This is one of four stories featuring what some of the nation’s top-performing high-poverty schools are doing to boost achievement among students in poverty.

MURTAUGH — A decline in standardized math scores led to Murtaugh Middle School’s designation of “needing improvement” in 2010.

Superintendent Michele Capps credits the slump, and the State Department of Education’s response, for sparking a major turnaround in a high-poverty school district surrounded by a sea of southern Idaho farmland.

Murtaugh used a $500,000 state school improvement grant to add another math teacher and align math curriculum. The district also combined its elementary, middle and high schools into one 360-student school in order to bring benefits from added grant funding to kids in all grade levels.

“If we were going to get the money, we were going to make the most of it,” said Capps.

The 2010 grant has since dried up, but Murtaugh’s push to improve math instruction has grown. Today, Capps attributes the district’s soaring math scores not only to past changes but to teachers’ willingness to go all in on a state-sponsored professional development program aimed at improving math instruction.

Capps also credits the district’s decades-old preschool and all-day kindergarten for boosting achievement in reading and writing. In 2018, Murtaugh also outperformed its statewide peers — even though most of its students qualify for free and reduced-price meals, a measure of poverty.

“Our emphasis on early learning is huge,” Capps said.

What Murtaugh does differently

The 2008 Legislature approved the Idaho Math Initiative.

The statute was designed to boost lagging math scores through a range of state-funded programs and resources for school districts.

One of the programs, Idaho Regional Math Centers, plays a big part in the way Murtaugh teaches math.

Housed in the colleges of education at each of Idaho’s four-year colleges and universities, the centers provide schools across Idaho with experts and a range of resources, including on-site professional development.

For the past two years, Murtaugh’s K-12 teachers have participated in “lesson studies,” a model facilitated by math specialist Rhonda Birnie, who oversees the math center that serves Murtaugh and other schools in the area.

Murtaugh teachers meet with Birnie and other math teachers from across the region to create lesson plans targeted for improvement. Teachers then take turns teaching the lessons to their own students, with both their grade-level colleagues and Birnie monitoring student learning and development during the lesson.

After each lesson, the group “debriefs” about what went well and what didn’t. Feedback from the sessions drives the collaborative drafting of future lesson plans, and teachers repeat the process up to three times during a school year.

While Birnie helps teachers improve math instruction in all grades, Murtaugh’s preschool and all-day kindergarten teachers reinforce reading, writing and other basic skills.

Since 1997, Murtaugh has tapped into its general funds to make all-day kindergarten free for local families.

The preschool, which operates twice a week on federal migrant funds and what Capps called a “consortium of grants,” focuses on physical, social, emotional and basic reading and writing skills calculated to get kids ready for kindergarten.

Even though families pay $100 a year for preschool, Capps estimates that around 90 percent of the district’s students participate.

Murtaugh teacher Chelsea Egan works with both a full-time paraprofessional and a part-time paraprofessional and Title I teacher to teach the school’s sole kindergarten class.

