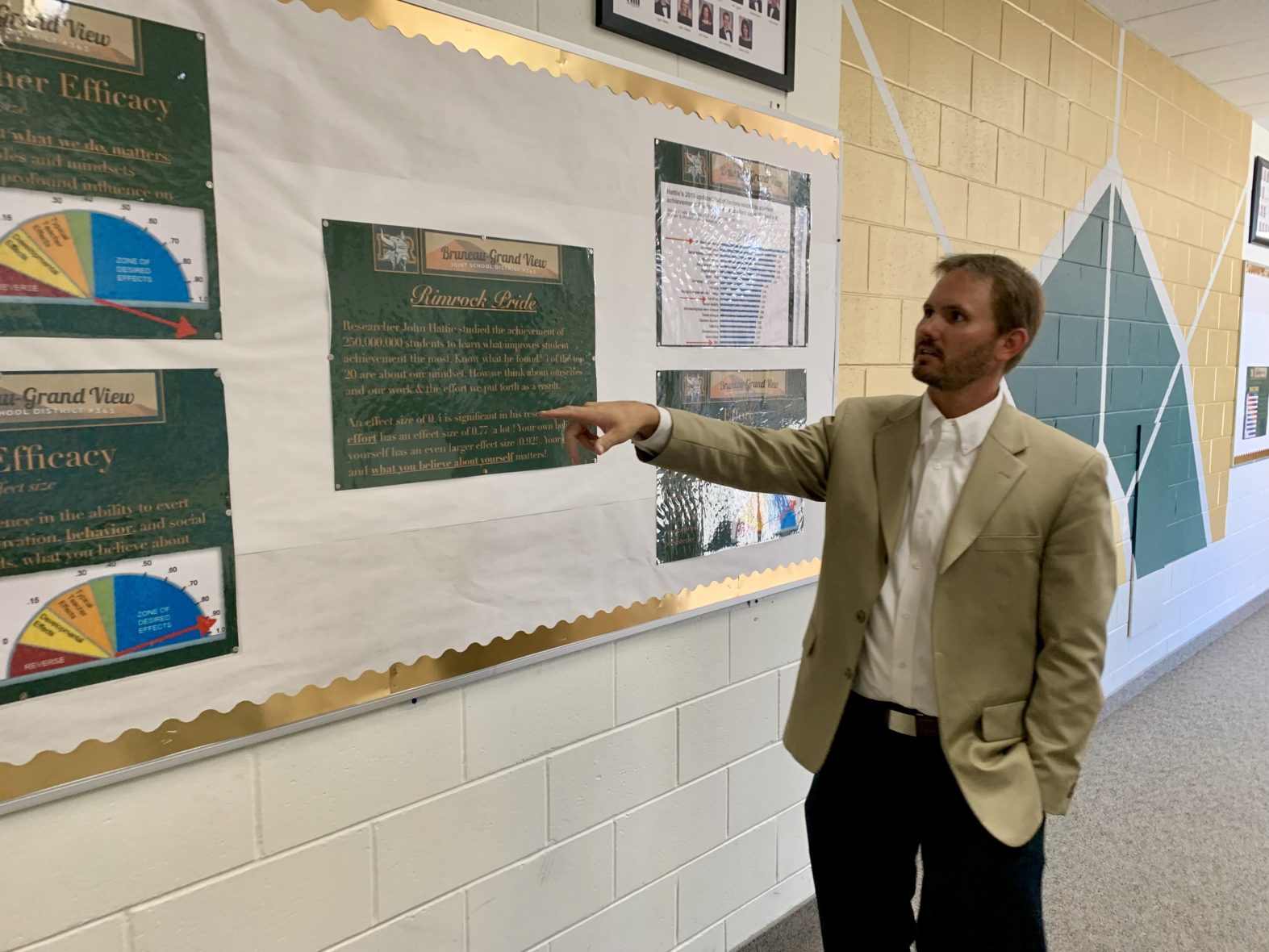

To Ryan Cantrell — the superintendent of the Bruneau-Grand View School District, and a member of one Little task force subcommittee — it all boils down to a simple question. If the IRI isn’t a fair yardstick, then what is?

“I would be just fine with it, but I wonder if I’m in the minority,” he said. “I have to own that data whether I like it or not.”

Little has signaled his support for the 26-member task force’s work in general, and seems particularly partial to the IRI accountability recommendation.

As far as Little is concerned, he says, accountability is the biggest obstacle to teaching kids to read. Parents and voters need a scorecard: a way to judge whether school leaders and elected trustees are getting the job done. The IRI can furnish that scorecard.

Will Little push for all-day kindergarten?

Here’s a third question for 2020 — one that could carry a heavy price tag.

The task force has recommended expanding optional all-day kindergarten.

At least 81 districts and 16 charter schools offer all-day kindergarten to at least some students, and some schools use their share of literacy money to finance these programs. Little says he’s “not at all shocked” to see schools using their money to hire additional kindergarten teachers — and after all, the literacy program is designed to give local schools a variety of options.

But lawmakers might not be ready to up the ante. Several Republican lawmakers on the task force either opposed the all-day kindergarten recommendation or abstained from voting, suggesting the proposal is already in jeopardy.

Horman voted against the recommendation. She doesn’t just want evidence that all-day kindergarten helps kids learn to read. She wants a dollar figure. She says she can only guess at the cost, based on the $52 million price tag the Idaho School Boards Association attached to a 2018 proposal.

“There were no cost estimates that were brought forward to the task force,” she said.

Task force co-chair Debbie Critchfield is mindful of the politics. The State Board of Education president knows legislators will want to see proof that a longer kindergarten day makes a difference. But she also doesn’t want to get out ahead of the issue.

“I’m going to wait to see what the governor is going to do,” she said.

Idaho’s reading challenge: This series at a glance

Day One

Reading realities: Idaho plays catchup

Following the dollars, defining success

Day Two

What’s working? School success stories

Idaho’s daunting demographic hurdles

Day Three

Testing kids, and seeking answers

Early education expands across Idaho

Day Four

Reading policy and reading politics