How Murtaugh defies the odds

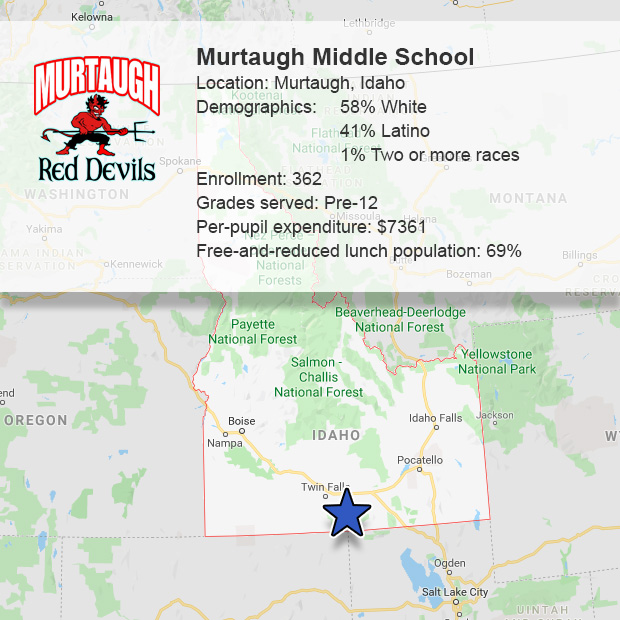

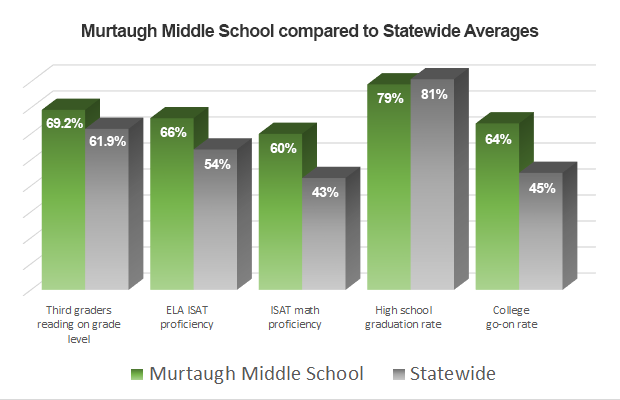

Murtaugh outperformed state averages on nearly all academic achievement indicators in 2018, despite the fact that 69 percent of the student population qualifies for free and reduced-price meals.

Here’s a breakdown:

Due to a low number of students who took the 2018 SAT, the state redacted Murtaugh’s math and evidence-based reading benchmark numbers.

What works

There’s “no comparison” between half-day and all-day kindergarten, Egan said, referencing the added instruction time offered in an all-day program.

That includes extra time with the Title I teacher and paraprofessionals who help in Egan’s classroom. Every school day, Egan’s full-time paraprofessional pulls each student out of class for one-on-one reading and to check for learning gaps.

“That’s a big help in a class with 36 students,” Egan said.

Preschool provides another boost for incoming kindergarteners. While Murtaugh’s preschool teachers expose youngsters to early reading and writing activities, they also reinforce the ins and outs of the classroom: listening to the teacher, sitting in a chair during lessons and forming lines when moving as a group.

These things might not seem like much, Egan said, but they allow kindergarten teachers to spend more time teaching and less time helping kids adapt socially when they arrive at the kindergarten door.

“I have no criers in my classroom this year because of preschool,” Egan said unequivocally.

Added instructional time, one-on-one sessions and a long-running preschool have long boosted reading and writing skills for Murtaugh’s students, Capps said, but more recent improvements in math stem from Birnie’s professional development model.

“(Birnie) really knows how to teach teachers,” Capps said. “I’ve seen major changes since we started working with her.”

Not all of those changes add up to increased math scores. Teachers’ openness to professional development has also improved, Capps said, because Birnie’s model is conducted largely by equals — teacher peers from other schools.

Birnie, the math expert, also poses “genuine” questions about student learning during lesson debriefings.

It’s “less intimidating,” Capps said, adding that teachers are seeing results because of it.

“(Teachers) always tell me after a session, ‘I want to do this again,’” Capps added.

Murtaugh isn’t the only school participating in Birnie’s lesson studies. Every Magic Valley school district participates to some degree, said SDE instructional support math coordinator Nicole Hall. Districts across the state participate in their respective math programs.

However, Murtaugh is a “level 3” participant, Hall said, which means that all teachers in all grade levels participate.

The district’s small size makes it easier to integrate best practices and improvements brought by Birnie’s program, Capps said.

“In that sense, it helps to be small,” she said.

What are the challenges?

Regional Math Centers represents a “huge commitment,” Capps said.

Study lessons alone require each math teacher to miss up to five school days during the year, heightening the need to find substitutes in the remote district.

The $100 required for preschool can also be tough for local families experiencing more severe poverty.

Still, Capps attributes the program’s longevity to the idea that it’s a worthwhile investment for locals.

“Families have been putting their kids in preschool here for a long time,” she said.